In 2021 I travelled to Beijing from America to start working for the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. I went there at the very height of the Covid-19 pandemic— in America and the world—when the virus was ravaging the populations of country after country, vaccines were only beginning to be distributed globally and about 5,000 Americans were dying from the disease each day.

Based on official statistics from the Chinese government, there were no more than a few dozen documented cases of the virus in China at the time. This was the result, it claimed, of a year of draconian policies forcibly restricting travel, locking down cities and towns, testing literally millions of people in a matter of days, and contact tracing where outbreaks had occurred as only the Chinese government can do.

The contrast between how the two countries had addressed the pandemic could not have been more stark—particularly considering that China has four times the population as the US. It therefore made perfect sense to the government of China that all individuals arriving from outside the country would spend three weeks in quarantine in another city before being allowed to travel to Beijing, for example.

This was not the “voluntary” quarantine that some states in America had toyed with over the course of 2020. A year after the pandemic had broken out, the American government’s horribly botched and feeble effort to address the virus was only just starting to change following the election of Joe Biden.

I was not happy to have to admit that Americans had really brought their absurd degree of suffering on themselves, the result of a combination of the Donald Trump administration’s inexcusably bad response to the pandemic in combination with so many Americans’ pigheaded approach to taking basic precautions to protect themselves—and others— such as wearing face masks and social distancing. Until the day I departed, I continued to witness some of my fellow Americans either not wearing masks or failing to do so correctly. This was mystifying to me.

