Included in a recent anthology of memoirs by the greats of Indian cinema, this portrait of the poet Sahir Ludhianvi, now out in an English version, was written in 1948 by Kaifi Azmi for an Urdu magazine.

Among the various threats looming over the film industry these days, Sahir Ludhianvi appears to be the most severe of all. One doesn’t know when he may decide to turn into a producer and a director along the course of writing songs. This leaning of his is an influence of the city of Bombay. He was a poet when I first met him and will probably remain one when I meet him for the last time—not because his abilities are limited to poetry but because production, direction or any similar department doesn’t have the strength to confine Sahir.

Like the regular “scheming” middle-class youth, Sahir too cannot halt at one point. To keep moving on is his aim in life and, like Cavalcanti, he doesn’t believe in treading the conventional path. The bitter realities of life have been following him since his days as a student.

He doesn’t want to run, yet he is running. The field that lies ahead of him is huge, and the destination at the end of it is bright. But how does one cross that stretch of “two furlongs” on the road at which thousands of young people known to Sahir are carrying the weight of their own beings? Strolling, meandering, sprinting. As their pace shrinks by the day, they are getting trapped in their own illusions.

Sahir was associated with student organisations during his college days; he moved out with his heart full of empathy for them. Thereafter, he got besieged by the constraints of life—the kinds that can defeat as well as get defeated by anyone. At some point of time, everybody ponders over how one should lead one’s life. However, the questions that our young scholars and poets face are a little more complex than this. They have to concurrently deal with two questions —how to earn a living and how to nurture one’s inclinations. Unemployment can make life difficult, but at the same time, one’s interests can also never thrive in mundane jobs.

Sahir compiled a collection of his poems and set out to sell it; at that juncture, perhaps he wanted to make a living out of being a writer. But when faced with a situation where agents are paid a commission of 25 to 33%, while a writer receives a royalty between 12 to 15 %, one has to pause and think about whether to write a book or sell one.

There was another problem that Sahir must have faced—who would publish his book and who would buy it? So what if he was a talented poet, he was still nowhere close to fame—the yardstick that usually impresses people. The demand for his words in the market was not enough for the servers of language and literature to rake in the desired profits. It was extremely courageous of Preetlari to agree to

publish the book.

In 1943, other than

M. Hasan Lateefi, I wasn’t aware of any other poet from Ludhiana. When a copy of Talkhiyaan came for review in Qaumi Jung (Naya Zamaana, Bombay), I read it and was filled with feelings that were a mix of joy as well as surprise. I was glad that the poetry of Sahir was devoid of the entangled, indeterminate and soulless indulgences that young writers passed off as poetry during the time of the War; I wondered where this talented poet had been hiding all this while.

I first met him at the Hyderabad railway station. A conference of Progressive Writers Association was scheduled in the city and I was part of a large entourage that had arrived there from Bombay. As we alighted from our train, Kaleemullah informed us that Sahir was in another train that was to reach five minutes later. I stayed back along with the volunteers of the conference to receive him.

The train arrived and Sahir stumbled out of his compartment; five-and-a-half feet tall, which could be stretched to six feet if straightened, long supple legs, thin waist, broad chest, pox marks on face, firm nose, beautiful eyes with a shy thoughtfulness in them, long hair, sticky walk, attired in shirt and trousers and a tin of cigarettes in hand.

As I stepped forward eagerly and introduced myself, Sahir stretched out his arms and gave me a warm hug. I personally prefer an embrace to a handshake but at that moment I got a bit worried thinking that the poor man had possibly fainted. Just as I was about to enquire, he quietly extended his tin of cigarettes towards me. I felt that asking anything at that point would be offending the immense affection displayed by him. Yet, the silence needed to be broken, so I asked, “Why isn’t [Ahmed Nadeem] Qasmi saheb here?” He put his arm on my shoulder and replied in scarcely two words as we walked out of the

station.

The story of Sahir’s life didn’t turn out to be an unheard one. Scion of a feudal landlord from Ludhiana, as he joined college after finishing his early education, the Second World War broke out. By the time he came out of college, the basic commodities needed in life had made their way to the black market, and northern India was staring at an acute famine that claimed 30 lakh lives. It’s not hard to imagine how life turns out in such situations, but there is also another chapter in Sahir’s tale.

His father married 11 times. Sahir was still at a tender age when differences arose between his parents. Custody of the young boy developed into an issue of contention. The patriarch needed an heir, and since unfortunately he didn’t have any other offspring, he escalated his domestic case to a legal one. In front of the magistrate, Sahir expressed his wish to stay with his mother. As a result, his father had no further interest left in him, and the ties of blood and soul steadily deteriorated. So much that when Sahir began his studies, his father felt really insulted—how could the son of such a big landlord attend school! Later, when he came to know that his son had started writing poetry, the anger turned into contempt.

Although when the news reached him that the magistrate of Ludhiana was an admirer of Sahir’s verses and would even send his car to fetch him, paternal love was re-ignited; he started saying to those he knew, “My son has become a poet and he visits the magistrate’s bungalow.” However, the dear son could still not benefit from the father’s wealth, and the expenses for his education were borne by his mother and maternal uncle.

Those who don’t know Sahir closely might be unaware that the disappointment with his surroundings along with the presence of some under-developed skills has cultivated a lot of skepticism in his temperament. If a producer increases his fee, he starts thinking whether there is a motive behind it; if a girl wishes him, he gets worried about a raise in his list of failures, and if a girl actually falls in love, then his heart proclaims:

Teri saañsoñ ki thakan, teri nigaahoñ ka sukoot,

Dar-haqeeqat koi rangeen sharaarat hi na ho

Maiñ jise pyaar ka andaaz samajh baitha hooñ,

Woh tabassum, woh takallum, teri aadat hi na ho

[The weariness in your breath, the silence in your glance,

In truth, could all be a mischievous trick

What I may consider signs of romance,

Those smiles, that eloquence, could merely be your habit]

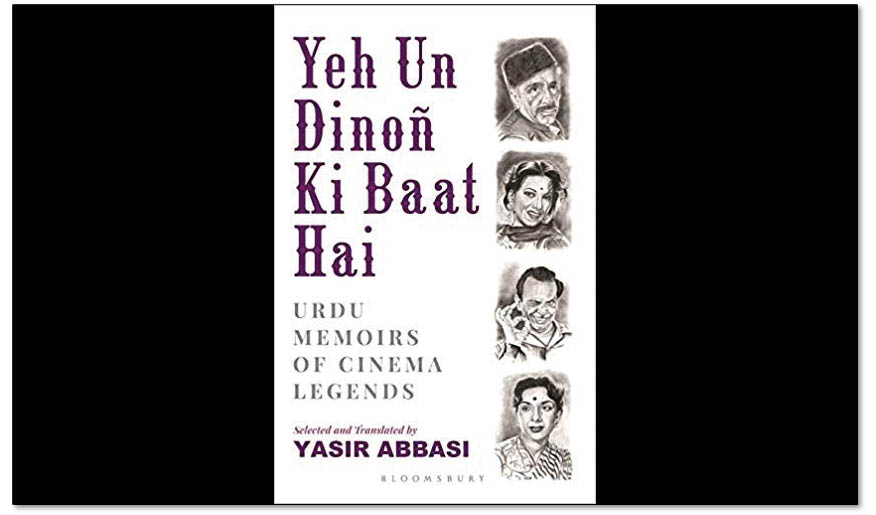

Excerpted with permissions from ‘Yeh Un Dinoñ Ki Baat Hai’, selected and translated by Yassir Abbasi,

published by Bloomsbury India