ISIS has exploited the socio-political environment and young adults’ obsession with technology.

Cyberspace is the ideal platform for terrorists because, unlike conventional warfare, barriers to entry into cyberspace are much lower—the price of entry is an Internet connection. The surreptitious use of the Internet to advance terrorist group objectives has created a new brand of Holy War—“Virtual Jihad”—which gains thousands of new adherents each day. For terrorist organisations, a clear benefit of cyberspace is its ability to readily radicalise individuals from a distance and at any time, utilising the Internet and superior social media intelligence to gain attention and remain relevant globally.

Cyberspace offers potential jihadists the opportunity to receive instruction and training on topics ranging from data mining to psychological warfare. The use of the Dark Web and encryption programs allow terrorist groups to effectively communicate in secret. Although terrorist organisations have been adept at utilising the Internet to spread propaganda and provide instructions for attacks, their ability to launch offensive attacks via computer networks had previously been limited. Cyberattacks attributed to terrorists have largely consisted of unsophisticated tactics such as e-mail bombings of ideological foes, DDoS attacks, or defacing of websites. Even when such attacks have been successfully deployed, the damage inflicted has been limited, largely because global intelligence agencies actively monitor their websites, conduct analyses to determine potential terrorist plots, and render some of the domains inaccessible to the public. That has now changed.

A VIRTUAL CALIPHATE

Long after the current collection of terrorist groups have ceased to be a major threat from a physical perspective, they will remain omnipresent in cyberspace, promoting a virtual caliphate from their safe haven behind computer keyboards around the world. Islamic extremists are natural candidates to transition to the virtual world because it offers them automatic citizenship beyond the nation-state. Decades of violent conflict, border disputes, and shifting refugee populations have left millions of Muslims without a clear national identity—a virtual caliphate offers refuge, free from terrestrial constraints, which can be accessed from anywhere in the world.

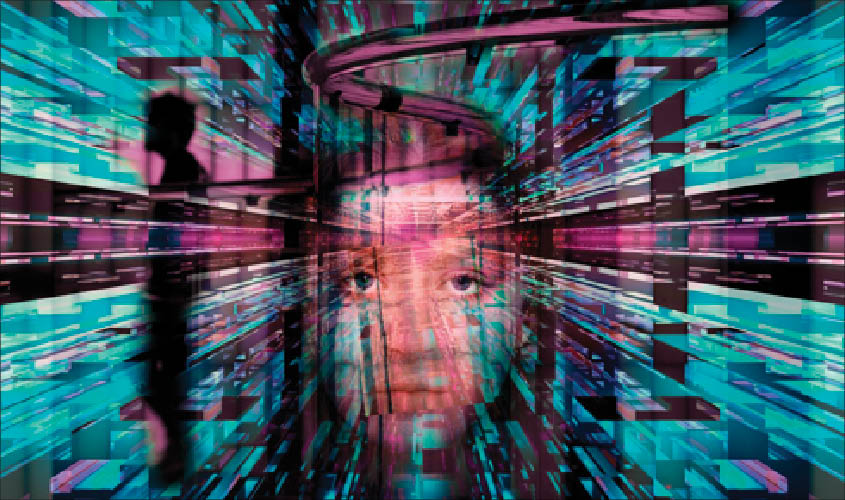

Since the Islamic State (ISIS) was founded, its leaders have deftly and continually rewritten the narrative by which they could claim that the group’s desired caliphate exists, where it is located, and who its adherents are. Unconstrained by the absence of a definitive Quranic guideline for what constitutes a caliphate, the ISIS created its own self-promoting doctrine. The group expanded its caliphate narrative to include a wide range of options for participation: membership included everyone from the passive observer reading a blog or curiously following a Twitter feed, to the keyboard jihadist editing Rumiyah or hacking a website, to the real-world operators attacking a nightclub or running down holiday celebrants with a delivery truck. The ISIS has successfully exploited the socio-political environment and young adults’ obsession with technology to establish a growing community of devotees in the ungoverned territory of cyberspace, ensuring its ability to continue to coordinate and inspire violence well into the future.

This notion of a virtual caliphate clashes with traditional notions of statehood and governance, but it is not the first attempt that has been made to create a virtual state. In 2014, Estonia took the unprecedented step of offering any person in the world a chance to become an Estonian “e-resident”, in an attempt to create a “digital nation” for global citizens by offering to provide government-issued digital identification to anyone in the world, and enable non-Estonians access to Estonian services such as company formation, banking, payment processing, and taxation. Doing so would allow Estonia to continue operating as a state even if its physical territory were ever seized. By harnessing the millions of people who form its social network, the ISIS expanded its community of e-citizens to promulgate its radical ideology and direct attacks across the globe well before the collapse of its physical caliphate.

The ISIS has also capitalised on the world’s evolving propensity to integrate online activities with real world activities. Social media has had an incredible multiplying effect on radical messaging, and the ISIS has had great success publishing online, which has resonated particularly well with disenfranchised Wahhabi and youths, inspiring some to act on inspiration and guidance received online. The ISIS has exploited their search for meaningful identity by promising to restore their dignity and might so that they may find personal fulfilment and purpose.

The virtual world is in some ways more compelling than the real world, because storylines can be artfully crafted to be maximally appealing, while omitting anything that may be perceived of as negative. A promise is much easier to make online, as is the vision of fulfilling aspirations. The ISIS has created virtual messaging that is wildly at odds with the reality of life as an ISIS fighter on the ground. Cyberspace has enabled the ISIS to turn tactical defeats on the battlefield into glorious martyrdom operations that highlight the bravery and commitment of its fighters. The loss of territory and the deaths of key leaders have served to feed propaganda efforts that are used to prove the resiliency of the caliphate.

In the face of the force-multiplying impact of the ISIS’ adaptive narrative, even concerted efforts by Muslim clerics have largely failed to undermine ISIS’ caliphate narrative. While the vast majority of the world’s estimated 1.6 billion Muslims are not ISIS supporters (perhaps just a fraction of 1%, although no one can say for certain), the group’s ability to engage virtually with large swathes of this population drives varying degrees of participation in the virtual caliphate, including non-supporters, passive observers, benign fans, “keyboard jihadists”, and real-world actors. This diverse range of participants helps to ensure that the notion of a virtual caliphate will endure long after the current crop of ISIS leaders is gone. The ISIS has found its own salvation via the Internet, particularly since it has already passed the peak of its real-world power.

Daniel Wagner is the CEO of Country Risk Solutions and author of the book Virtual Terror.