The Indo-Greek (Yavana) Kingdom produced illustrious statesmen and military commanders, such as Seleucus I Nicator, Menander I Soter (Milinda), and Demetrius III Aniketos (the Invincible).

New Delhi: In recent years, there have been several initiatives to recover or reappraise India’s indigenous strategic thought and statecraft, especially in ancient times. Such an endeavour requires not only a careful scrutiny of a variety of sources and evidence, but also an exploration of the ways in which the models of political and military leadership that emerged in the Indian subcontinent interacted with exogenous factors.

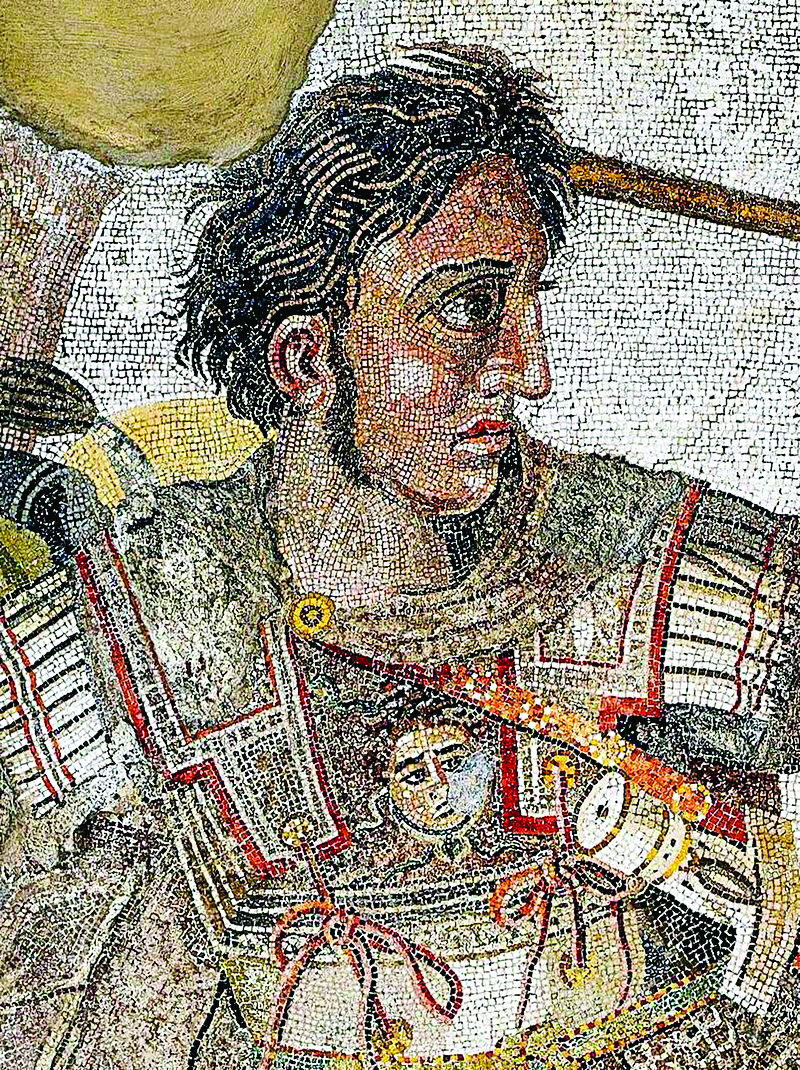

Alexander’s expedition to India served as the fulcrum for Greek influence, led to the proliferation of Greek settlements, and gave new impetus to trade. It incubated the amalgamation of Greek and Indian civilizations, a powerful manifestation of which is the Gandhara school of art. One could claim that the operations of Alexander’s army and the Battle of Hydaspes (326 BC) against King Porus’ forces, which signalled the end of Alexander’s advance, were a source of lessons in military strategy that spurred the growth of the Mauryan Empire and inspired Kautilya’s seminal treatise on statecraft, the Arthashastra. The Indo-Greek (Yavana) Kingdom produced illustrious statesmen and military commanders, such as Seleucus I Nicator, Menander I Soter (Milinda), and Demetrius III Aniketos (the Invincible). Seleucus was defeated by Chandragupta Maurya in 305 BC. He agreed to a truce that involved a marriage alliance between Helena, Seleucus’ daughter, and the Indian ruler. Unlike another legendary Greek female figure with a similar-sounding name, Helen of Troy, who was associated with the Trojan War, one of the biggest wars in Greek mythology, Helena ushered in a period of peaceful symbiosis of the Seleucid and Mauryan dynasties. A number of Greeks were sent as emissaries or were appointed envoys to the Indian emperors and left accounts of the inner workings of the Mauryan state. One of such narratives is the Indica, which was written by Kautilya’s contemporary, Megasthenes, Seleucus’ ambassador to Chandragupta’s court in Pataliputra, and has survived in the form of quotations by later Greek and Roman authors.

