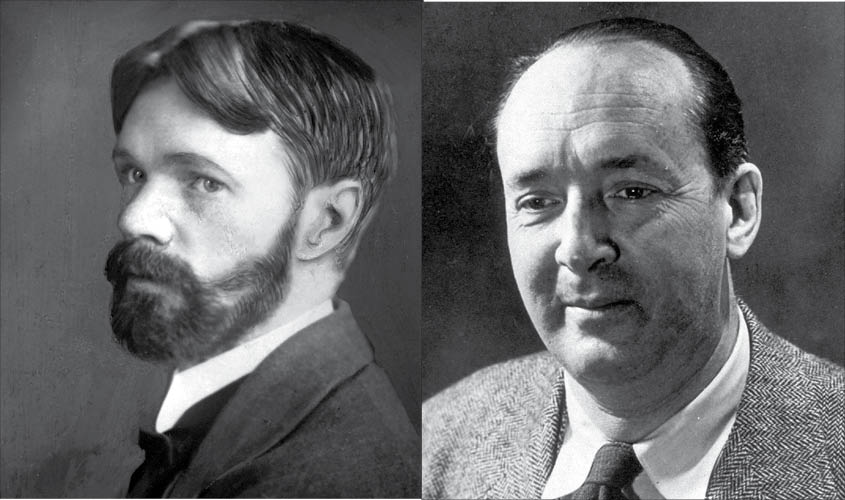

Vladimir Nabokov and D.H. Lawrence each wrote a major novel (Lolita, Lady Chatterley’s Lover) that was banned and unbanned and banned again before being cut free.

There are other similarities. Each was a great traveller, as if in perpetual self-exile, and drawn to America. Each disliked heavy, didactic fiction. Each was a sensualist on the page, his rods and cones consistently assaulted by the world’s beauty. Each recoiled from Freud. Each had a well-tended ego.

Each has stern and persuasive feminist critics. In Jeanette Winterson’s memoir Why Be Happy When You Can Be Normal? (2012) she traced her nascent political awakening to reading Nabokov when young and thinking, “He hates women.” Kate Millet, in Sexual Politics (1970), lowered the boom on the “liturgical pomp” of Lawrence’s sex writing. His reputation was punctured and will never fully reinflate.

The similarities stop there. Read side by side, they seem to conduct a mutual criticism. Nabokov’s prose style was cool; it induced little shivers; he delivered cut and polished gemstones. Lawrence’s sentences were colicky; they burned hot and frequently overheated. Impurities clung to his diamonds. Nabokov had highbrow standards. Lawrence, God bless him, simply had high ones.

They probably would not have enjoyed each other’s company. Nabokov came from aristocracy and liked to live in well-appointed hotels. Lawrence, whose father was a coal miner, was fundamentally a bohemian; when he got too comfortable, he felt like smashing something.

They were nearly contemporaries—Nabokov was born in 1899, Lawrence in 1885—but Lawrence died at 45 from tuberculosis, and they seem to belong to vastly different eras. It is curious to consider that Lawrence, had he not been unlucky, might have lived to see Chuck Berry and the Kennedy assassination and maybe even to write about them.

Two new books offer looks at these writers’ nonfiction prose—essays, travel writing, book reviews, etc. The Nabokov book, Think, Write, Speak: Uncollected Essays, Reviews, Interviews, and Letters to the Editor, is mostly for completists.

Nabokov disliked the Q and A. “I think like a genius, I write like a distinguished author, and I speak like a child,” he wrote. Yet two-thirds of Think, Write, Speak is made up of interviews, more than 80 of them, most conducted after the publication of Lolita. One suspects that Nabokov, spying this talky book from the Great Beyond, must feel as if someone had dug up his bones, hanged him and buried him again.

Nabokov is Nabokov. He dispenses gleaming shards. (“My dream would be to have a pencil that always stayed sharp.”) He speaks of his fondness for butterflies, boxing, soccer and afternoon naps. He defends Lolita against its moral detractors. (“Humbert Humbert is a villain.”) But the same topics keep coming around, as if on a sushi belt.

Here is the best passage in Think, Write, Speak, one that, were I a tattoo person, I would consider advertising on my forearm:

“In a sense we are all crashing to death from the top story of our birth to the flat stones of the churchyard and wondering with an immortal Alice in Wonderland at the patterns of the passing wall. This capacity to wonder at trifles no matter the imminent peril, these asides of the spirit, these footnotes in the volume of life are the highest forms of consciousness, and it is in this childishly speculative state of mind, so distant from commonsense and its logic, that we know the world to be good.”

It only makes sense that the Lawrence collection, The Bad Side of Books: Selected Essays, is the stronger volume. (At $19.95 it’s also the better bargain.) Its editor, Geoff Dyer, has chosen his favourite of Lawrence’s nonfiction, not merely relying on previously unpublished work.

Most of this material was new to me, and I enjoyed this book enormously. His 1925 essay, “Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine” (the animal perished after Lawrence, who disliked

His 1921-22 essay, “Memoir of Maurice Magnus”, is perhaps the best portrait of a sponge I have read. Lawrence’s rather grand friend kept asking for money until Lawrence could take it no longer. One ends up admiring this writer’s ability to be cruel, to be a ramrod in print. About his ungrateful friend, who ultimately commits suicide, Lawrence writes: “I could, by giving half my money, have saved his life. I had chosen not to save his life. Now, after a year has gone by, I keep to my choice. I still would not save his life.”

In his 1924 essay “A Letter From Germany”, Lawrence is uncannily prescient about Europe’s shifting temperament. He does not mention Hitler. Yet he writes: “Something has happened. Something has happened which has not yet eventuated. The old spell of the old world has broken, and the old, bristling, savage spirit has set in.”

In “Art and Morality”, an essay from 1925, Lawrence essentially predicts the selfie. Speaking of the new Kodak cameras, he writes: “To every man, to every woman, the universe is just a setting to the absolute little picture of himself, herself.”

His writing about the shattering nature of syphilis is both devastating and a bit sly. “You could joke with the word ‘pox,’” he wrote. “You can’t joke with the word ‘syphilis.’” Reading Lawrence’s writing about sex, in general, leaves you suspecting that he walked around with perpetual rugburn.

The Bad Side of Books ends with Rebecca West’s remembrance of Lawrence, published shortly after his death in 1930. Lawrence would have admired her refusal to lapse into panegyric.

West tweaks Lawrence and turns him into a Monty Python sketch by recalling how he was known to arrive in a new city, race to his hotel “and immediately sit down and hammer out articles about the place, vehemently and exhaustively describing the temperament of the people.”

The really funny thing is, he had that enzyme that allowed him to convert what was in the air to what flew out of his fingers. Lawrence’s deadline excursions nearly always hit their mark.

© 2019 THE NEW YORK TIMES