Ukrainian children transported to Russia range in age from toddlers to teens. In some cases, there was adoption, in others there were summer camp programs where the children were supposed to return home but never did.

London: In a week when Russia’s minister of foreign

Children are always the innocent victims in warfare. Western TV screens have recently been filled with images of youngsters being taught in schools around Ukraine, sometimes in cramped, dark basements, only to scamper to safety when the sirens warn of incoming Russian missiles. According to a United Nations report last January, thousands of schools, pre-schools and other educational facilities in Ukraine have been damaged or destroyed, due to the use of Russian explosive weapons. This has resulted in many parents and caregivers being reluctant to send children to school, fearing for their safety.

UNICEF, originally called the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund, now officially the United Nations Children’s Fund, responsible for providing humanitarian and developmental aid to children worldwide, believes that the war in Ukraine has currently disrupted education for more than five million boys and girls. While nearly two million children are accessing online learning opportunities, and 1.3 million children have enrolled in a combination of in-person and online learning, recent Russian attacks against Ukraine’s electricity and other energy infrastructure have caused widespread blackouts that have also affected education. As a result, almost every child in Ukraine has been left without sustained access to electricity, meaning that even attending virtual classes is an ongoing challenge.

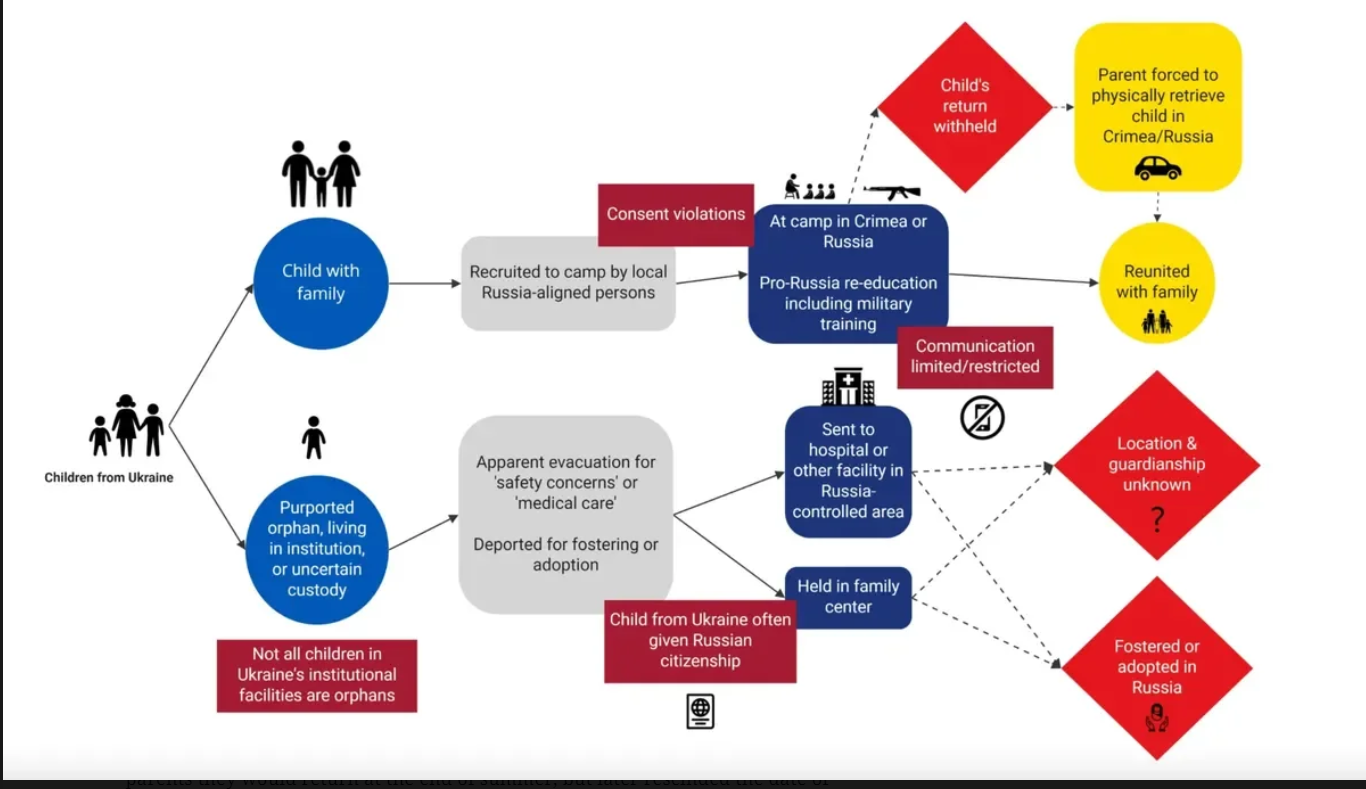

But there’s another, more sinister factor at play. Numerous accounts point to Russia’s federal government operating a large scale, systematic network of camps and other facilities that have held at least 6,000 children from Ukraine within Russian-occupied Crimea and mainland Russia during the past year. A Conflict Observatory report published last month claims that some forty-three facilities are carrying out “re-education” of Ukrainian children in an effort to make them more “pro-Russian” in their personal and political views. Eleven of the camps are said to be located more than 500 miles from Ukraine’s border with Russia, with two camps in Siberia and one in Russia’s far-eastern Pacific coast.

