Overhaul of education, revamp of export strategy and getting 50% farmers out of farming should be part of revival roadmap.

It is the last Sunday of 2019 and as we prepare to usher in a new year and a new decade, I have a wish list for what all we should hope to achieve. The Indian economy is ending 2019 on a sombre note. The IMF’s Chief economist Gita Gopinath has already announced our growth rates will be revised downwards, but that doesn’t mean 2020 will not look up. While the jury is out on how soon growth will revive, time is opportune for the government to focus on a long term vision for the next decade. After all, our long term plan is to be a $10 trillion economy by 2029. It will hinge on a variety of reforms and a holistic outlook towards growth, which should be laid out as we usher in a new decade.

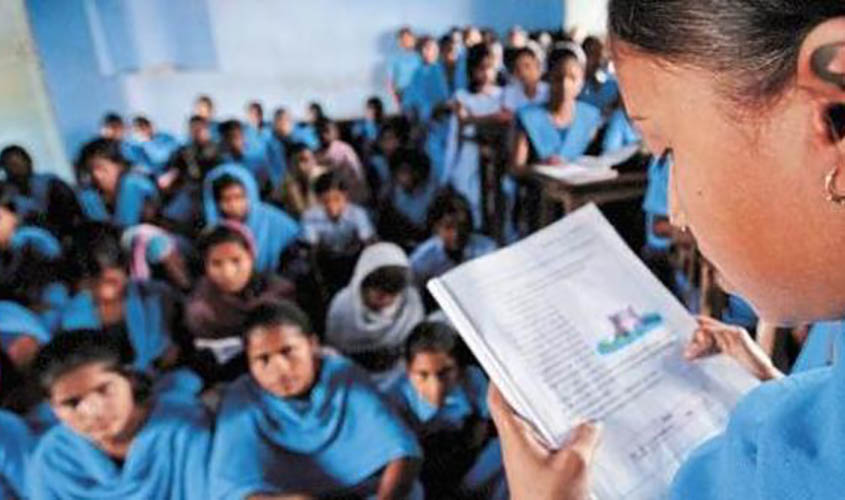

Firstly, there has to be a revamp of the education sector. We need to ask ourselves why is it that most graduates are unemployable by industry and struggle to get a clerical post. India needs to have a proper policy towards private/semi private universities without dilution in quality. More and more universities are mushrooming, but are producing sub-standard talent (at exorbitant course fees). Add to this is our fascination with teaching basic skills to school dropouts without knowing how soon these skills will become obsolete given the fast pace of technological change. For the push India is making towards green cars, what happens to all the ITI degree holders in automotive engineering/skills? Needless to say they will have to upgrade, learning their lesson the hard way. Yes, we manage to get more kids in school because of the free meal they get, but their learning outcomes need to have some clear guidelines. Unless we do that, we will perpetually have a problem of a complete mismatch between employable skills and those that are students and graduates have.

Secondly, we need to start focusing on our export sector. It contributes 11.13% to our GDP and has been stagnant for many years. It was in FY2015 that exports contributed 14.75% to GDP (highest ever) and then slipped to a 15-year low of $262bn in FY2017 post DeMo. The history of economic growth tells us that for any country to make the shift from developing to developed, exports (especially from textiles and ready-made garments sectors) are crucial. More so, since these are labour-intensive sectors employing more women than men. As is well known, labour force participation rate of women has fallen sharply in the last few years. Between April and August this year, textile exports fell by 9.7% to $7 billion—this was the steepest fall in five years. Exports of ready-made garments between April and September this year increased by a tepid 2.2% to $7.8 billion.

Yes, we didn’t sign the RCEP since it would have meant a glut of products from China and other countries in our markets, but it also warrants introspection as to why Indian industry is so uncompetitive. While the government has already announced tax incentives that kick in from 1 January, land and labour are the big impediments India needs to address to unlock potential of Indian exports. $5 trillion is a goal that needs to have Indian exports accounting for at least 5% of global trade. At present, they continue to be around 1.6-1.7% mark. It was in 1948 that Indian exports contributed 2.2% in dollar terms to world trade. China’s share of global exports was 12.8% in 2018.

With cost of credit for Indian exporters being much higher than their Chinese and Vietnamese counterparts who have almost zero burden, the government needs to extend interest equalisation benefits of MSMEs to all exporters. Too many duties and levies make Indian exports uncompetitive and there is an urgent need to rationalise those and bring them under GST (electricity and petroleum).

There is a mismatch between high-value export items in the world and that of India. From primary and low technology goods, India needs to shift focus to medium and high-tech goods by adopting new technologies. This needs focus on skilling and promotion of innovation which unfortunately is not encouraged in our archaic education system (which has already been raised).

Finally, it is agriculture that needs maximum attention. Water-guzzling crops growing in areas where ground water table is being depleted lead to excessive use of power (given free due to political concerns) and leads to too many distortions. For starters, industrial power is charged at a much higher premium due to freebies to agriculture making Indian industry uncompetitive. The rich Indian farmer is not an oxymoron and they need to start paying taxes. It is a political hot potato but possible with deft political manoeuvring. Almost half of our population is engaged in agriculture, contributing just 16% to our GDP. While US is the extreme case of productivity where 2% of its population creates food for 2 billion people, for most East Asian economies (more comparable to India), only 10% of the population is employed in agriculture. India needs lesser farmers and higher farm incomes. Enough has been written about policy that will make farming viable, so without going into details, reforms need to focus on all fronts—input costs, fertilizer costs, tweaking MNREGA to coordinate with cropping cycles, focus on creating effective supply chains. Finally, farmers don’t need just freebies, they need viable alternatives. It’s only when we create an ecosystem to take farmers out of farming into industry, that our $5 trillion (or $10 trillion by 2029) will be achieved. In the 20-year period between 1992 and 2002, China ensured half the people who left farming were brought into industrialisation. India needs a similar vision and an action plan. That is my wish for 2020, a long term vision for the next decade that will make us not just a middle income country, but closer to even a high income country. The next decade will belong to us, provided we have a roadmap.

Gaurie Dwivedi is a senior journalist covering economy, policy and politics.