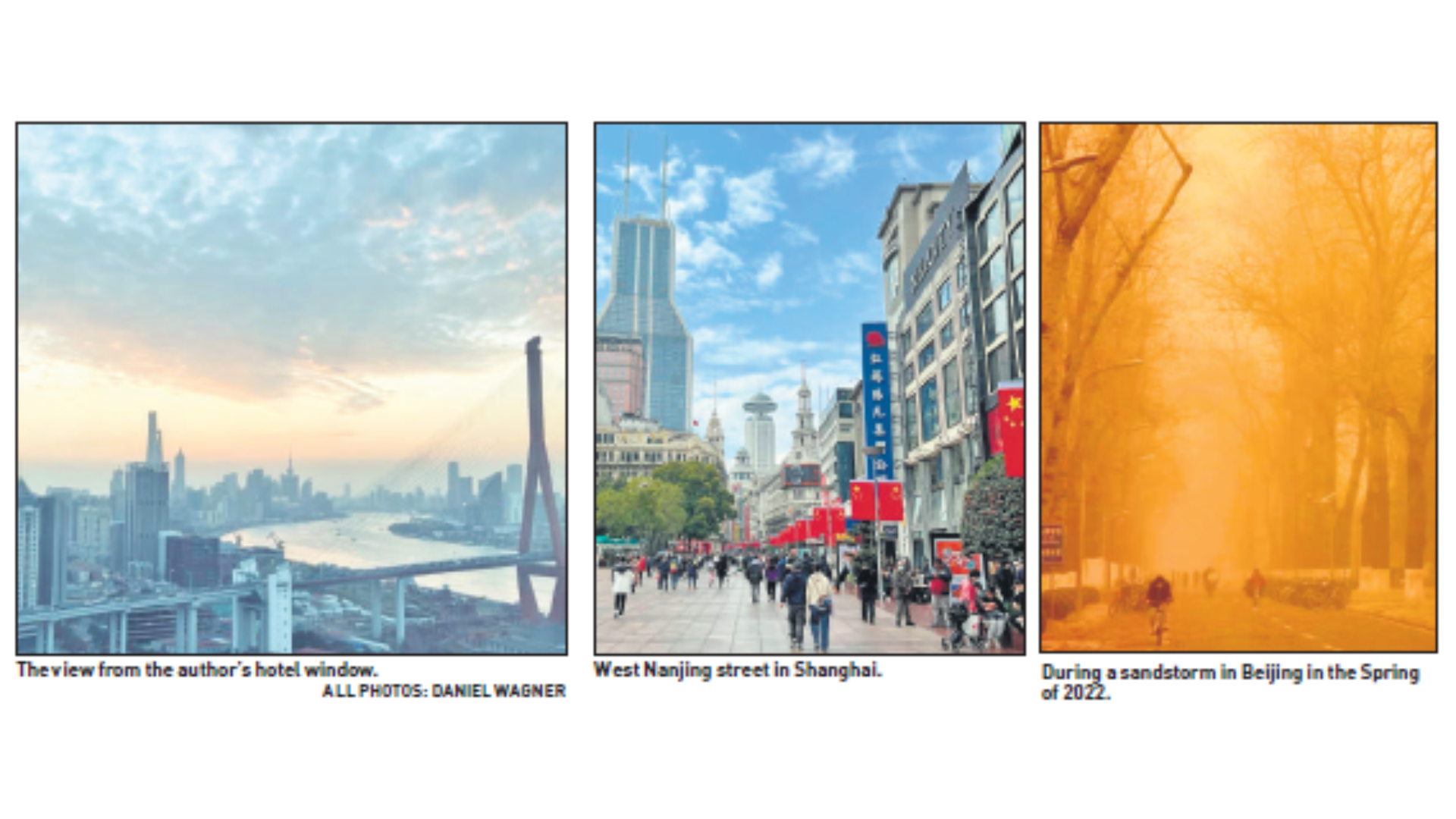

It took many Americans an entire year of having the importance of wearing masks drilled into their heads by a constant assault from the media in order for the wisdom of doing so to finally start to sink in. But tens of millions of Americans refused to do even that. My quarantine was no picnic. Though billed as 4-star, my hotel was really more like 3-stars. My standard room had two twin-size beds, one of which had no sheets on it when I arrived, for some reason. At least it had a nice view of the river and city, when the air was not so polluted that they were difficult to see.

I was to spend 14 days there without the ability to leave my room, complete with bad hotel food and a terrible Internet connection. I had to jimmy-rig signal from adjacent rooms, because, despite repeated attempts to get the WiFi router in my room to work—including having it replaced—it would not. My body temperature was taken electronically twice a day and my food was delivered (nearly always cold) by young men and women wearing hazmat suits, who sometimes rang the doorbell to let me know it had arrived and sometimes not— meaning the food would then be ice cold by the time I opened the door to see if it had arrived.

Although some would argue that such a draconian approach to Covid-19 management is exactly what the US desperately needed at the time, it would never work, much less be attempted there. Americans treasure their basic freedoms— including the freedom to be just as stupid as they want to be—even if that means the freedom to do harm to themselves and others in the process. I covet my personal freedom as much as the next guy, but I draw the line when individual freedom negatively impacts the health and lives of others.

Many Americans never seemed to understand that, nor cared that they didn’t. There was no need to have a “minder” outside my door or anywhere else in my hotel. Apart from the fact that I had no intention of stepping a foot outside my hotel room door for two weeks, all the halls, stairwells, and elevators were electronically monitored and the elevators were blocked without a key card.

Big Brother is everywhere in China and Chinese citizens are well aware of the government’s ability to keep tabs on their every movement. I was even instructed to drop chlorine pills into the toilet every time I had a bowel movement in an attempt to kill the virus before flushing. The numbers of “official” cases of Covid-19 in China were mind boggling—zero cases in all of Beijing, 3 cases in Shanghai, a couple here, several there. Having come from America at a time when 350,000 Americans were reported infected on a daily basis, I felt something had to be wrong with China’s reporting protocols. Having witnessed the behaviour of China’s own Covidiots, it made even less sense.

I wondered, are the Chinese authorities that good or was it all just part of the government-driven narrative about what a good job it had done beating down and then controlling the virus? I came to realize that the Chinese government really is that good. When the Delta variant of Covid-19 erupted in Nanjing in July 2021, I was able to witness the government “machine” in action.

The summer of 2021 coincided with the most serious outbreak (of the Delta variant) of Covid-19 seen since it began in 2019. An airplane cleaning crew in Nanjing apparently caught the virus by being unprotected while cleaning an Air China flight from Russia. It quickly spread from the airport, of course, and within a couple of weeks had impacted dozens of Chinese cities, including Beijing.

In Beijing, just two recorded cases prompted the government to take steps that culminated in shutting the place down. I had planned to visit Chengdu for a long weekend, but many forms of public transportation in and out of the city were cancelled, just days after the outbreak began. Imagine— a city of 22 million sealed off because of 2 documented cases of Covid-19. It was fascinating (and instructive) to see the wheels of China’s mammoth state apparatus at work to manage the Delta outbreak.

With precision, the government issued mandate after mandate, which were dutifully followed by the population. One of my friends from Beijing happened to be in Wuhan when all the residents in the city (11 million of them) were ordered to get tested. He said the streets emptied and people lined up, dutifully. It only took a few days for all the tests to be administered.

Nanjing was shut down. Rail, bus and air traffic throughout the country was curtailed or eliminated to or from medium or high risk destinations. People did what they were told and didn’t question it. The government speaks and citizens fall into line—a great contrast, of course, with the freedom of choice that exists in many other parts of the world. But China succeeded in controlling it while few other countries (with the exception of New Zealand, that took the same approach) did.

That speaks volumes about the potential benefits of having a one party dictatorship and no freedom of speech when pandemics or natural disasters hit—they can be effectively managed. Subsequent outbreaks in Hong Kong, Shenzhen and most recently, Shanghai, resulted in the same protocols being implemented.

