This civil war threatens to go out of control and can spread to neighbouring South Sudan, Chad, Libya and even Egypt.

Sudan is no stranger to conflict. Since independence in 1956, it has seen a spate of ethnic violence, 15 military coups, two civil wars—one that killed over two million and saw the creation of South Sudan. Another in the Darfur region saw over half a million killed and over three million displaced with unimaginable atrocities on both sides. And just as the nation appeared to be making some sort of transition to democracy, a raging internal strife between two power-crazy strongmen threatens to plunge it into another cycle of war.

The seeds of the present conflict go back to the Darfur Civil War of 2011. Sudan was then ruled by President Omar al-Bashir, who enlisted the services of Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo—a warlord also known as Hemedti—to quell the Darfur uprising. Hemedti used his Rapid Support Forces (RSF) an Arab militia called janjaweed that conducted widespread murders, rapes and atrocities in a two-year campaign of terror that brought the area under control. In return, he was made a lieutenant general and given control of gold and copper mines, and lucrative businesses to finance his operations. His RSF was also formalised into a paramilitary force. This was a way of keeping the army and its ambitious chief, General Abdel Fattah-al Burhan, in check. The arrangement worked for a while, till April 21, when the two strongmen got together and ousted President Bashir, ending three decades of autocratic rule. Yet, the military coup was not well received and a people’s movement soon erupted for return to civilian rule. In the protests that followed, the RSF perpetuated the infamous Khartoum massacre, killing and raping demonstrators wantonly. Eventually a joint civil-military government, headed by a civilian Prime Minister was put in place, with a promise of elections to be held in June. And then, as so often in Sudan, Burhan and Dagalo got together and engineered another coup that upended the civil government and ended Sudan’s brief tryst with democracy.

But when two unscrupulous power-hungry men get together, they usually fall out. This is exactly what happened. Dagalo’s RSF, with around 70-80,000 fighters is much smaller than the Sudan Armed Forces with around 200,000 personnel, but is far better armed, equipped and trained. The RSF was to be integrated in to the Sudan Armed Forces, an act which would make it directly under the army, and put Dagalo as subordinate to the army chief. He was loath to give up his power and the empire of mines and lucrative businesses that he had built up. Calls were also rising for probes into the numerous atrocities conducted by the RSF and the army. Dagalo resisted the move, demanding a greater power-sharing arrangement, and tensions rose to a point where Dagalo and Burhan were not even on talking terms with each other. The simmering tensions between the two finally erupted last month.