Alexander’s campaign and the creation of the Indo-Greek Kingdom heralded a long phase of physical encounters between the Indian and Greek civilizations. Greek thought and science remained a constant element in the history of pre-modern India. The consolidation of Islamic rule facilitated the influx of scholars and scientists from various parts of the Islamic world who were steeped in Greek learning. It also contributed to the circulation of political and moral advice literature, such as the Akhlaq-i Nasiri (Nasirean Ethics), the magnum opus of the 13th-century Persian polymath Nasir al-Din Tusi. The Nasirean Ethics is a compilation of ideas and dicta derived from Greek sources, particularly Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics and partly Plato. It expatiates upon the virtues related to individual conduct (ethics), the management of the household (economics), and the government of the political community (politics). The diffusion of Tusi’s thought in the central and eastern lands of Islam was given a boost by the Akhlaq-i Jalali (Jalalian Ethics), an expanded version of the Nasirean Ethics, composed by Jalal al-Din Dawwani, a distinguished religious and legal scholar, in the 15th century.

One of the first akhlaq sources dedicated to the Mughals is the Akhlaq-i Humayuni (Ethics of Humayun), which was addressed to Babur, after he took over Kabul in 1504. The Ethics of Humayun contain a set of maxims about good government that had a deep and lasting impact on the leadership styles of the first Mughal rulers in the context of running a far-flung and complex imperial polity. But it was in Emperor Akbar’s time that Tusi’s Nasirean Ethics evolved into one of the truly foundational texts of Mughal political culture. Akbar, arguably the most brilliant strategist of the Mughal dynasty, was so captivated by the Nasirean Ethics that he, being dyslexic, had it read to him by his courtiers on a regular basis. Most probably, the Mughal Padishah saw in Tusi’s treatise a comprehensive yet handy, easily digestible blueprint for effective political conduct and policy-making. Akbar prescribed it as a must-read for Mughal government officials and military commanders. One could go far as to hypothesize that the philosophical tenets enshrined in Tusi’s oeuvre underpinned Akbar’s grandiose project to build Fatehpur Sikri (City of Victory) as the new capital of the Mughal Empire and his vision of sulh-i kul (absolute/universal peace).

Similarly, the Ain-i Akbari (Institutes of Akbar), the famous gazetteer of Akbar’s reign composed by his grand vizier (prime minister) Abu’l-Fazl is imbued with Greek teachings, as transmitted by akhlaq writers. Intriguingly, Abu’l-Fazl drew upon yunani medicine and the humoral theory of the Greek physician

Akhlaq works were best sellers not only in the Indo-Islamic world, but also in other regions of Islam. Abu’l-Fazl’s rough contemporary in Istanbul, Kınalızade Ali Çelebi penned the Ahlak-ı Alai (Sublime Ethics/Ethics of Ali) that was destined to become one of the major sources of Ottoman political discourse. The akhlaq genre and its variants remained one of the prevalent modes of writing about politics until the first half of the 20th century, as evidenced by a corpus of Urdu texts that discuss topics reminiscent of Tusi, Dawwani, and the Greeks. Copies and Urdu translations of Dawwani’s Jalalian Ethics were printed in the 19th century in Lucknow, Kanpur, and other cities, and a solid English translation appeared in Lahore in 1939. The akhlaq retained its appeal even beyond the realm of Islamic ethics: Hindus, who attended madrasas for administrative training, imbibed the spirit of the Greek classics by engaging in the study and interpretation of akhlaq manuals and advice literature in Arabic and Persian. Henry George Keene, who worked for the East India Company and later taught Persian and Arabic at the East India Company College in Haileybury, published in 1867 an English translation of the Akhlaq-i-Muhsini (Muhsinian Ethics), a distillation of earlier akhlaq doctrines by the 15th-century Persian literatus Husayn Wa‘iz Kashifi, who also produced a collection of didactic tales and fables in Persian based on the Kalila wa-Dimna and, by extension, on the Panchatantra. Keene’s translation was integrated into the College’s educational program for the administrators of the East India Company.

* Prof Vasileios Syros is a Distinguished Fellow at the Centre for Military History and Conflict Studies at the United Service Institution of India (USI).