The Naval uprising of February 1946 shook the foundations of the British Empire and hastened the transfer of power to liberate India, but the political leadership never gave the ratings their due.

BENGALURU: India’s freedom movement is an ever green field for historians, researchers, academicians and students. Tucked away into obscurity in the pages of history are movements, moments and their heroes who liberated India from the Imperial clutches, who are yet to be recognised as national heroes.

The Naval uprising of February 1946 is one such movement that shook the foundations of the British Empire and hastened the transfer of power to liberate India.

HMIS Talwar, a training establishment of the Royal Indian Navy (RIN) in Bombay, hit the headlines, when on 18th February 1946, 1,500 ratings stormed out of the mess refusing to have breakfast, because the quality was poor and quantity was inadequate. An uproar filled the air, in no time Quit India slogans rocked the establishment. Protest for jam and butter was only a ruse for a larger mission. The ratings had become the instruments to India’s freedom, to change her destiny. It was as if they were completing the unfinished task of the INA.

The foundation for this protest was set on 1st December 1945, when HMIS Talwar was to be opened to public for the Navy Day celebrations. On the previous night, B.C. Dutta, a rating in the communications branch, along with a few confidants stealthily wrote slogans on the wall. Brooms strewn around, burnt flags, buckets and “Quit India”, “kill the white dogs” slogans greeted the commanding officer and guests the next morning. The operation was so well executed that no arrests could be made.

Every day, Quit India slogans appeared on the walls of HMIS Talwar, the unit’s vehicles and on the commander’s car. This brazen defiance could not be contained, the perpetrators could not be found.

Emboldened by their success on the Navy Day celebrations, the ratings waited for an occasion to show a bigger demonstration of defiance. The commander in chief’s visit to Talwar on 2nd February 1946 was greeted with posters of anti-British slogans on the walls. This time Dutta was not lucky; a gum bottle that he had used was a giveaway. He was arrested and sent to solitary confinement. Dutta’s arrest further kindled the fire in the ratings.

