Early on February 18th, communities in Zambia’s Copperbelt Province confronted an environmental catastrophe that shattered their economic security overnight. A massive failure at Sino-Metals Leach Zambia, a mine operated by China Nonferrous Metals Industry Group, released around 50 million litres of toxic acidic waste into the Mwambashi River. The spill swiftly poisoned vital water sources, wiped out fish and wildlife populations, and destroyed vast areas of agricultural land, severely impacting local livelihoods and ecological health.

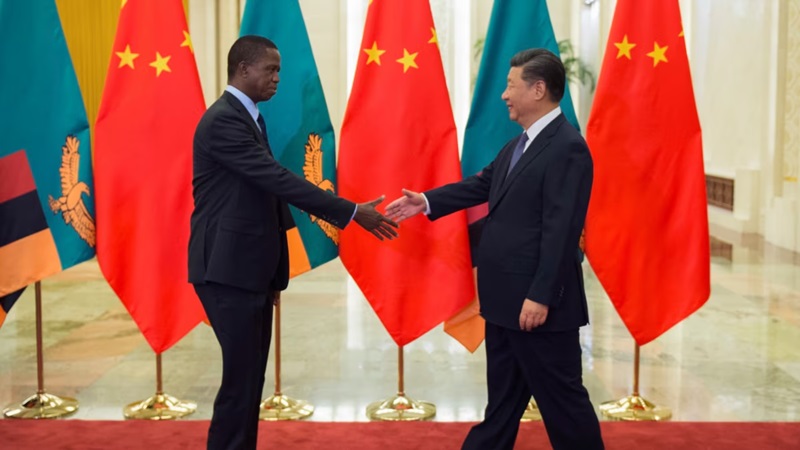

The Chambishi disaster has cast a stark spotlight on the deeper vulnerabilities facing Zambia—economic dependency on Chinese investments coupled with crippling debt obligations. Zambia owes more than $4 billion to China, making it one of Africa’s most indebted nations to Beijing. Much of this debt emerged from ambitious infrastructure and mining projects aimed at revitalizing Zambia’s economy, largely financed by Chinese loans. However, the very loans that were meant to boost Zambia’s economic independence now limit its ability to regulate the activities of its major creditors.

Zambia is Africa’s second-largest copper producer and plans to more than triple its copper output by 2033, relying significantly on Chinese capital to achieve this ambitious goal. Over the past two decades, Chinese firms have invested more than $3.5 billion into Zambia’s copper mines, creating about 15,000 jobs but also cultivating substantial leverage over the country’s economic and political decisions. This dependence has fostered regulatory complacency, allowing companies like Sino-Metals to operate with minimal oversight, frequently ignoring environmental safeguards and labour standards.

Chinese firms in Zambia have a troubled history. Sino-Metals operates within the Zambia-China Economic and Trade Cooperation Zone—the continent’s first Chinese-funded special economic zone offering tax incentives and streamlined regulatory approvals. Critics argue that such preferential treatment weakens the country’s regulatory framework. Just days after the Chambishi spill, another smaller spill at a Chinese-owned mine resulted in a worker’s death after the company reportedly attempted to hide the incident. These episodes highlight a pattern of negligence, exacerbated by Zambia’s reluctance to enforce strict penalties against Chinese firms for fear of jeopardising crucial financial relationships.

Zambia’s complex debt restructuring negotiations illustrate China’s strategic influence. In 2023, Zambia reached a preliminary agreement to restructure $6.3 billion of its external debt, of which $4.1 billion was owed to Chinese lenders. Yet shortly after, China contested the terms previously agreed upon, leading to prolonged negotiations that dragged on until mid-2024. This lengthy restructuring process underscores Zambia’s vulnerability to Chinese economic diplomacy—where debt becomes a tool for influencing national policy and regulatory decisions.

Experts warn that Zambia’s economic ambitions carry inherent risks, emphasizing that inadequate waste management practices at current production levels could inevitably lead to further environmental disasters. Such incidents fuel perceptions of neo-colonialism, reinforcing local resentment toward China’s economic practices.

The political ramifications are significant for President Hakainde Hichilema, who came into office promising transparency and accountability. With strong voter support in urban areas, including the economically crucial Copperbelt, the president now faces pressure to balance the economic benefits of Chinese investment against growing public demands for accountability and environmental protection. His administration has suspended Sino-Metals’ licence pending investigation, promising tougher enforcement. But past inconsistencies in holding companies accountable have left communities sceptical.

Zambia’s experience is not isolated. Chinese mining firms operating in Zimbabwe and Cameroon have similarly faced accusations of severe environmental damage, worker abuses, and disregard for local laws. Across Africa, China’s economic footprint is often accompanied by weakened environmental governance, raising questions about Beijing’s role as a sustainable development partner.

For Zambia, addressing this intertwined environmental and economic crisis will require profound policy shifts. Recommendations include diversifying foreign investments, reinforcing regulatory frameworks, and ensuring environmental and labour standards are enforced without compromise. Zambia’s recent tragedy could be a pivotal turning point—prompting a reconsideration of the costs of debt-driven growth

As Musongole and thousands like her grapple with their uncertain futures, Zambia stands at a crossroads. Navigating the difficult path ahead will determine not just the country’s economic prosperity but also its ecological integrity and national sovereignty. Breaking the cycle of debt and ecological destruction is not merely advisable—it has become existential.

Aritra Banerjee is a defence & security analyst.