Australia knew its strained relations with China were on the turn last week when visiting Chinese Premier Li Qiang offered to send a new pair of pandas for Adelaide’s zoo. Pandas are native to China and since its founding in 1949, the People’s Republic has used this rarest member of the bear family and among the world’s most threatened animals as goodwill ambassadors. When the Soviet Union celebrated the 40th anniversary of the October coup which brought about Lenin’s Soviet regime, Mao Zedong gifted Moscow with a panda called Ping Pong. Fifteen years later, when US President Richard Nixon made his historic visit to China, Beijing gave the United States two pandas, Ling Ling and Hsing Hsing. This was a clear sign of a normalisation of the relationships between the two countries, and marked a pivotal moment in China’s foreign policy. So what happened on Sunday to lift Australia into this distinguished league?

Ties between Australia and China began a downward spiral more than six years ago when Canberra accused Beijing of meddling in its domestic affairs, an accusation that started a series of diplomatic and economic spats. Australia is home to a large Chinese diaspora of about one and a half million, more than 5 per cent of the population, and for years there had been allegations that China’s sinister United Front, which had operated to consolidate the Communist Party’s control over the restive regions of Xinjiang and Tibet, was now carrying out influence operations among the diaspora. As a result, in 2018 Canberra passed a new law against foreign influence and espionage, which was quickly followed by the ban on China’s Huawei from building the country’s 5G mobile network. Australia was among the first countries to do so, citing national security.

Suddenly Covid came along and the atmosphere between the two countries worsened further after the then Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison called for an international enquiry into the origins of the coronavirus that caused the outbreak. Beijing has always been super-sensitive to any accusation of culpability for the virus that devastated many parts of the world, rejecting all calls for an independent investigation into the cause of the outbreak. Morrison’s push created huge anger in Beijing, not only because it was seen as a slight against Chinese sovereignty, but it was also a sign of his government’s willingness to echo and coordinate with US President Trump’s anti-Chinese campaign. Then, as China’s “Wolf Warrior” diplomats became even more combative, a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman tweeted an edited image of an Australian soldier holding a knife to the throat of an Afghan child, a barbed reference to an ongoing war crimes probe. Relations between Australia and China reached rock-bottom.

All this led to significant trade issues between the two countries. China is Australia’s top trading partner by far, and although the overall impact was relatively small, some sectors were badly hit. China slapped crippling tariffs on Australian barley; imposed massive levies on Australian wine; halted the import of cotton and lobsters; banned timber exports, and held up more than 50 Australian coal ships that subsequently became stranded off China’s coast. The latter proved to be an own goal by Beijing as it led to power blackouts across the country with hundreds of millions of Chinese people having their electricity rationed – an irrational overreaction by an angry Xi Jinping.

Now the “twists and turns” in Australia-China relations are over, according to China’s second-most powerful leader, Li Qiang, during the first visit of a Chinese premier to Australia since 2017. Li was welcomed last weekend by Australia’s foreign affairs minister, Penny Ying-Yen Wong, who was born in Malaysia to a Chinese-Malaysian father and an English-Australian mother. Wong is the first Asian-Australian in an Australian cabinet and is considered by many to be the most trusted politician in the country. In her welcoming speech, Wong said that Li’s visit was “the result of two years of very deliberate, very patient work by the government to bring about a stabilisation of the relationship”. She noted, however, that tensions remained as Australia is “in a permanent contest with China over the Pacific”. That includes China’s attitude to Taiwan, which Wong called “one of the riskiest flash points in the world”.

