Centuries ago, children born in Sparta in Ancient Greece were considered the state’s property. A similar model of anti-family childcare is being adopted by several Western countries today.

According to the legend of Sparta, a woman from Attica once asked the Spartan queen Gorgo, “Why is it that only Spartan women can rule men?” Gorgo replied, “Because we are the only women who give birth to men.”

Sparta and its “ideal” children have inspired generations of Western educationists, leaders, politicians and thinkers. The influence on child-rearing practices, especially in children’s education, has been profound. Hence, we need to explore what these “men” were really all about, how children were raised to be “men” from infants and toddlers, and the kinds of initiation and rites of passage they had to endure. As evident from the anecdote, children were consciously reared to be glorious “men” implying there was a clear philosophy of child-rearing.

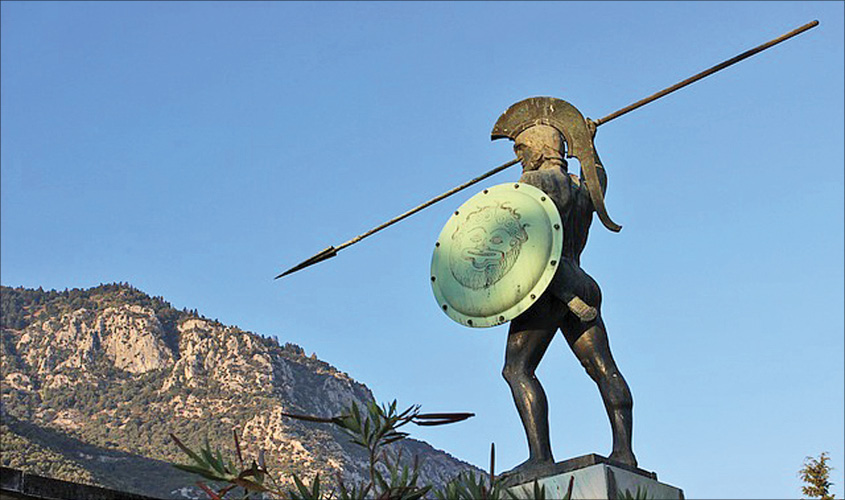

Sparta was a militaristic society where the entire ethos and values were driven by war and conflict. So the warrior classes had an exalted position. The glory of Sparta derived from conquests and victory on the battlefield. Sparta as a polity drew its sustenance from the warrior ethos. Warfare was central to its existence, its very raison d’être, and there was a sense of a permanent state of siege among its ruling classes. In this background, every child was seen as a potential soldier—future warriors for the sacred task of fighting

for Sparta.

Spartan women or mothers had only one goal: to produce strong and valorous soldiers.The values and ethos of motherhood and child-rearing practices were designed to “create mothers who would produce the best hoplites and mothers of hoplites”, where “hoplites” means an armed soldier. Spartan women were expected to fulfil this responsibility successfully and it is recorded that the typical farewell words of a Spartan mother to her son embarking on a voyage for the battlefield would be, “come back either with your shield, or on it” (Plutarch). In other words, the mother refuses to welcome home a defeated son, but only one who is victorious, or dead in the battlefield. There is a paradox about the social position of the Spartan women; although living in a highly masculine militaristic society, they enjoyed a higher social status than their Athenian counterparts precisely because they were engaged in raising good soldiers and a woman was treated as the mother of a potential brave warrior.

Sparta operated a system of eugenic selection right from the time of birth; the State decided whether infants were to be permitted to live. Spartan parents presented their infants for evaluation before a Council of Elders who were officials of the State. They judged whether the child was fit to live or was to be terminated based on his physical build, sturdiness and strength. If the infant was approved by the State Council the “the women used to bathe their newborn babes not with water, but with wine, thus making a sort of test of their constitutions. For it is said that epileptic and sickly infants are thrown into convulsions by the strong wine and lose their senses, while the healthy ones are rather tempered by it, like steel, and given a firm habit of body”(Plutarch, Lycurgus, 16. 2-4).

Children were seen as the responsibility of the State; a physical representation of the “polis” and its shared culture and civilisation. Children were considered to belong entirely to the State and country and not to the families, nor were they considered independent individuals.

Plutarch (Lycurgus, 24.1) records: “The training of the Spartans lasted into the years of full maturity. No man was allowed to live as he pleased, but in their city, as in a military encampment, they always had a prescribed regimen and employment in public service, considering that they belonged entirely to their country and not to themselves…”

Polis identity, which was central to the rearing of children and maintaining families, was defined as “the accumulated cultural traditions and ideologies regarded by a Greek city-state as the framework for proper citizenship” (Warrick, 2013). The legitimacy conferred by the State or City-State on the idea of proper citizenship and shared cultural ethos, traditions and civilisational values conferred a certain prestige and status, making it mandatory for families and their children to follow and adhere to them closely. In other words, the State or City-State was the final arbiter in defining what was proper citizenship. Cultural ethos and civilisational values did not emerge spontaneously or organically from the folk culture. As a Spartan you could not deviate from the standards set by the State.

