Will For Children

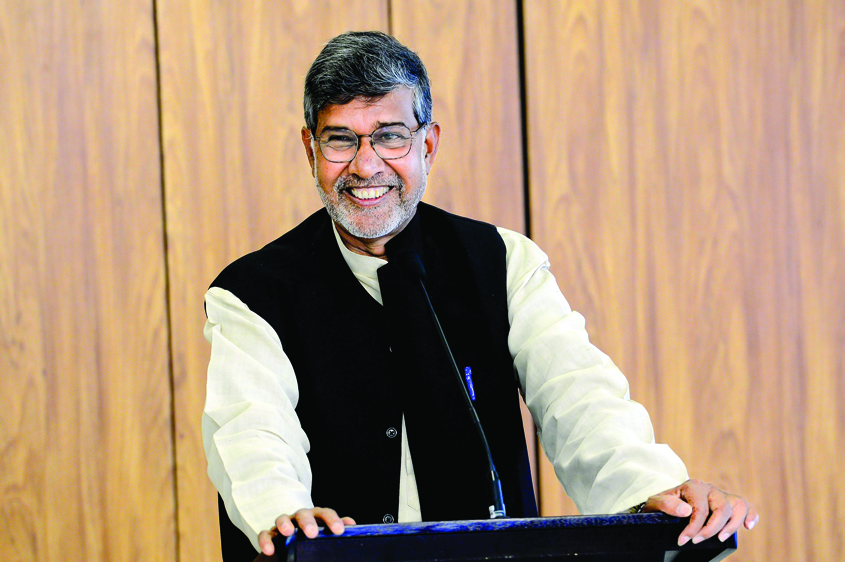

By Kailash Satyarthi

Prabhat Prakashan

Pages: 288

Price: Rs 500

How does one begin to tell the story of Kailash Satyarthi, who at 15 did away with his Sharma surname, to adopt Satyarthi, meaning “Seeker of Truth’’? The lad, along with his friends, in his boyish enthusiasm, had arranged a dinner party for “high caste politicians.” The guests did not show up, spurning the event, once the word spread that the meal had been prepared by “low caste cooks”. That was the revelatory moment, the moment when he dropped his Brahmin appendage in search of answers—answers that continue to stretch out beyond any horizons you can see. Prior to this, what could perhaps, be termed as his Buddhist quest for truth was when in the 6th standard, boy Kailash collected used school books, distributing them with soulful earnestness to school children who would otherwise be attending school sans books, at the peril of being at the receiving end of their schoolmaster’s wrath, armed with a thrashing cane in hand. Since then, Satyarthi has come a long way, freeing 83,000 something children from the shackles of slavery and much more.

Will For Children, the pledging cum promising title of Satyarthi’s book insightfully delves on numberless, perhaps hitherto, untold gut-churning, vividly nauseating stories of children who have been trafficked, enslaved, abused and molested to the point of being left mangled mentally, psychically, spiritually—the carbuncles manifesting in maimed bodies. The author speaks, at length, with passionate intensity on the tragic plight of children, not only in India, but in so many other countries. Of course, the focus is on our little Rams and Rahims; raking in alarming statistics to support the accelerating rate of maltreatment solely because of being born into an economically depressed family with obviously high-levels of illiteracy. And thus, these children are shoe-boxed in asphyxiating factories to make toys and clothes for children who are born in privileged households. Here the phrase that comes to mind: “Prisoner of Birth”. (This also happens to be the title of one of Jeffrey Archer’s books). At the onset of his thesis, Satyarthi vocalises the fact that since women are not treated at par with men and are not, by and large, accorded the respect due to a human being, children, thereby, stand on a perilous precipice. Simply put: A society that thrusts women in reductive roles can by no means flourish. The writer extends the argument by citing how on one hand, we observe Navratri with reverential solemnity and yet on the other hand, Baby Durgas, Lakshmis, Saraswatis are done away in the womb or are sold off to be put on the stomach-turning flesh trade carousel; and how does one live with the blazing on-going vomitous reality of one year old baby girls being “raped.” The author intently computes the figures: “Statistics show that 53% of children in our country are victims of sexual exploitation in one form or the other.”

An abrupt gear-shift: the book also brings to light that every seventh person in the world is illiterate. Sixty million have never set foot in a school and approximately 120 million abandoned their education after clocking in a couple of years.

Here it is emotionally mandatory to pause and ponder over our industrialised insincerity,while zealously articulating our concern for these poor, dear abused children, who, generally speaking, come from the labour class.

Satyarthi illustrates how all religions—be it Hinduism, Islam or Christianity—believe that a child is a reflection of the almighty and so, bespeaks of God Himself.

Some episodes: as a child he learnt Urdu from an ageing cleric, living nearby, who with sparkling effervescence chronicled stories and teachings of Islam. One indelible tale remains radiating within him. God, Allah may assume no form, yet He is experienced in the aura luminescent from the smile of a child cuddling in his mother’s lap. How then, can children, be blasphemously tormented? Listen on: hot molten glass scalded the hands, searing the flesh down to the bone, of a young boy labouring in a factory. His master, infuriated with the mishap, and the financial loss that would be incurred barbarously beat him up. The child worked his bones bare for a reputed Muslim community leader. Mohammad was the name of the child. Multitudinous narratives of the same genre—the names, immaterial, could be Krishan, Pawan, Chris, Peter, Khalid, Pervez…

An abrupt gear-shift: the book also brings to light that every seventh person in the world is illiterate. Sixty million have never set foot in a school and approximately 120 million abandoned their education after clocking in a couple of years. Ironically indeed, those who continue to attend school can barely read, write or do simple edition or subtraction. Teachers, where are you? On paid sabbatical? Or employed as gurus on dubious grounds, entering portals of learning from a tumbled down, dilapidated backdoor.

On receiving the Nobel Prize for Peace along with Malala Yousafzai in 2014, Satyarthi found that some papers of his “acceptance speech” had gone missing. A story that forever remained with him in his long battle for children came to mind. Fortified by it, he marched on, invoking the audience to join his movement. Hear this: “Once a fire broke out in the forest. All the birds and beasts, including the lion, the king of the jungle, started running for their lives. In the midst of the chaos, the lion caught sight of a hummingbird flying towards the fire. Shocked, the lion asked, ‘What are you trying to do?’ The hummingbird, indicating its beak, said, ‘I am carrying a drop of water to extinguish the fire.’ The lion was amused. It said, ‘How can you douse a fire with just a drop’? But the hummingbird was unshaken. I am doing my bit, it said.”

It goes without saying that the hummingbird’s tender whole-hearted steadfastness is peerless. However, the terrestrial take: every droplet sways the waves of the ocean.

Dr Renée Ranchan writes on socio-psychological issues, quasi-political matters and concerns that touch us all