Rasheed devotes a chapter to each of the Scindias, bringing out the challenges the women had to face, for they had a much more challenging task than the men to find their place in the political arena.

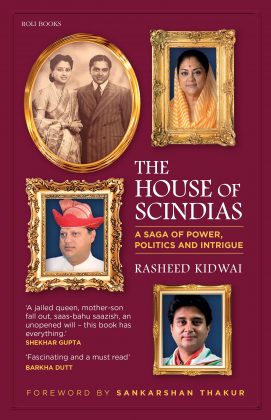

Political historian Rasheed Kidwai is out with his latest book, The House of Scindias, which takes a look at one of India’s most intriguing political dynasties. The timing is interesting because the book comes out at a time when the entire family is united on one political platform—perhaps for the first time if we exclude Madhavrao Scindia’s initial plunge into politics when he contested his first elections from Guna as a Jan Sangh nominee. Of course, he won. For a long while, during both Rajmata Vijayaraje’s time and later even during Madhavrao’s tenure it was a given that Gwalior-Guna region would elect a Scindia. The constituency of Gwalior chose Madhavrao over a stalwart like A.B. Vajpayee once (1984), if you will recall. It is only the current generation that has frittered away this goodwill, with Jyotiraditya Scindia losing the Guna seat in the 2019 elections to a former associate of his, Krishna Pal Yadav who contested on the BJP ticket.

Perhaps it was the shock of his first ever electoral defeat that made him switch over to the BJP. Perhaps it was his disillusionment with the Kamal Nath-led Congress government in Madhya Pradesh. But Kidwai adds all these to a larger disillusionment with the Congress leadership, especially Rahul Gandhi. As he writes in his book, “The defeat (in Guna) created a deep wedge between Jyotiraditya and the Gandhis as he could not reconcile to his electoral defeat.” Kidwai also points out that in a way Scindia blamed the Gandhis for this loss as he was reportedly not keen to contest the 2019 election, as he had been made Congress general secretary in charge of Uttar Pradesh at the time and spent most of his time working there, along with Priyanka Gandhi Vadra, for both were given charge of the state. This is something I can also add to, for I happened to meet Jyotiraditya during the 2019 Lok Sabha polls and he was spending most of his time in Uttar Pradesh, instead of focusing on his own constituency. And whatever may be said, the Congress was up against the formidable Narendra Modi, so every opposition candidate was glued to his or her constituency. Unlike Jyotiraditya, Priyanka Gandhi Vadra was not contesting an election and so could afford to focus all her energies, and time, in Uttar Pradesh. Jyotiraditya did not have that luxury and paid the price.

However, Kidwai points out that the disillusionment with the Gandhis was brewing for some time. “Some Congressmen think that the seeds of discord between Jyotiraditya and the Gandhis date back to UPA 1 when the younger lot of MPs were not made ministers despite then PM Manmohan Singh eagerness to induct fresh blood. In 2014 the year the Congress lost power at the centre, Jyotiraditya was not made party leader in the Lok Sabha. Instead the job went to a listless Mallikarjun Kharge with Captain Amarinder Singh as his deputy.” And Kidwai adds that in 2017 when Captain Amarinder went off to Punjab as CM, the post was kept vacant “despite Scindia’s legitimate and obvious claim”. This is a valid grouse for many young MPs, who debuted along with Rahul Gandhi, as the Class of 2004 were kept on ice when the party was in power simply because their more powerful colleague was not “ready” to take ministerial office and they could not be promoted before him. This is unlike the BJP that saw Prime Minister Modi induct his own team of Gen Next leaders along with him when he assumed office (as the cost of the older lot from Vajpayee’s BJP). And now in his second term, the novices of his first term have been groomed to hold key ministries—such as Amit Shah, Nirmala Sitharaman, Piyush Goyal, Dharmendra Pradhan and even a Smriti Irani.

Kidwai, who has also authored Bollywood Netas and 24 Akbar Road comments that the fallout between Scindia and the Gandhis was not unlike the fallout between the Bachchans and the Gandhis. Like the Bachchans the Scindias too (at least Madhavrao and his son) enjoyed a personal rapport with Rajiv, Sonia and later, Rahul and Priyanka. As Kidwai writes, “Just as the real cause of the split between the Bachchans and the Gandhis remains in the realm of speculation…the real reasons for Jyotiraditya’s devastating goodbye has not come out in the public domain as yet.” But Kidwai does quote from M.L. Fotedar’s autobiography, The Chinar Leaves, where the veteran leader recalls being summoned by Indira Gandhi a few days before her assassination, along with Rajiv Gandhi and Arun Nehru. In his book, Fotedar claims that Indira Gandhi warned her son, “Do not bring Teji’s son—Amitabh—into electoral politics and do not induct Madhavrao into your cabinet if ever you become Prime Minister.” This passage is quoted by Kidwai and it’s interesting to see it in the context of Jyotiraditya’s break with the Gandhis. Certainly, Jyotiraditya’s peeve at being consistently left out, eventually led to a Made-In-Scindia crisis that cost the Congress its government in Madhya Pradesh.

Rasheed devotes a chapter to each of the Scindias, bringing out the challenges the women had to face as well, for they certainly had a much more challenging task than the men to find their place in the political arena. The feisty Vasundhara Raje managed to make a mark in another state where she did not have the Scindia goodwill as a cushion and it is to her credit that she still holds her own in Rajasthan despite getting little support from the Centre. The irrepressible Yashodhara Raje too has been fighting her own battles in Madhya Pradesh, where again she got none of the credit but all the downside of being an ex-royal in the carefully cultivated plebian world of the BJP. What is interesting is that most of the brickbats that came her way were from her rivals within the BJP. Perhaps they were wary that a Scindia would not remain in the sidelines for long.

Kidwai is certainly the master of the anecdote and there are many nuggets that pepper his analysis, making the narration as accessible as an engaging conversation. Plus his political insights into both the workings of the Congress and the BJP, as well as his understanding of the state’s politics (Kidwai himself is from Madhya Pradesh) make this a fascinating insider’s account. Well, as inside as the Scindias would allow an outsider to get, for don’t forget when asked by a journalist whether she had any role in bringing her nephew over to the BJP, Yashodhara’s reply was simple but to the point: “I’m not going to let you in on whether I had a role or not. Sorry.”