Planned by NGOs, Rahul’s pedestrian padyatra will avoid poll-bound Gujarat, HP.

Alleging that decisions in Congress are taken not by the party’s interim chief, Sonia Gandhi, but by Rahul Gandhi’s “proxies” who include his personal staff and security officer, Ghulam Nabi Azad has yanked his ties with the party he served diligently for the past five decades. Like Amarinder Singh in Punjab and many other leaders who quit the GOP to form their own regional outfits, he is slated to enter the ring in J&K where elections are on anvil. (Amarinder was chagrined after Rahul’s security officer, Byju, a former SPG man, was used as an emissary to convey political diktats.) At a time when the Congress Working Committee (CWC) is holding a virtual meeting on Sunday, 28 August, to decide on the question of party president and Rahul Gandhi, in tandem with NGOs, inspired by the likes of Yogendra Yadav, is embarking on a “Bharat Jodo Yatra”, the veteran leader has diagnosed what ails the GOP and quit the theatre. Congress’ official reaction ranged from wordsmith Jairam Ramesh’s jab, which drew on Azad’s initials: “GNA’s DNA has been Modi-fied” to Ashok Gehlot describing it as “childish”. The Gandhi troika, which has gone abroad, has not commented till the time of writing, though Rahul Gandhi’s tweets from abroad on a range of subjects have often made headlines.

Exit from the Congress is not a new phenomenon. Congress strength in Parliament plummeted and it lost power in all states of the North in 1967—when it was said that you could traverse on the GT Road from Amritsar to Calcutta without encountering a Congress state government—because prior to that election, unable to accept Indira Gandhi’s leadership many stalwarts left, formed parties, which tied up with non-Congress parties post poll and kept Congress out of power. The 1977 loss was preceded by Union Minister Jagjivan Ram, former CMs H.N. Bahuguna and Nandini Satpathy, and a host of leaders quitting to form Congress For Democracy (CFD) on 2 February, less than a fortnight after Indira Gandhi announcing elections—this development showed that while Emergency was still in force, she could be defied. And if she could be defied, she also could be defeated—the March 1977 deluge followed. Many bids were made to oust Indira Gandhi from the party’s leadership—Congress split twice, in 1969 and 1978, on both occasions Indira Gandhi emerged victorious over the organisational wing. Those who defied her returned with their heads bowed. The election symbol judgement, adjudicated by CEC S.L. Shakhder, chronicled the retreat and surrender of rebel after rebel. Congress(S), which was the counter to Congress(I), was merged into the main party by Sharad Pawar and Ambika Soni in December 1986—Pawar defied Sonia Gandhi over her “foreign origin” in 1999 and formed NCP, soon to ally with Congress; even today NCP and Congress are allies. Retreat of inner party democracy in GOP is a five-decade old phenomenon—even CFD was floated on a “democracy” platform. Azad has merely reiterated what Jagjivan Ram asserted in 1977. Over the years regional parties emerged after Congress leaders quit. Today, while nationally Congress has yielded place to the BJP (and AAP is seeking to usurp the residual space GOP has) in many states, regional parties have kept both the BJP and the Congress at bay. As Azad’s letter points out, Congress seems oblivious to the stark threat to its very existence. Ostrich seems to be the favoured bird. The difference between Indira Gandhi days and now is that both Sonia Gandhi and Rahul Gandhi are “reluctant” politicians—their initial inhibition has fettered their approach. Azad, who now feels sidelined, held many responsibilities both in the party and in the government. He was a good minister and an able organiser—however it cannot be overlooked that the decline of Congress in UP, which began with rebel V.P. Singh winning the Allahabad bypoll in June 1988, happened while Azad was the state in-charge—Congress went on a tailspin and nosedive since.