Children’s education and rearing was one of the effective and widely used methods of the State for reinforcing the polis identity. The Spartan State exercised close supervision and control over the formative years of boyhood so that boys could fulfil their purpose of growing into good and able warriors. In this way we see an intrusive, interventionist State with very visible “long arms” akin to the modern social welfare State in the domain of family welfare and child education.

Spartan children were raised to be good and brave soldiers imbued with the warrior ethos, in tune with the philosophy of the State of respect for physical strength and military prowess. Till about the age of six, Spartan children were placed under the supervision of nurses who prepared them for the challenging Agoge system by teaching them at an early stage of infancy to be brave, daring and free of emotions, like the fear of darkness (Garland, 1998). In Spartan society, men were expected to serve in the army until the age of 60, hence there lay ahead a long stint of warrior-hood for these children.

Once the male children turned seven, they were inducted into the Agoge system, thus terminating their childhood in a conventional sense. Agoge were public educational institutions within the fold of the State, where the children were raised in a strict and strenuous manner. Most remained there into adulthood till the age of 30.

Obedience and courage was what the instructors sought in the young boys. Plutarch (Lycurgus, 16. 5- 7) describes it thus: “The boy who excelled in judgment and was most courageous in fighting was made captain of his company; on him the rest all kept their eyes, obeying his orders, and submitting to his punishments, so that their boyish training was a practice of obedience.”

The boys were organised into small groups according to their age. They were kept under the supervision of elderly men or masters who would closely monitor their conduct in the playing fields while doing sports and make them play games of battle and combat. The boys’ responsiveness in terms of boldness and aggression towards opponents was observed and recorded to identify future soldiers and generals.

Intellectual competencies of reading and writing were imparted adequately enough to acquire mastery over the basics. However, the focus was on training the boys to “obey commands well, endure hardships and conquer in battle” (Lycurgus, 16. 5- 7).

As the boys grew older they were subjected to a harsher physical regimen of exercise and sports, being made to walk barefoot and dress minimally. From the age of twelve years they were given only one cloak to wear. They were required to possess a rugged, robust physique with hard, dry flesh and strict limits on baths and ointments.

This basic lifestyle and hard training was continued till the boys turned 30 years of age when they started living in dormitories and being prepared to be called for active military service. They were allowed, or even encouraged, to marry and beget children, which again was driven by the need to maintain the adequate number of citizens and manpower for the army.

At the end of the Agoge tenure and boyhood training, the children were meant to metamorphose into ideal citizens of Sparta: good soldiers, ever prepared for battle, belonging to the State and not their respective families. This notion of the separation of children from parents and family, and being adopted or even “confiscated” by the State is repeated in the thinking of today’s child welfare services. Although the modern Western welfare states are not engaged in perpetual warfare, the Spartan approach to child rearing is reflected in the work, indeed the self-justification, of child welfare services regarding the moulding and shaping of young minds and character. This time around it gets worse since there is no grander purpose with no great philosophical minds guiding the process, but petty, opportunistic, careerist social workers.

The ancient Spartan model of educating and raising children through the notion of a “polis identity” left an indelible mark on the Western world in terms of the philosophy of education. The Western obsession with Sparta and its ideals have been termed as “Laconophilia”. This ideal of inculcating within children a shared cultural and civilisational ethos appears as a constant theme in the subsequent educational systems constructed through the Western world, especially in Europe. The oft-repeated quote that:“Tom Brown’s School Days owes more to ancient Sparta than it does to Christianity” (Harker, 1996) reflects the continuing influence of Spartan thinking in England in later children’s education. 19th and 20th-century English public schools have similarities with the Spartan model in terms of philosophy of education, imparting scholarship, character building and personality development being part of the curriculum with almost no involvement of the family. In other words, in this view, the family and the parents had little or no role to play in the education of the children.

Prussian cadet schools or academies which arose during the mid-19th century also echoed the values of the Spartan education ideal. These cadet-academies trained boys from the age of 10 for a military career in the Prussian Officer-Corps, the most prestigious and elitist stratum of the society, effectively a training for the ruling classes of Prussia. The French lycée were also influenced by the Spartan educational ideal. The French thinker Louis Michel Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau (1760-1793), counselled for a Spartan-style education system for all French citizens, both male and female, in the state-organised schools to instil a strong Republican spirit in order to churn out citizens who could defend the Republic. This influence of Spartan ideals and the organisational influence of the Agoges in later Western education systems deserves a separate article for this continuing series. The legacy of Sparta’s children continues to linger in varied forms to this day.

Kaustav Bhattacharyya is a PhD from Cass Business School, London. He is an entrepreneur and commentator on Indo-European affairs

The Global Child Rights and Wrongs series is published in collaboration with www.saveyourchildren.in, lawyer Suranya Aiyar’s website critiquing the role of governments and NGOs in child-related policy