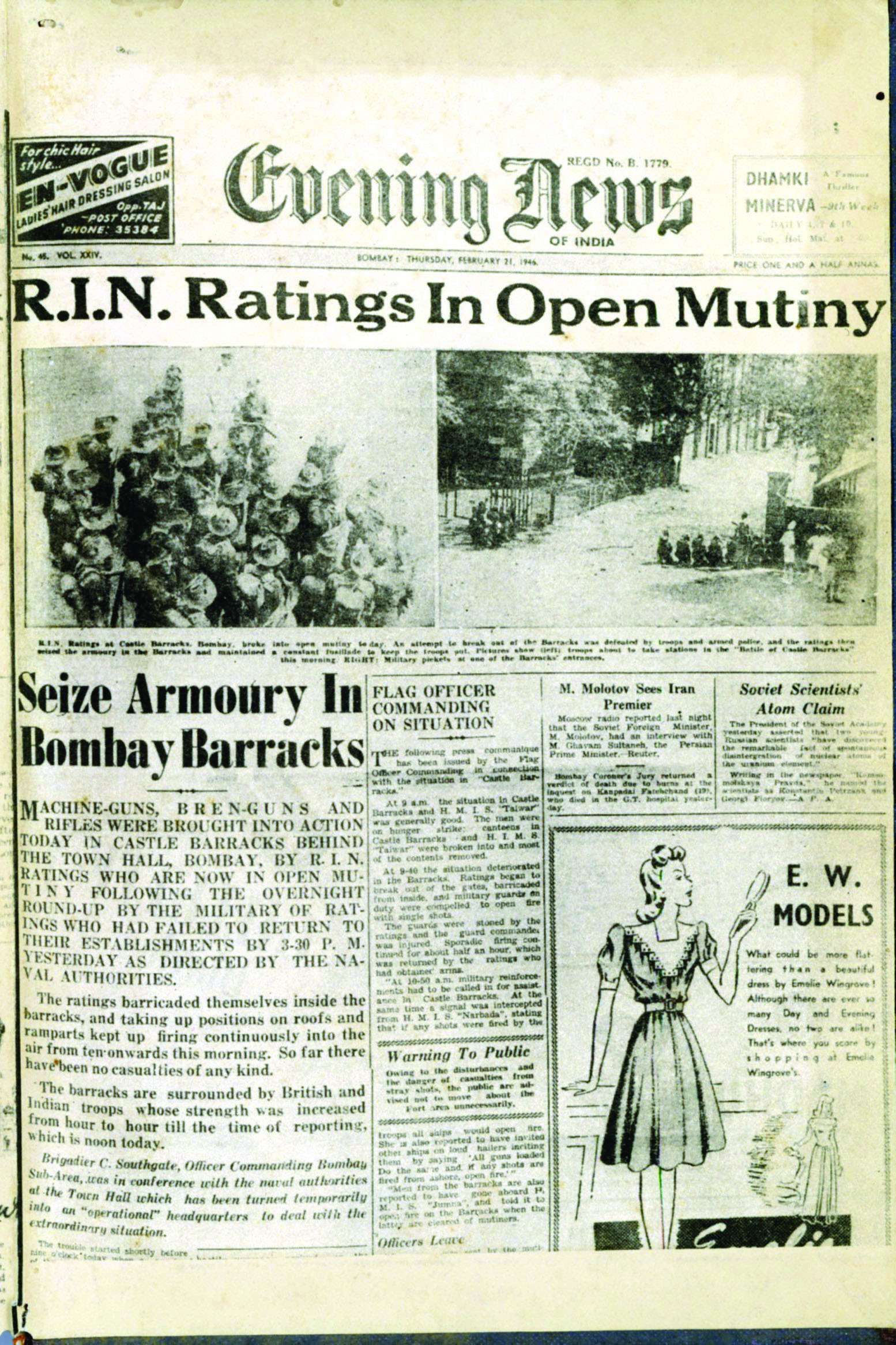

The 18th February incident opened the gates to a mass uprising in the RIN. The ratings used the ship’s telegraphic sets to send messages to other ships and establishments. Some ratings entered Castle barracks adjoining the dockyard and raised anti British slogans. Hundreds of ratings from Castle barracks joined in. What ensued was a full blown protest defying British authority. The ratings had taken control of the armouries at Castle barracks.

By 20 February 1946, the RIN was in open revolt against the British. For too long the ratings had endured humiliation and discrimination by their British masters, who generously abused them with filthy epithets. While out at war, the ratings had learnt about the heroic sacrifices of INA and they began to question themselves and their loyalty for the country; whose war were they fighting?

20,000 ratings lay siege to 78 warships in the ports of Bombay, Karachi, Madras, Vishakhapatnam, Calcutta, Cochin, and Andamans; nearly all the shore establishments were under the control of the ratings. The Union Jack was hauled down and the Indian Tricolour was hoisted over the ship’s masts. Soon, Indians in the Royal Indian Armed Forces in Bombay, Jabalpur and Madras, Army infantry and Air Force stations joined the uprising.

Six lakh mill workers in Bombay took to the streets in support of the Naval ratings; civilians and students all over the country joined in. Hundred thousand workers in Calcutta struck work, trains were held up.

The British panicked and pulled out their battle tanks and armoured vehicles to quell the protestors. The ratings geared up for self-defence, they lowered the ship’s guns and prepared the ships for “action station”.

Armed military guards surrounded HMIS Talwar and Castle barracks. Food supplies and water were cut off; a vindictive British wanted the ratings to starve to death. The seafront around Gateway of India was chock-a-block with people carrying food packets and pails of water for the ratings. Indian soldiers helped load the food on boats to be reached to the ships at the harbour. At HMIS Talwar and Castle barracks food packets were sent over the high walls.

Britain had lost the loyalty of Indians in their defence services, the very backbone of their existence and power. In desperation they began using ammunitions on civilian protestors and ratings. In four days, 270 had died and 1,300 injured. Vice Admiral Godfrey declared that if the men on strike did not submit, the government will not hesitate to raze the Indian Navy to ground and that he would be proud of it. On February 24, HMS Glasgow, a six-inch gun cruiser of the Royal Navy and two HM destroyers arrived at Bombay; heavier combat units were positioned around, ready to be brought in. The plan was to bomb all the ships at the harbour.

France called the uprising as a death knell for the British. In Jhansi Nehru said, “the whole country is sitting on a volcano”.

BRITAIN PANICKED

The mutiny, as the British called it, caught them off guard. Their Naval commanders miscalculated and mishandled the situation. In mid-February 1946, Gen Auchinleck had foreseen hostile action, he had feared civil war where the armed forces would join the rioters.

On 27 February 1946, Sir Colville in his correspondence to Lord Wavell discussed the uprising. Attlee quickly understood the implications and began discussing transfer of political power with the Indian leaders. The MPs’ delegation had told him, “there are two alternative ways of meeting this common desire (a) that we should arrange to get out, (b) that we should wait to be driven out”.

On the night of 23 February 1946, the British Cabinet held an emergency meeting. By March 1946 they were discussing the modalities of the framework of governance. Lord Wavell was recalled and Lord Mountbatten was brought in. Wavell said to Mountbatten, “I have only one solution, which I call ‘Operation Madhouse’—withdrawal of the British, province by province, beginning with women and children, then civilians, then the Army. I can see no other way out.”

The Naval uprising was the last nail on the coffin of British authority in India.

Mountbatten was sworn in on 24 March 1946. On 2 May he sent a proposal to London for Transfer of Power. On 17 May he held a meeting with the Indian political leaders at Delhi. On 3 June AIR announced the Transfer of Power and Mountbatten announced this on 4 June at a press conference.

18 months after the uprising India became independent.

RATINGS SURRENDER

The ratings had become the banner of Indian revolt against British occupation, they were proud that they had gained control over the RIN and converted it into the Indian Navy; they wanted to hand it over to the political leaders to take control. Freedom was inching closer. The ratings were looking forward to a leader like Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose to lead them.

However, their dreams were shattered. The national leaders condemned the uprising and refused to lend any support

The ratings were compelled to surrender, but not without standing their ground. Among their demands were the release of all INA and political prisoners, withdrawal of troops from Indonesia and the promise that they would not be victimized.

India’s political leaders failed to protect the ratings after their surrender. Britain did not keep its promise and the ratings were removed from service. Thousands of them were rendered jobless. Post partition, Jinnah absorbed all the ratings in Pakistan into the Pakistan Navy.

The Naval ratings were punished for converting the Royal Indian Navy into the Indian Navy. History is yet to accord them due recognition as national heroes.

The Indian Navy, however, has recognized their services with pride. An impressive Naval Uprising memorial at Colaba celebrates the sacrifices of the ratings; their names are etched on the granite walls to remain for posterity.