NEW DELHI: The underlying causes of Sheikh Hasina’s rise and fall show that the future is likely to be precarious.

The lyrics of one of the most popular songs of the Bangladeshi Hindu singer Rahul Ananda says, “Someone else’s place, someone else’s land, and yet I have built my house upon it, and call it my own”. On YouTube, this Bengali song has 43 million views.

Ananda led the popular band Joler Gaan and lived for years in a 140-year-old house which he had filled with countless musical instruments he constructed and procured, more than 3,000 of them. The house stood in Dhanmondi, close to the old home of the founding father of Bangladesh, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, which had been turned into a museum. If Rahman’s house was a tribute to the much-loved leader, who was assassinated in 1975 by rebel military officers, Ananda’s house celebrated a shared heritage of Bangla music enjoyed by seemingly everyone in the country.

Perhaps not everyone, though. Islamist mobs burned down Ananda’s house, and the Mujibur Rahman Museum, after Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina fled the country following months of mass civil unrest led by first by students and then with mass participation of Bangladesh’s notorious Islamist groups including the banned Jamaat e-Islami which has legacy ties with Pakistan’s spy agency, ISI. The destruction of Ananda’s home occurred even though he had supported the uprising against Hasina and was a prominent “secular voice” in the country who was known to have, as Bangladeshi newspapers noted, maintained “an open home” for everyone.

Ananda and his family had a narrow escape from the mob, and are now in hiding. Their story is emblematic of what Professor Abul Barakat of Dhaka University described as an “exodus” in 2016 pointing to the constant decline in Hindu population in Bangladesh for more than five decades. Barakat predicted that at this rate, in only about 30 years or so, there would hardly be a Hindu left in Bangladesh. According to Barakat’s calculations, since 1964 and till 2013, more than 11 million Hindus had left Bangladesh.

And yet, one of the accusations against Sheikh Hasina, who led her Awami League party to rule the country since 2009, was that she was favourable towards Hindus. This was an accusation frequently flung at her especially by the Jamaat and other radicalized hardline Islamist groups like the Hefazat e-Islam. This despite the fact that as late at 2022, in a major Islamist mob attack on Hindu temples, including the ISKCON temple in Bangladesh, several people were killed. More than 91% of Bangladeshis are Muslim, with less than 8% Hindus, and some small numbers of Christians and Buddhists.

On her part, at least in proclaimed policy, Hasina tried to present the case for a secular Bangladesh, a cause which was dear to her late father too, including presenting the idea that people’s “religions might be different, but festivals are for everyone”. There was a much-promoted scheme that offered small amounts for money to assist Durga Pujas around the country. But the fundamental truth never changed for the Hindus—they had been, were, and are excluded from any real progress Bangladesh had made, even under Hasina.

A study called “Assessing Poverty and Deprivation of Religious Minority in Bangladesh: A Study on Hindu Community” done in 2022 by two sociologists of Jagannath University in Dhaka, Ashek Mahmud and Md. Rafiqul Islam, noted that Hindus not only faced “low intensity hostility at all socio-economic levels, including the state” but a majority of them could be categorized as poor.

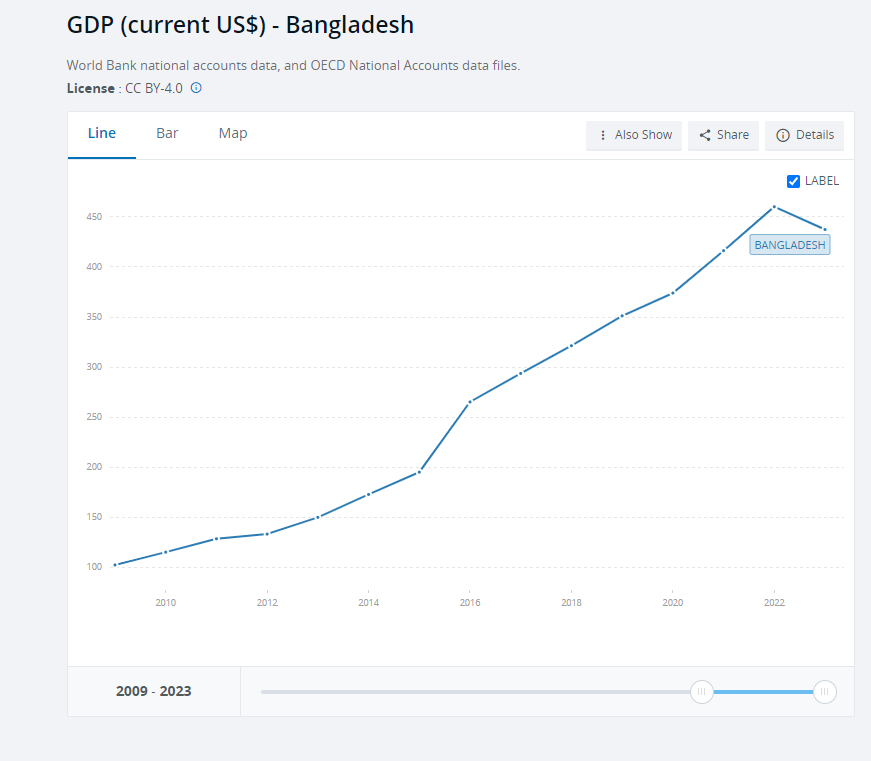

This, even though, under Hasina Bangladesh saw rapid economic growth and rise in social indicators which put it in line to leave behind the LDC (Least Developed Country) status by 2026. The country’s GDP grew at an average of more than 6% ever since Hasina came to power in 2009, which is higher than the average of the Asia-Pacific region during the same time. Hasina’s interventions made electricity near ubiquitous in a country once notorious for power cuts. Bangladesh’s famed textile sector—employing 80% women—ballooned to a global garments powerhouse worth nearly $50 billion in exports. In 2021 and 2022, Bangladesh exported around 20% of all cotton T-shirts in the world.