With 25 million residents, Shanghai received the most attention, and rightly so. In China, all most Chinese would know is that the virus is being successfully eradicated, even though infections rose to some 25,000 new cases per day—during the lockdown. That is because most do not have access to a VPN so only know what official state media tells them. The rest of the world knew that food and medicine shortages plagued the city and that many Shanghai residents were very upset about being locked up for weeks on end.

The economic consequences to Shanghai, China and the world because of its dependence on China through the global supply chain are significant. I had hesitated to get vaccinated while in China because I had a pending visit back to America and had intended to get vaccinated there, but the Delta outbreak forced me to get one of the Chinese vaccines (SinoVac).

Unlike in America, where one could simply walk into any drug store and receive a vaccine of their choice, in China an appointment had to be made and it had to be verified that there was sufficient supply of the chosen vaccine at that location. Within minutes of being vaccinated, my WeChat account was updated to show that I had indeed received the jab.

All I needed to do was show the display whenever proof was required. It was highly efficient. A real shame for the Chinese population, as well as that of most of the world which depended on the Chinese vaccines, that they lacked efficacy. Today, the entire Chinese population is, in essence, unvaccinated since it has been too long since they were inoculated and now whatever effectiveness the vaccines had has expired.

That is a big part of the reason why the Chinese government was clinging to its zero-Covid policy. Another reason is that it has only 7 million hospital beds for 1.4 billion people. Not being able to get a Western vaccine became a problem when it came time to return to America for a visit, as Sinovac is not recognized as an accepted vaccine.

The reverse is also true—China recognizes only SinoVac or SinoPharm, so returning without an acknowledgement of having been vaccinated in China could create additional complications. Quarantines only became more draconian in China as the Omicron variant of Covid-19 emerged and became widespread in China. What had been a standard three-week protocol turned into 4, 5 and 6-week solitary confinement incarcerations.

As time went on, more and more foreigners and Chinese became fed up with the government’s zero-Covid policy. Foreigners left China in droves during the pandemic, some of them having been separated from their families or partners literally for years in the process. On top of everything else—the inconvenience, indignities, stress, anxiety and high costs—the zero tolerance policy prompted hundreds of thousands of foreigners throughout China to abandon the place.

Life was not a whole lot of fun with the constant protocols and procedures, security checks, forced mass testing and the inhuman way so many people were treated in the process. Travelling to and from America had become the theater of the absurd. If any flights were even available (and from January through March 2022, they were not) a one-way airfare from San Francisco to Shanghai was a high as $7,000 (or 300,000 miles) one-way in Economy.

This was a mammoth cost for a family of four to go home to visit loved ones and for most, simply inconceivable. The poor state of bilateral relations between America and China only exacerbated the cost, as tit-for-tat flight cancellations persisted throughout the pandemic. I had six different sets of flights to and from America cancelled for a single planned trip. Getting tested and approved to return to China was truly burdensome, as well. The Chinese government approved only six points of embarkation to the mainland from America.

Each city had as few as two approved testing centres (where blood was drawn and PCR tests administered) for between $400 and $650 per round of testing. If for any reason the results were not properly delivered to the designated Chinese consulate or embassy in full and on time, no approval code was granted and the procedure has to be repeated. Many people had to endure this process twice or three times to get it right, all the while having to pay for extra lodging, rental cars and food while they waited days (or up to a week) for the next flight.

I spent up to $3,000 each time I went through this process. On top of the horrendous cost of flights, a trip home was a five-figure proposition. Each time I returned from America I was greeted by people in hazmat suits, forced to get re-tested before leaving the airport, again before leaving the hotel, again if I was flying to my home city, then again a week following my arrival, having monitored my temperature (in writing, of course) for my first week back. If I wanted to travel elsewhere in China after that, I had to get tested before I flew, within 48 hours of returning home and within 72 hours after having returned.

The protocols have become even more burdensome, with some having to spend two weeks in solitary confinement at a hotel (at their own cost) before being allowed to return to their homes. My Covid-19 management experience during my time living and working in China would surely have seemed like pure madness to anyone who hadn’t accepted the trade-off for being permitted to live and work there.

For us, and for foreigners and Chinese citizens throughout China, it was simply the new normal. I’m sure that when I look back at that experience I will think that I was either a real trooper or nuts to have willingly endured China’s zero-Covid policy. I had a choice. I could have left whenever I wanted. That is not the reality for the vast majority of China’s 1.4 billion citizens, for whom there is no escape.

Daniel Wagner worked for the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank from 2021-2024. In 2023 he was seconded by the Bank to be Adaptation Finance Lead at COP28. Now he is CEO of Country Risk Solutions. His new book is “The China Epiphany”.