The book explains why Chatterjee looked into details which were masterful. No wonder he was a sentimental filmmaker, as every real filmmaker should be.

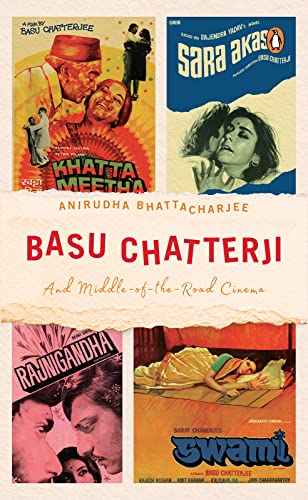

In page 15 of his book, Basu Chatterjee and Middle of the Road Cinema, author Aniruddha Bhattacharjee talks about Teesri Kasam, a 1969 Raj Kapoor-Waheeda Rehman starrer, and how Chatterjee was somewhat disappointed that the films he was associated with did not work.

And then one day, he was introduced to his namesake Basu Bhattacharya. Chatterjee worked as an assistant director for the movie.

The book, published by Vintage/Penguin Random House, explains why Shailendra, who sunk a lot of cash into Teesri Kasam, passed away after the release of the movie. Chatterjee is quoted in the book saying, “I always felt that the making of Teesri Kasam was partly responsible for his death. He had invested a lot of money, consequent to which he would worry about how to pay his creditors, and had started drinking heavily, something which proved fatal.”

Chatterjee assisted director Govind Saraiya when the latter made Saraswati Chandra in 1968. In both Teesri Kasam and Saraswati Chandra, Chatterjee excelled in introduction scenes and worked well on imagery. Both movies had beautiful pieces of music, absolutely incredible. There was a dynamism and physicality in both movies.

The author, who spent many memorable moments with the director, explains how Chatterjee got the book, Sara Akash, from his friend Arun Kaul and eventually bought the rights to the book from Rajendra Yadav for Rs 21. Rakesh Pandey, who grew up in Nahan – now home to a lion safari – and trained at the National School of Drama (NSD), was the hero of Sara Akash. He was recommended to Chatterjee by none other than Mrinal Sen. The female lead was Madhuchanda Chakrabarty, daughter of actress Madhuri Chakrabarty. Madhuchanda’s claim to fame was her dubbing for Tanuja in Uttam Kumar starrer, Deya Neya. When she walked into the dubbing studio, Uttam Kumar was surprised to see the South Point student in her school dress.

