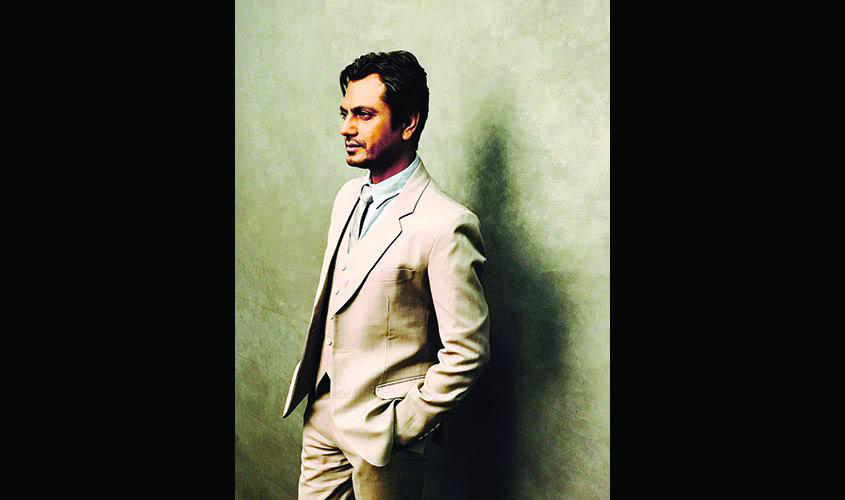

We are not told if it was actor Nawazuddin Siddiqui who lost his nerve or Random House, the publishers of his attempt at an autobiography. Whatever, his book, An Ordinary Life, has been pulled out from bookstores because of the actor’s “Kiss & Tell” approach to some of the women in his life. Not that the publishers can be entirely blamed. Laws in India are more sweeping in their scope than those of other major democracies, thereby making it difficult to evade legal action initiated by anyone either aggrieved or professing to be. Already, a Delhi lawyer has sought to prosecute the romantically active actor on a medley of charges, including—horror of horrors—adultery. This columnist had believed that only the husband was entitled to seek legal recompense in cases of adultery, but it would seem that such a charge can be flung even by an individual whose wife is not the object of the litigation. Add to this the ease of initiating litigation in India. The judicial system, especially once Chief Justice Verma, a quarter-century ago, insulated the institution from both the legislature as well as the executive, has few obvious limits to its discretion and scope. It is therefore clear that Niharika Singh and Sunita Rajwar (who at one time were apparently close friends of the actor from Budhana) have each the ability in our system to tie both Siddiqui as well as Random House in litigation that may go on for decades, India is of course a country where lawyers bequeath cases to more than one generation of their successors before the matter gets disposed of. Near-permanent stays and multiple (and lengthy) adjournments are a staple of litigation in India, where time gets calculated by “yugas”, each spanning several millions of years, so that a delay of several decades in the final disposal of a case is but a millisecond in such a universe. Surprisingly, in other countries, such an attitude to time is frowned upon, which is why so many foreign investors insist on outside adjudication for any dispute. Of course, as Cyrus Mistry demonstrated while he was in charge of the Tata group, even the condition of outside arbitration in a contract need not stand in the way of the matter being heard (and heard and heard and heard) in an Indian court. This means that the party taking recourse to the domestic judicial system can refuse to abide by outside arbitration until this be adjudicated through the elaborate and multi-layered Indian court process, often up to the level of a Division Bench of the Supreme Court of India.

We are not told if it was actor Nawazuddin Siddiqui who lost his nerve or Random House, the publishers of his attempt at an autobiography. Whatever, his book, An Ordinary Life, has been pulled out from bookstores because of the actor’s “Kiss & Tell” approach to some of the women in his life. Not that the publishers can be entirely blamed. Laws in India are more sweeping in their scope than those of other major democracies, thereby making it difficult to evade legal action initiated by anyone either aggrieved or professing to be. Already, a Delhi lawyer has sought to prosecute the romantically active actor on a medley of charges, including—horror of horrors—adultery. This columnist had believed that only the husband was entitled to seek legal recompense in cases of adultery, but it would seem that such a charge can be flung even by an individual whose wife is not the object of the litigation. Add to this the ease of initiating litigation in India. The judicial system, especially once Chief Justice Verma, a quarter-century ago, insulated the institution from both the legislature as well as the executive, has few obvious limits to its discretion and scope. It is therefore clear that Niharika Singh and Sunita Rajwar (who at one time were apparently close friends of the actor from Budhana) have each the ability in our system to tie both Siddiqui as well as Random House in litigation that may go on for decades, India is of course a country where lawyers bequeath cases to more than one generation of their successors before the matter gets disposed of. Near-permanent stays and multiple (and lengthy) adjournments are a staple of litigation in India, where time gets calculated by “yugas”, each spanning several millions of years, so that a delay of several decades in the final disposal of a case is but a millisecond in such a universe. Surprisingly, in other countries, such an attitude to time is frowned upon, which is why so many foreign investors insist on outside adjudication for any dispute. Of course, as Cyrus Mistry demonstrated while he was in charge of the Tata group, even the condition of outside arbitration in a contract need not stand in the way of the matter being heard (and heard and heard and heard) in an Indian court. This means that the party taking recourse to the domestic judicial system can refuse to abide by outside arbitration until this be adjudicated through the elaborate and multi-layered Indian court process, often up to the level of a Division Bench of the Supreme Court of India.India’s Canutes are seeking to stifle expression they deem inconvenient,

King Canute sought to roll the waves of the sea back, and expectedly failed. In similar fashion, through court verdicts and through other means, India’s Canutes are seeking to stifle verbal, cinematic and written expression that they deem inconvenient, unaware that technology is leaping ahead in such a fashion that transparency will soon become inevitable. Unless it be decreed someday that India and its citizens be barred from the internet, a disruptive mode of communication and information dissemination that is constantly fighting back against efforts at control. Should some individual download Siddiqui’s efforts at literature online, it would become accessible to millions within an instant. And if this person is (according to the internet protocol used) operating from Belarus or Panama, rather than from the hyper-regulated territory that comprises the Union of India, getting judicial recourse against him or her would be close to impossible. Both Random House as well as Siddiqui would lose out on the royalties they would have earned, had their nerve held and both the actor and his publisher been ready to face up to the hectoring of television anchors eager for their “villain of the day” in the nightly gladiatorial contests that talk shows are in India. And, of course, face up also to the possibility of jail time, perhaps courtesy a Delhi lawyer, who has made it his mission to go after the actor. But by consigning the book to “raddi”, the lens of public attention has been focused much more strongly on the two ladies aggrieved by Siddiqui’s absence of discretion. Their experiences with him have become public knowledge in a way far more potent than would have been the case had the book come out and within weeks, faded from sight. Coming from a family which includes Aubrey Menen (the author of what was the first book banned in free India), this columnist has refused to take recourse to the law even when the most toxic of calumnies were said and written about

In a society less Victorian than our own, the two ladies who figure prominently in An Ordinary Life, would have written their own versions of what took place between themselves and the actor, who has now garnered so much attention as a consequence of his book being scrapped. Will it now go online? Will a publisher outside India print perhaps a racier version, now that his pursuers have ruffled actor Siddiqui by their moves? If sold outside India, copies in plenty will find their way back to our country. The response seen to the Siddiqui book illustrates the Victorian attitude, which is “Do what you like, but don’t get found out”. Unfortunately for the bashful, in these days of mobile phones doubling as cameras and recorders, keeping such secrets secret is becoming an impossible errand.