A new book on the Indian modernist Ganesh Pyne, who died in 2013, throws into sharp relief previously unknown aspects of his life and work. The critic Pranabranjan Ray, the book’s author, speaks to Bhumika Popli about his decades-long engagement with Pyne’s art.

“Ganesh Pyne is an enigma to me,” says senior art critic Pranabranjan Ray.

Ray was closely associated with Pyne (1937-2013) and has seen the artist transition, from being an amateur, into a serious painter. He has also written a book on the artist, entitled Ganesh Pyne: A Painter of Eloquent Silence, which includes 96 illustrations by Pyne, along with Ray’s essay exploring various facets of Pyne’s oeuvre.

“Even though I knew him for almost 50 years, I would still say that the artist remained an enigma to me,” Ray tells Guardian 20 in a telephonic interview. “He was very social, interested in knowing about the lives of people around him and also had a wide curiosity about the world. But there was another side to his personality as well, the one which was quite impenetrable by others. It was like he would keep something to himself and that would only come out in his work,” he says.

Pyne’s body of work is a good fit in the modernist context. The artist lived through both colonial and post-colonial times in India and witnessed death and destruction at a very young age. During the Great Calcutta Killings of 1946, when Pyne was nine years old, he looked too closely at violence and bloodshed. At that time, his family was also temporarily displaced from their ancestral home.

In this centuries-old home, under the dim lights of the lamps in the evening, Pyne used to listen to folktales and Puranik myths.

As an artist, Pyne became known for his morbid themes. His work seemed to spring from his obsession with death. His paintings were as dark as the colours he preferred.

But Ray has another way of looking at Pyne’s works. According to him, the artist constantly strove to fight the darkness. Ray says, “The fire, the light, the flame and the lamp in Ganesh Pyne’s work retain their commonly held associations with negation of darkness.”

Pyne’s light and dark play on the canvas reminds us of the chiaroscuro style which emerged in the Renaissance period. But Ray warns us against categorising the artist’s works into that bracket. “Pyne’s use of light and shadow is very much against the principle of chiaroscuro and we can refer his works in relation to Abanindranath Tagore, Rembrandt and Paul Klee. They remain very important sources of his visual language,” says Ray.

Once in the Bengali literary magazine Desh, Pyne himself expressed similar thoughts: “Once in my paintings I aimed at fusing Abanindranath mode of viewing and Rembrandt’s use of expressive light and darkness.”

Ray has also compared Pyne’s artworks with a French-Russian painter of Jewish origin, Marc Chagall, also an acclaimed modernist. Ray writes, “The only other modern artist with whose method of visual narration Pyne has some family resemblance is Marc Chagall. But then Chagall’s work demands an acquaintance with Hebrew and Yiddish mythology, whereas Pyne does not demand any such background knowledge, even where he refers to particular ritual objects and archaic symbols.”

The subtitle of Ray’s book—A Painter of Eloquent Silence—is taken from poet and filmmaker Buddhadeb Dasgupta’s film on Pyne. It is in this film that the artist has been called a “painter of eloquent silence”. In Pyne’s paintings, the vast empty areas, cloudless day-skies, the calm seas and so on, all point towards a creative imagination of a lonely traveller who faces some lingering threat. “His journey has a hanging threat of death,” says Ray.

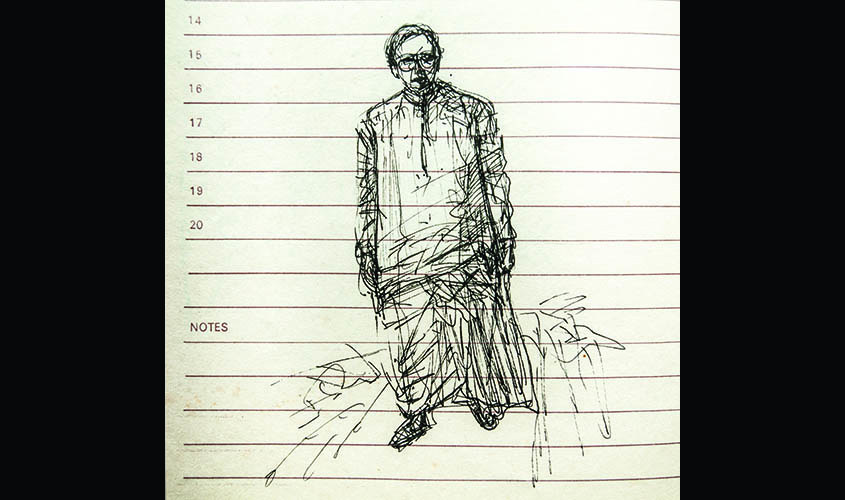

While reading Ray’s book, we also become familiar with Pyne’s work as a book illustrator. Pyne worked as a sketch artist at Munder Mullick’s studio in Calcutta for animation films back in the pre-digital era.

In Ray’s opinion, Pyne’s works between dating from 1960 to 1995 are very remarkable. He draws our attention to a few tempera paintings from the 1970s, such as The Harbour (1975), The Night of the Merchant (1985), The Fisherman (1972) and so on. According to Ray, the events presented in the works are too imaginary to be comparable to real life, but the placements of motifs and the use of colours suggest “parallels to the events and situations from the beholder’s own memory and knowledge bank”.

Ray doesn’t consider Pyne’s output post-1995 really significant, “because the artist was playing with certain permutations and combinations of his previously done work and there was no new revelation in later stages of his career”.

Ray compares Pyne to painters like Somnath Hore and Bikash Bhattacharjee. He says, “All of them somehow rejected borrowed Eurocentric modernism. They were interested in the happenings of the time they belonged to. But each one had a separate kind of perspective to reality. There was hardly any formal give and take between them but all of them were motivated by their experiences of the here and now.”

‘Ganesh Pyne: A Painter of Eloquent Silence’ is published by Delhi’s Lalit Kala Akademi and Akar Parkar, Kolkata