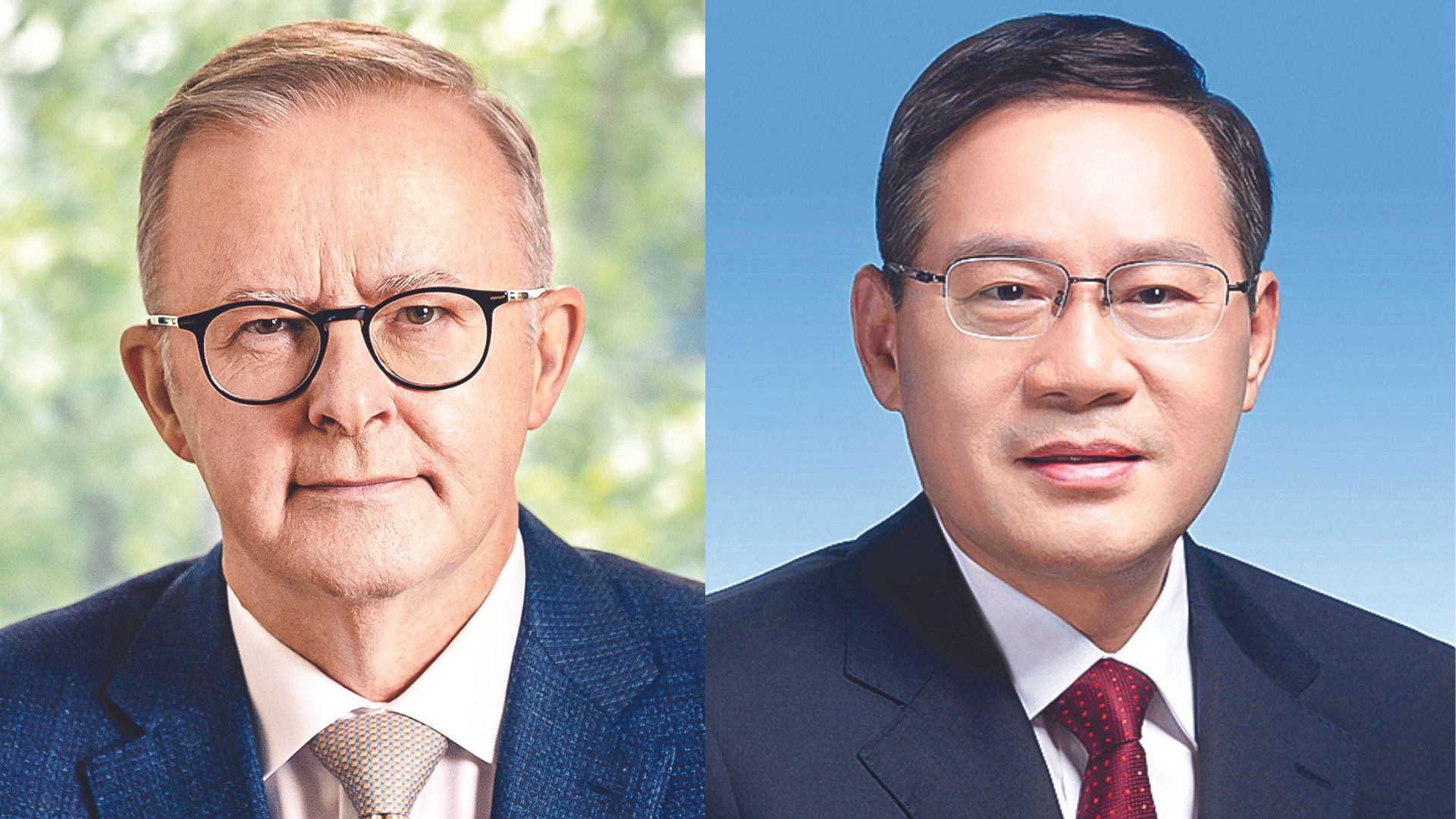

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese also hailed the improvement in ties with China when he hosted a reception for Li Qiang, declaring that the nations had “renewed and revitalised” their relations after years of turmoil. However, neither appeared starry-eyed about the relationship, which, according to Li was “essentially characterised by mutual benefit and results”. “Prime Minister Albanese and I had a candid, in-depth and fruitful meeting and reached a lot of consensus”, he added, as officials signed new cooperation agreements on trade, education, climate change, culture and intellectual property. Seasoned diplomats interpreted Li’s carefully constructed comments to indicate that there had been sharp differences on both sides. Albanese had raised concerns about the suspended death sentence handed to jailed Chinese-Australian academic Yang Hengjun for alleged espionage, about continued interference by Chinese agents in Australia, and Beijing’s support for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Last November, Albanese blasted the Chinese military’s conduct as “unsafe and unprofessional” after they had fired dangerous sonar pulses at Australian naval divers off the Japanese coast. He also rebuked Beijing again last month when a Chinese fighter jet dropped flares near an Australian navy helicopter enforcing international sanctions on North Korea. During Li’s visit, Albanese claimed that he had taken a “patient, calibrated and deliberate” approach to relations with China and was pursuing “constructive dialogue in a mature way, of trying to work through where there are differences”.

In recent years, Australia has managed to weather China’s sanctions thanks to a surge in global commodity prices. Australian iron ore and lithium, a critical ingredient in electric vehicle batteries and core to Beijing’s new technology drive, continued to flow to China, earning Canberra A$1.2 billion and preserving Australia’s economic resilience. China buys a third of Australian exports and supplies a quarter of its imports.

Some observers question Canberra’s strategy of not just restoring but expanding trade with Beijing at a time when security rifts in the Indo-Pacific region are deepening. Trade with China reached the highest ever level last year of US$ 145 billion at the same time that Canberra increased spending on defence as it has pushed ahead with the Quad security grouping with India, Japan and the US, as well as the AUKUS security alliance, in response to China’s increasingly aggressive behaviour. So how can Canberra square the circle of building economic relations with a country it sees as a threat? It’s “cakeism”, said a former Australian government official. “We want a full-throated military deterrent to China but desperately still want access to that market for our iron ore and wine”, he said.

In the meantime, the two pandas on loan from China, Fu Ni and Wang Wang, both nearing 20 and the only giant pandas in the southern hemisphere, have failed to breed in more than a decade in Adelaide zoo. They will soon be on their way home and replaced by a new duo, as promised by Li Kiang. Call it Panda diplomacy or a distraction from the great power rivalry in Asia, either way it’s a clear sign that Australia is back in China’s good books.