Born in British India into an enlightened aristocratic family of Bengal, he was part of the Indian Renaissance and brought it to its glorious apogee.

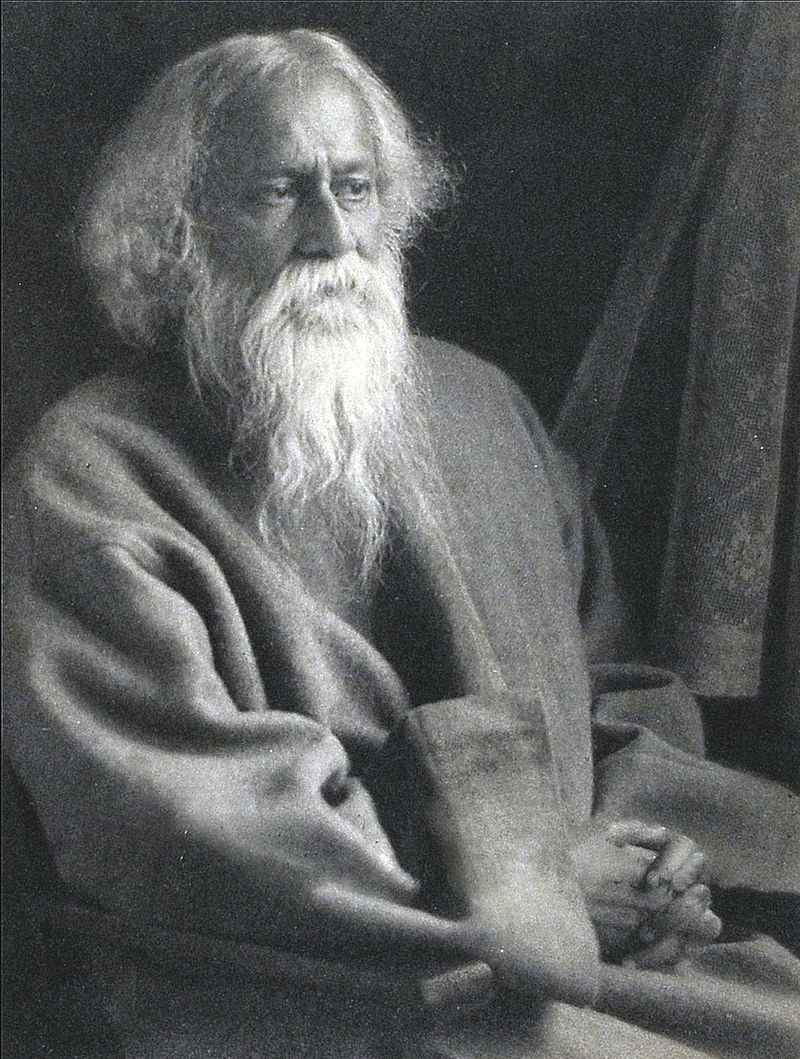

Millions of words have been written about the resplendent figure of Rabindranath Tagore. On his birth centenary in 1961 a massive volume was published by the Sahitya Academy in which distinguished and brilliant men and women from different disciplines and talents from Asia, Europe and Africa paid radiant homage to the greatest son of modern India, and one the extraordinary personalities of the second millennium. In my slender volume on Gurudev on his 150th birth anniversary, I have humbly enumerated many aspects of his genius. But no praise is adequate for him, nor can anyone fully describe his versatility in so many spheres; poet, novelist, composer of thousand songs, seven dance dramas, children’s storyteller, teacher and educationist, initiator of rural development, traveller, philosopher, ecologist and finally—both a fervent patriot and universal man.

Born in British India into an enlightened aristocratic family of Bengal, he was part of the Indian Renaissance and brought it to its glorious apogee. Love for India, her people, her scenery and seasons, her heroes and heroines, her grief and ordeals, glories and achievements, illumined his creativity and his very existence. Through his work and thoughts he carried the civilizational message of India to the West, Russia, East and West Asia and Africa. Citizens of these nations—exalted and humble—revered him. When his words touched their inner chords they paid him homage. The Nobel Prize for literature won him universal fame. From being a great Indian he became vishwakobi—or world poet. His famous work The Religion of Man was read all over the world while dark shadows of war were gathering on the global horizon.He was named Uomo Universalis—the universal man.

For Rabindranath love for one’s country was an expanding process. He inherited a national cultural tradition from Ram Mohan Roy on the one side and the Orientalists and Indologists on the other who made India’s ancient heritage known to the world. Eminent Indians such as Ram Mohan Roy, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Swami Vivekananda and Mohandas Gandhi revitalized this tradition and took it forward. Rabindranath brought these traditions to an aesthetic fruition. The Indian Renaissance reassessed cultural values and traditions of the past. Rabindranath read widely on world history through the writings of Hegel, Keyserling, Spengler and Sorokin. He reflected on the evolution of Indian culture and history, on the conflicts between the early indigenous people and later migrants, between Hindu religious sects, between Moghuls, Marathas and Sikhs.

His treatise—Bharat Tirtha—Pilgrimage of India was published in English as A Vision of Indian History. This work received high praise from India’s celebrated historian, Sir Jadunath Sarkar. Rabindranath Tagore’s reflections on the subject led him to the conclusion that in spite of the clashes and conflicts between various religious and ethnic groups these disparate people strove for a common purpose—peace and prosperity in the country, tolerance of different viewpoints, and an amicable coexistence.

The poet saw the historical destiny of India as different from other countries. Indian civilization, according to Tagore, was not centered on political power or territorial expansion as was the Roman or colonial empires, but on development of culture and society and a vigorous interplay. He felt that social cohesion and social reliance rather than political objectives fortified a nation.

Unlike fervent nationalists who held Britain responsible for subjugating India, Rabindranath saw colonial rule as an outcome of the evils of caste and superstition, of prejudices that create resentment, and a divisive society that paves the way for the betrayals which usher in foreign rule. When resisting the formidable power of the British Empire, Tagore insisted that a people do not become great by aggressive policies

Rabindranath believed that a people grew not by seclusion and isolation from others but by a vigorous exchange of ideas, art-forms, skills, and beliefs. This free exchange was what enriched individuals as well as nations. This central idea is reflected in his famous poem describing how India began her dialogue with other civilizations in pre-historic times. In brisk cadence he wrote –

Here came Aryans, Non-Aryans,

(HethayArjyo, hethayAnarjyo)

Dravids, and Mongols

(HethayDrabir Chin)

Tribes of Sythians and Huns

(Sakh Hun dol)

Pathans and Moghuls

(Pathan Moghul)

In one body they merged

(Ekdehehololeen).

And finally:

They came to take and will stay to give

(Debey aarnebey, melabeymilibey,)

But they will never leave

(jabenaphire)

Bharat the seashore of humanity

(EiBharatermahamanbershagartirey).

This then was Gurudev’s message of India over five millennia of recorded history. The intermingling of many racial strains is written in the genetic code of her people, in their varied aptitudes and gifts. India has given sanctuary to people fleeing religious persecution—Zoroastrians and Bahais from Iran, Jews from Spain and Portugal, Christians from Armenia, refugees from political persecution in Afghanistan.

There has been no clash of civilizations in India. She has a talent for assimilation and innovation. In the midst of invasions and turmoil there was a continual and enriching dialogue between various groups. They have lived with their own identities and have become part of the great Indian tapestry.

On the 160th birth anniversary of the greatest Indian of our times, it would be well for all Indians to remember and abide by this message.

Achala Moulik is a retired IAS officer, cultural historian, novelist, Pushkin Medal awardee and author of “Rabindranath Tagore, the Universal Man”.