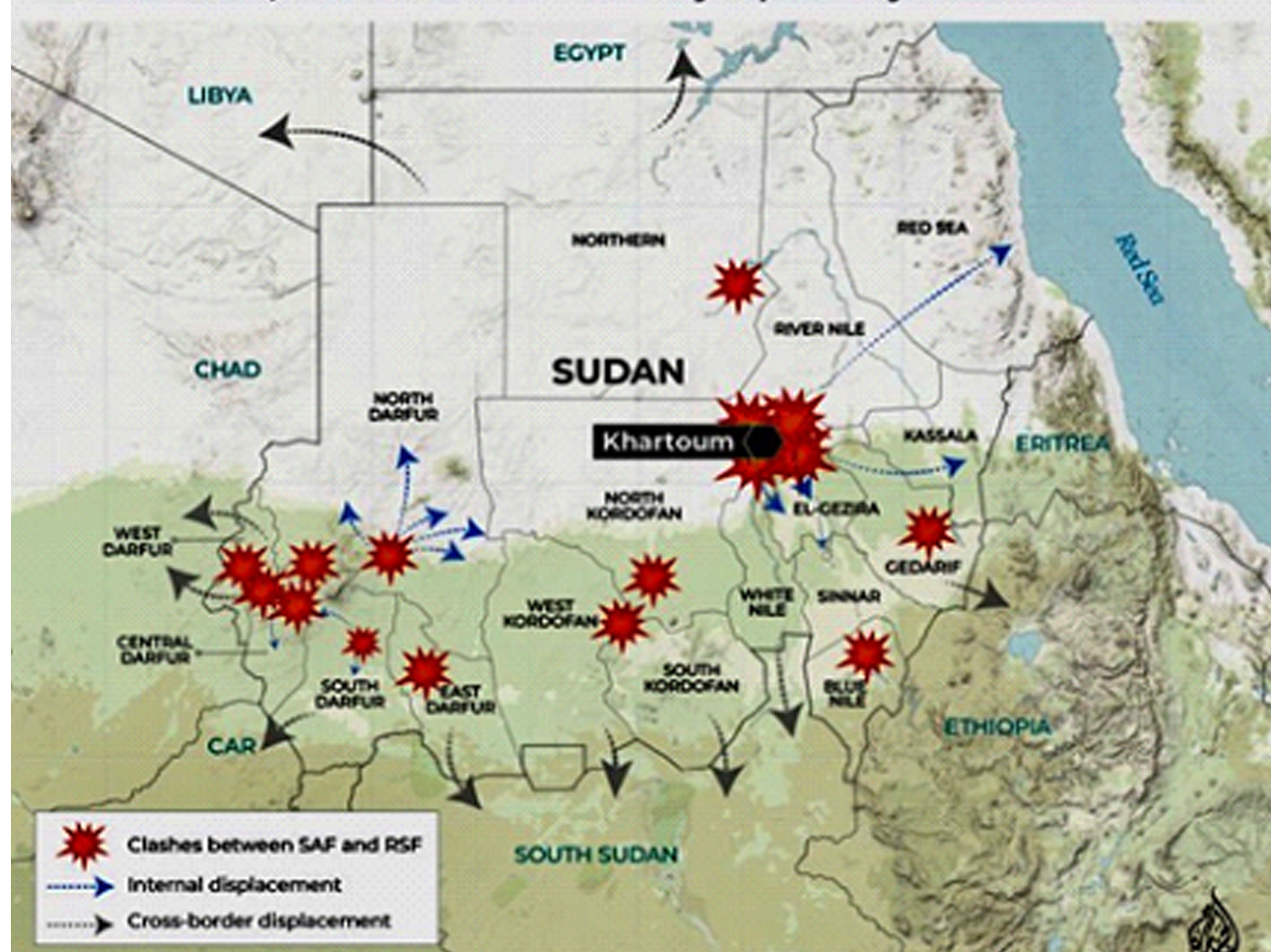

On 15 April, RSF fighters tried to take control of the Soha military base in Khartoum. They also launched multiple strikes across the country, including at Khartoum International Airport that damaged three airliners on ground. Other military bases, the Presidential Palace and key locations were also attacked and the violence spread all the way to Darfur. The army reacted violently, sending tanks into the streets of Khartoum, as jet fighters strafed targets beneath. In the fighting, as always, most of the victims were innocent civilians caught in the crossfire. And in the chaos, the looting and ransacking of property began. Sudan slipped into the familiar cycle of internal fighting, killings, rape, loot, internal displacement and the threat of a looming civil war.

Even as we go to print, the violence has claimed an estimated 600 lives, and started a stream of over 300,000 refugees. Three ceasefires have broken down, and the latest Eid ceasefire holds tenuously, which has given foreign nations time to evacuate their nationals. India’s Operation Kaveri successfully evacuated 4,000 Indians using aircraft that landed at Khartoum in virtual pitch darkness, and naval vessels that carried the remainder from Port Sudan. Coming in the wake of the successful evacuation of Indians from Ukraine, Yemen and other war zones, it is a measure of the clout we now possess to safeguard our diaspora. The US, UK, France, Germany and others have also followed suit. But once the foreigners leave, the opposing sides will be free to intensify their fight.

Pressure has built up from the international community, especially neighboring Egypt and Libya, for some kind of negotiations, with both sides refusing. Ironically, in this power-struggle, Burhan calls himself the “saviour of democracy”, while Hemedti paints himself as the bulwark against Islamists. Neither is true. Both are self-serving men fighting for control of Sudan and its vast resources.

But this civil war—like the ones that preceded it—threatens to go out of control and can spread to neighbouring South Sudan, Chad, Libya and even Egypt. Sudan is the third largest nation in Africa with a population of over 45 million, and the fighting can cause an immense humanitarian disaster. Starvation and disease, and the other scourges that come with conflict, could soon appear. As it is, there are fears of a bio hazard when one of the biological laboratories holding stocks of cholera pathogens was seized by rebels during the fighting, The conflict could also take on ethnic and tribal lines, and the resultant rift can spread across the country. It will also draw Islamic fundamentalists groups like Al Qaeda, Al Shabab, Boko Haram and others into the fray. They will join the hotchpotch of groups fighting there, and then use the resultant turmoil to spread their own fundamentalist ideology. It could lead to a long-protracted war, on the lines of Syria and Yemen and add to the arc of instability that now extends from African Sahel, Libya, Yemen, Syria and beyond.

One can only hope that groups like the African Union manage to get both sides to the negotiating table for some kind of agreement. But the damage has been done. The fighting has now hit the main cities of Khartoum and Port Sudan, which were spared the carnage of the earlier civil wars. Sudan’s hopes of transiting to democracy, which sparked briefly, has been doused once again. Although Burhan pledges to hold elections and restore civilian rule, the current climate will not permit it—till the RCF is defanged at least. The conflict will also draw outside forces into the fray. Russia and China have interest in Sudan’s vast natural resources—especially its oil and gold. Sudan is also the world’s sole supplier of gum Arabic—a product from its acacia trees that is essential to the food industry. Sudan’s vital position in North Africa, astride the crossroads of the Sahel, the Horn of Africa and the Red Sea also offers huge strategic advantages. Beijing has investments of over $200 billion in the country and Russia plans to build a major naval base in Port Sudan. The RSF has ties with the Wagner Group as well as groups fighting in Syria, UAE and Yemen. They could well enter the fray to support its ally and draw it into a protracted war with the Army. All in all, it seems that Sudan is headed for another long spell of instability.

With the world’s eyes focused on Ukraine, we have lost sight of even deadlier conflicts raging elsewhere. Sudan has seen over half a million deaths in the past decade. The Yemen civil war has claimed over 400,000 lives; and the war in Ethiopia has resulted in a staggering 2.5 million deaths. In all this, one has not even mentioned Afghanistan, Central Africa, Syria and others—32 different conflicts raging across the world that have claimed an estimated 2 million lives in the past year alone. These internal wars seem to go on with extended timelines for years if not decades. And their deadly toll is often that of innocent civilians, who are exploited by both sides, displaced, and fall prey to starvation and disease that these wars bring in their wake. The civil war in Sudan, unfortunately, seems to be headed the same way.

Ajay Singh is the international award-winning author of six books and over 200 articles. He is a regular contributor to The Sunday Guardian.