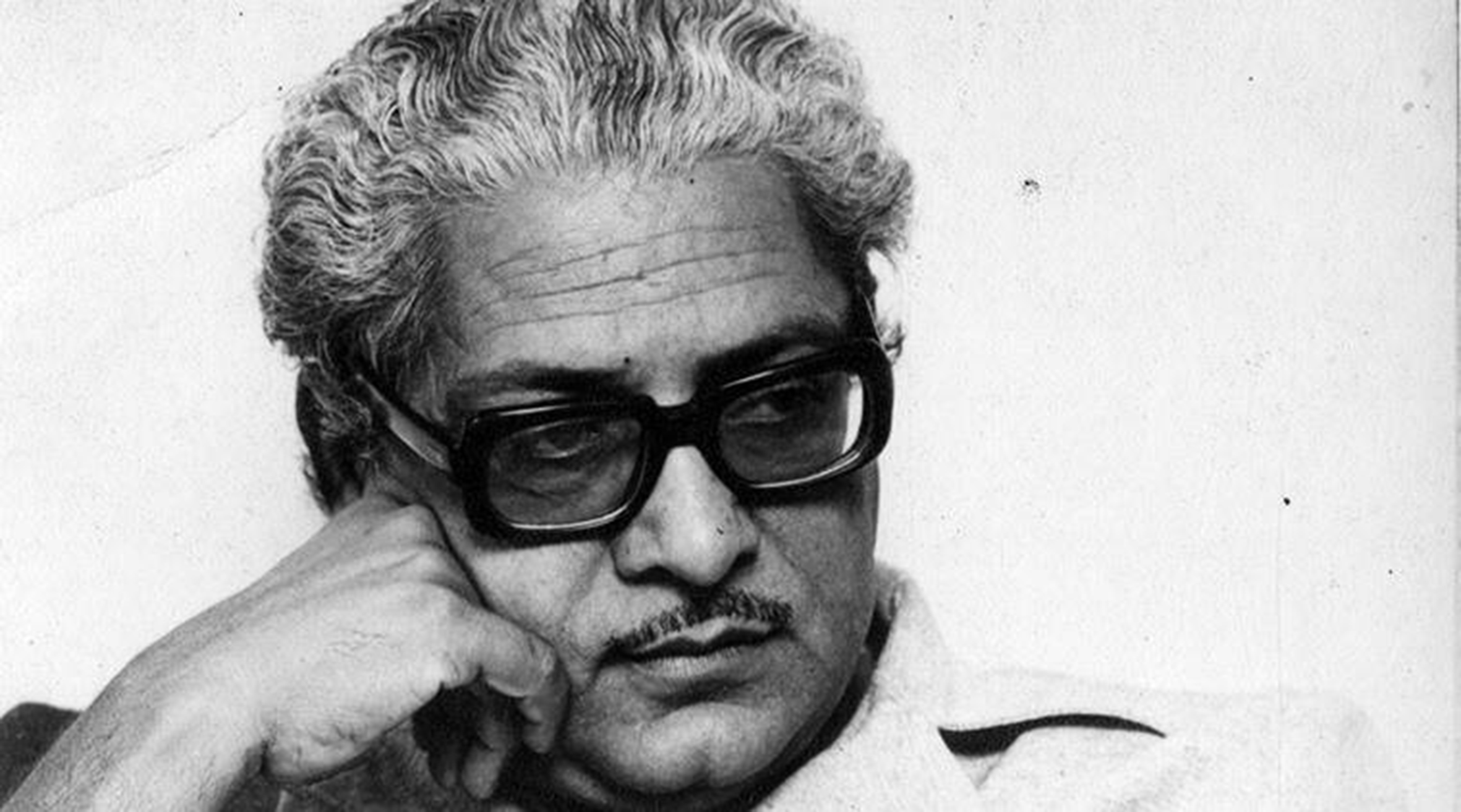

The author explains the dynamism and physicality in Chatterjee’s films that worked wonders for the director. Chatterjee, who started as a cartoonist in Russi Karanjia’s Blitz before shifting to films, was a great visual artist. He made movies that were not just about his thinking but actually about the doing. Chatterjee always thought about how to do his best in the moment. The author makes it clear that Chatterjee is a filmmaker rather than a director.

I read some brilliant lines by Bhattacharjee, the author. And it actually sums up Chatterjee: “Bombay was back in the centre of things in the 1970s, coinciding with the birth of the Angry Young Man. But Basu Chatterjee’s Bombay wasn’t about the descent of the young man into crime and turning super-rich. It charted the journey of persistent people and families who took one step a day to improve upon yesterday’s baseline.” Chatterjee was a master of memorable scenes, too many to mention – all brilliant and cinematic. The book vividly details how he directed Piya Ka Ghar with Anil Dhawan and Jaya Bhadhuri. The movie, released in 1972, was a remake of Raja Thakur’s Marathi film, Mumbaicha Jawai. It portrayed the difficulties of life in India’s biggest city during the 1970s. I remember Kishore Kumar’s haunting song, Yeh Jeevan Hai. It was Kumar’s first song for Chatterjee. The book explains, in as many words, Chatterjee’s incredible intelligence that he displayed throughout his career. I remember the last scene from Piya Ka Ghar where the couple decides to stay back in the chawl and seek fresh love. I also recall how the song, Phool Tumhe Bheja Hai Khat Mein, was picturized for Saraswati Chandra and Chalat Musafir Le Liya Re for Teesri Kasam. Chatterjee was an assistant director for both films, but his contribution was immense. The moments of two lovers singing a song in two different locations (Saraswati Chandra) and the mood of a village fair frequented by the rich and poor alike (Teesri Kasam) are unbeatable and amazing, and you fall in love throughout the entire movie.

Bhattacharjee wrote about Chatterjee’s thoughts on the Angry Young Man (was it Amitabh Bachchan or Vinod Khanna?) and vividly explained Chatterjee’s concept of the common man. He writes, “In his films, Basu Chatterjee allowed for the possibility of a woman falling in love more than once. The story, devoid of melodrama, would be humorous, entertaining the public even while doing away with the overt sentimentalism, inane action-packed fights, and the mandatory six-song routine that were a staple template followed by most of the movies of that time (and now). These light entertainers, with a deeper sub-text, were recognized as a new genre and christened as middle of the road cinema.”

The other storyline I would like to discuss here is that of Rajnigandha, a movie that helped Chatterjee discover Amol Palekar after Amitabh Bachchan and Shashi Kapoor moved away. Amol Palekar, who worked in a bank and acted in Marathi movies, filled the slot and stayed with Chatterjee forever (doesn’t it sound like Soumitra Chatterjee’s association with Satyajit Ray?). After reading Bhattacharjee’s book, I get the feeling that Palekar was born for the age of innocence. He was smart, young, and always ready to fall in love but not necessarily win the girl. Palekar read Chatterjee’s script and was immensely impressed. In an interview, he said, “I kept wondering how someone who was so ill at ease narrating a story could write a screenplay in so much detail. Even the dialogues were there. He (Chatterjee) was extremely eloquent in the cinematic language.” Two months and Rs 7,00,000 later, Rajnigandha was complete.

The book explains why Chatterjee looked into details which were masterful. No wonder he was a sentimental filmmaker – as every real filmmaker should be. He explored humankind in style, and what comes with that, including pain, depression, and pure innocence. It is beautiful and unmatched. Only a humanist thinks deeply about human nature.

Traditional, good-intentioned, inter-family banter – claims the author – helped Chatterjee create the miracle of his films, and enhanced its values. Bhattacharjee feels Chatterjee’s movies can easily be counted among the richest and most emotionally produced works in Bollywood. The author explains why Chatterjee’s films created some fleeting madness and left some cultural footprints. He knew how to make his films successful.

Bhattacharjee is not just a film critic or a Bollywood reporter, he is the ultimate insider who blends his words with those who also had access to the actors, script writers, producers and directors. He is an award-winning author. Bollywood has always amazed India, everyone wants to have an extra slice of information if they are reading books on top actors and directors.

Some writers pen tomes for academic exercise