Two developments are ahead in the Congress almanac. On 28 August, the much-delayed election to the post of Congress President will be confabulated virtually by CWC. After Rahul resigned “in a huff” in May 1919, Sonia has been the interim president (a post on which the party’s Constitution is silent). Prior to her departure abroad for medical

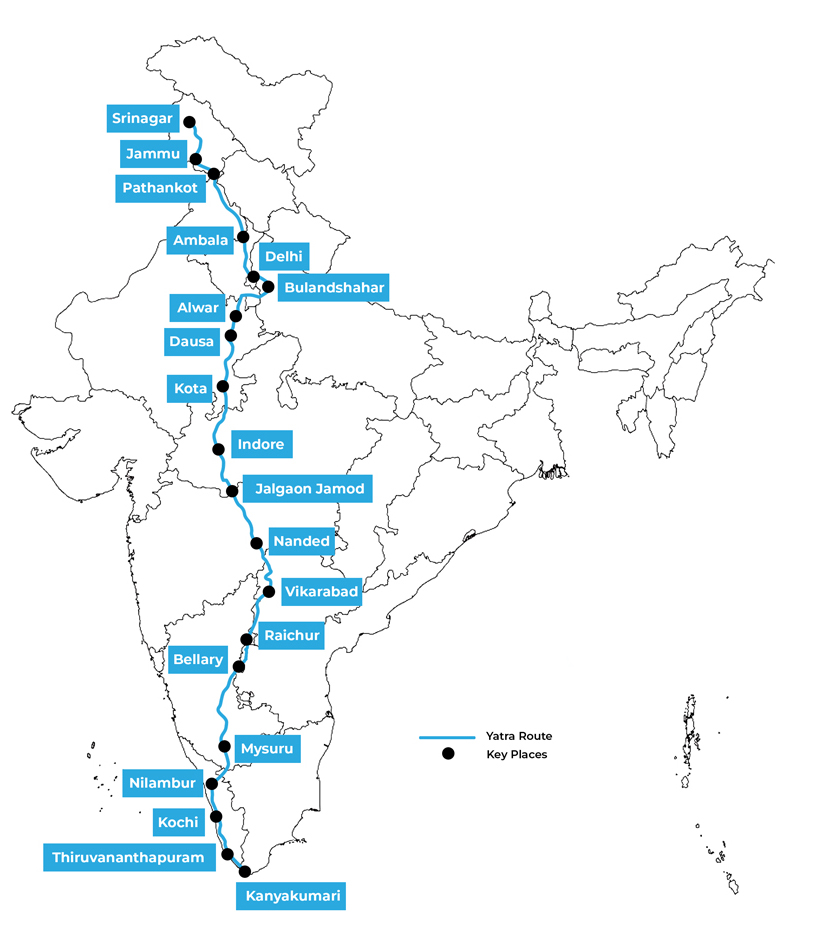

The 3,570 km Kashmir to Kanyakumari Bharat Jodo Yatra, on which Rahul Gandhi will embark from 7 September, is being essentially planned outside the AICC office by NGOs, with whom Rahul Gandhi confabulated last week. Yogendra Yadav, a founder of AAP who was sidelined by Arvind Kejriwal and now runs a party called Swaraj India, is one of the movers and shakers of the campaign. The route of the yatra avoids Gujarat and Himachal Pradesh where elections are due this year. It touches Uttar Pradesh only at its western fringe. Bihar, West Bengal, northeastern states, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh—all are bypassed. The yatra will not even traverse through Chhattisgarh which has a Congress government. Or Jharkhand where the party is a partner in the government. NGOs and civil society activists are public spirited people, however their ability to attract the masses is limited. Their functionaries cannot win elections. Even their funding is mostly sourced abroad, as their ability to collect donations at home is limited. Rahul Gandhi’s pedestrian yatra, which is a laudable effort, thus may not yield political dividend. At a time when BJP is preparing to appoint booth-level operatives for 2024, Congress does not even have polling booths for its internal party elections, which are delayed over the past 24 years. This writer does not believe that a requiem of the GOP is in order—however gloom and doom are writ large.