This has a direct socio-economic impact. The researchers Rachel Heath and A. Mushfiq Mobarak pointed out in a 2014 National Bureau of Economic Research working paper titled “Manufacturing Growth and the Lives of Bangladeshi Women” that “…access to factory jobs allows young girls in Bangladesh to delay both marriage and childbearing in statistically and quantitatively significant way. These results could be explained by families choosing to postpone their daughter’s marriage and childbirth so that either (a) she can to work in factories, or (b) she can invest in schooling at an early age to have a better shot at high-paid garment sector work later in life, or (c) because the adults in the household now have better paid factory jobs, and the family is wealthier and can afford to invest in child quality, and keep young girls in school rather than marry them off”. In one of the most densely populated countries in the world, fertility rate fell to 1.9, well below replacement rate.

Under Hasina Bangladesh’s per capita GDP surpassed India’s. Bangladesh’s social parameters had been steadily improving, and during Hasina’s term, life expectancy and infant mortality hit unprecedented levels. In the last five decades, Bangladesh’s life expectancy rose by 50% and infant mortality declined by nearly 90%.

From barely around $300 million when she came to power, Hasina’s policies including her push of “Digital Bangladesh” took the information technology-related sector to more than $1.5 billion.

Hasina had been plagued by the violent climate of her country ever since she came to power. Only months after she came to power, a group in the paramilitary Bangladesh Rifles revolted against their superiors which was widely seen as perhaps targeted at destabilising the Hasina government. Between 2013 and 2016, the Hasina government conducted trials of war criminals including several from the Jamaat accused of mass violence, and murder during the battle for independence in 1971, and for aiding and abetting the worst atrocities of the Pakistani army trying to prevent Bangladesh from breaking away. But she had to accommodate another virulently hardline group called the Hefazat e-Islam. In fact, some of the draconian restrictions on social media that the Bangladeshi young so objected too, and the constant state monitoring, came from intense pressure from Islamist groups who claimed that Hindus were writing denigrating social media posts against Islam.

Bangladeshi politics had always been violent and authoritarian, and Hasina did to her rivals what they had done to her and her family, including putting her more ardent rival, Khaleda Zia behind bars. In Bangladeshi politics, Zia and the Islamists have been known to be close to Pakistan and allegedly the ISI, while Hasina, to India, which sheltered her and her sister after the assassination of Mujibur Rahman and the rest of the family.

Some of the strongest accusations against Hasina from her detractors was about this issue, and instances like the death of a student called Abrar Fahad, who died in 2019 after allegedly being thrashed by student activists of Hasina’s Awami League party.

Perhaps growing economic prosperity could have still ensured peace and calm but for the fact that the Covid-19 pandemic, followed by the global downturn, and then the hit

Bangladesh already had one of the lowest minimum wages in the world, and so acute was the problem that a clutch of companies including Adidas, Levi Strauss, Under Armor, Patagonia, Puma, Hugo Boss and others wrote a letter to Sheikh Hasina appreciating “…the value that Bangladesh holds as the third largest supplier of garments as well as a fast growing supplier of footwear and travel goods to the world” but cautioning that minimum wages had to be urgently raised.

Workers had been demanding a significant rise in the minimum wages, but the wage board of Bangladesh controlled by garment factory owners refused to relent and only offered a small raise.

The only truth about authoritarianism is that, for a time, only material prosperity might make it bearable. But the confluence of many forces finally shifted the needle firmly against Hasina. No amount of police force could control the flames. With reflection, it is easy to see that in a sense Hasina is as much a victim of Bangladesh’s long and violent history of toxic power grab and religious persecution as she is the perpetrator. The balancing act she tried to play could only be maintained for a while due to strong economic growth leading to some qualitative betterment of life, and infrastructure, and institutional muscle power.

But the forces she took on, for instance, the Jamaat-e-Islami, have deep and growing roots in Bangladesh. Foreign assistance, including from extremist groups in the UK, have poured in to create groups like Hefazat, which was created by hardline clerics only a few years ago to expressly oppose Hasina’s push for a secular nature to Bangladesh. As the murder of the secular publisher Faisal Arefin Deepan in 2015 showed, no matter who was in power, the most blood-soaked streets were controlled by the Islamists. The strategic location of Bangladesh in the Bay of Bengal also meant constant international pressure as the Indian Ocean Region became more and more fraught with geopolitical tension.

None of these issues will go away and it is not easy to see how Nobel Laureate Muhammad Yunus’ arrival, once again, to pitch for peaceful politics without religious bias would take root in such an environment. Yunus, and his work in the Grameen Group, has well-wishers in Bangladesh and around the world, but he does not control the streets and a lot would depend on whether the Bangladesh Army would help him control the streets.

Hindol Sengupta is professor of international relations at O. P. Jindal Global University, and co-founder of the foreign policy platform “Global Order.”