Ukrainian children transported to Russia range in age from toddlers to teens. In some cases, there was adoption, in others there were summer camp programs where the children were supposed to return home but never did. The report identifies the start date for transporting Ukrainian children to Russia as days before the full-scale invasion began on 24 February last year. The first group of children transported included 500 purported orphans “evacuated” by Russia from Donetsk Oblast. The reason given publicly at the time was the supposed threat of an offensive by Ukrainian forces. Some of those evacuated children were later adopted by Russian families.

The Ukrainian government and UN senior human rights officials have constantly raised the alarm over these activities since the early days of the war. This grew louder in May last year when President Putin issued a new decree that made it quick and easy to adopt Ukrainian children, which was next to impossible before the war. At the same time, the Kremlin announced that it would extend government support to Russian families who adopt Ukrainian children, with the biggest payment going to those who were handicapped.

Russia’s commissioner for children’s rights, Maria Lvova-Belova, heads the adoption operation for the Kremlin. Last summer she reported that some 350 orphans from the Donbas region were adopted by Russian families, while another 1,000 Ukrainian children were awaiting adoption across Russia. Claiming that Lvova-Belova was simply carrying out an operation to steal Ukrainian children, last September the US government added her name to the growing number of Russians who are on the sanctions list.

The Kremlin, however, insists that the transfer of children is a charitable effort to save them from the horrors of war and give them a better life than they had before. Ukrainian children, it says, are simply being evacuated from combat sites, attending “recreational camps, receiving medical evaluation, or as orphans are being adopted by loving Russian families”. As evidence, plane and trainloads of bewildered Ukrainian children can be seen paraded in propaganda videos and state TV programmes as they arrive in Russian towns. The youngsters are welcomed with gift baskets and tight hugs from adults they’ve never met in person before, prospective guardians eager to facilitate their integration into the new “motherland”. “You have to see how they have changed in just a couple of months—joyful, bright, smiling”, Lvova-Belova said at a naturalisation ceremony last July, when a group of Ukrainian children received their brand-new Russian passports. “Now that the children have become Russian citizens, temporary guardianship can become permanent”, she added.

But Ukrainian parents see it a different way. Those whose children were taken to the camps say they were pressurised to send their children on to Russia. Others insist that they did not give their consent for their children to be taken and were misled about their children’s return dates. Some were pressured to sign consent documents granting power of attorney where the name of an individual taking custody was left blank, leaving no way to trace where a child went after being taken. Others say they were denied the ability to retrieve their children, or otherwise denied contact and access to them.

Those mothers who have contacted their children say they were alarmed by what they learned. Inessa Vertash hadn’t seen her 15-year-old son, Vitaly, for five months. Attracted by the offer to go on a two-week trip to a camp in Russia last year “to escape the fighting” in the Donbas region, with the promise of food and shelter, Vitaly finally contacted his mother last week. He said that after the two weeks were up he was moved to another camp which he likened to a prison. Inessa told the Sunday Times that her son was crying when he called her to describe the harrowing conditions. “There were no sheets on the beds, they were made to wear tattered old clothes, given only food fit for pigs and beaten if they didn’t sing the Russian anthem”, she said. Even more alarmingly, Vitaly told his mother that Russian camp workers were forcing Ukrainian girls as young as 13 to have sex with them.

Governments around the world, international NGOs and the UN have all condemned Russia’s actions. The UN commissioner for refugees, Filippo Grandi, said last month that “in a situation of war, you cannot determine if children have families or guardianship. Therefore, until it is clarified, you cannot give them another nationality or have them adopted by another family. So that’s very clear, we’ve said, but I want to say it again, this is something that is happening in Russia and must not happen.”

Grandi’s words are unlikely to resonate in the Kremlin. After all, stealing children from Ukraine is rather useful when you are trying to slow down a growing demographic deficit.

John Dobson is a former British diplomat, who also worked in UK Prime Minister John Major’s office between 1995 and 1998. He is currently Visiting Fellow at the University of Plymouth.