Sarma’s political graph shows the rise of a self-made man who learnt his craft on the streets, not on the pedigreed lap of a dynast.

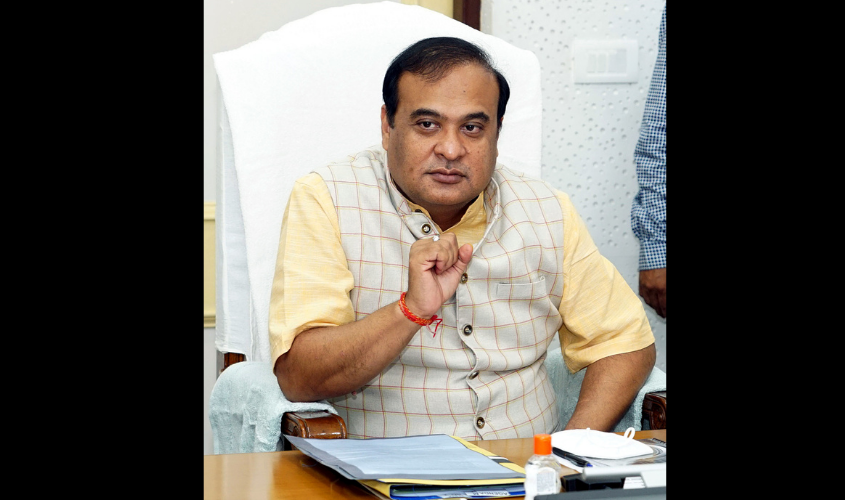

He is the insider turned outsider, turned insider again. That is the art of being Himanta Biswa Sarma. He may switch sides, but whichever camp he joins, he soon becomes one of the prime movers—never the outsider for long. HBS, as he is popularly known in a world where initials are a power accessory, was the Congress party’s rising star in Assam. For nearly a decade he was tipped to be the heir apparent to Tarun Gogoi, the septuagenarian Chief Minister. Then suddenly in August 2015, on the eve of a state election, the then third-term MLA quit the Congress and teamed up with the BJP. Sarma’s popularity with the masses remained intact despite the changeover, and he soon became now the BJP’s most potent weapon in the Northeast. That he would one day become Chief Minister is something that HBS knew much before anyone else. That he was able to make this dream into a reality is itself a testimony to his political acumen, and makes for a very interesting tale.

Born on 1 February 1969, Sarma joined the Congress in 1993 when Hiteswar Saikia was the Assam CM. But it was during Tarun Gogoi’s tenure that he emerged as the party’s GenNext face in Assam. Everyone assumed that after Gogoi, it would be Sarma who would be projected by the Congress as its next CM candidate—and indeed Sarma thought it as well. He was Gogoi’s Number 2, the de-facto Chief Minister, who dealt directly on his behalf with the other ministers in the Cabinet, and also with the party cadres. This worked well till 2011 until Tarun Gogoi’s 29-year-old son Gaurav—an engineer-cum-development worker—joined politics. Senior Gogoi asked his deputy Sarma to take Gaurav under his wings and train him. Himanta obliged but he soon got the feeling that young Gogoi’s aim went beyond being an apprentice to Sarma. They were both after the same job.

Then came the 2014 Lok Sabha elections that saw the BJP sweep the country. The Narendra Modi effect was felt in Assam too, where the Congress was reduced to a mere three MPs and the BJP won seven of the total 15 seats. This was a sign that the three-term Chief Minister, Tarun Gogoi, was losing his grip on the state, more so when the Congress was defeated in the municipal elections that followed soon after the general elections. Himanta genuinely believed that given this situation, especially with the BJP making inroads in the Northeast, the party leadership would agree to a regime change in his favour.

An emergency meeting was called at the then Congress vice president Rahul Gandhi’s house in New Delhi sometime in August 2015. In attendance were Himanta, Tarun Gogoi and the party general-secretary in charge of Assam, C.P. Joshi. The way Himanta tells it, this meeting was the last push he needed to quit the Congress. He recalls that he was totally disillusioned with the way Rahul handled the meeting. As he said later, “Rahul was distracted and more interested in playing with his pet dog, instead of neutralizing the issue.” According to Sarma, Rahul did not refer to the main issue at hand, which was his plea for a change of CM. Instead, when Sarma pointed out that it was he who had done the grunt work for the 2011 Congress win in Assam, down to choosing the candidates and the bulk of the campaign rallies, Rahul shrugged and said—so what?

But Himanta had his work cut out in the BJP as well. Since he was a newcomer, he was not immediately made the CM face, but instead was handed back his old job from the Congress days, that of being No. 2. This earned him a lot of barbs from his former colleagues, who wondered why he had quit in the first place. But HBS put his head down, established a direct line of communication with the all-powerful Amit Shan and focused on the deliverables. Under his stewardship the BJP spread its roots in the Northeast and Sarma was made Convenor of the Northeast Democratic Alliance (NEDA), a platform where all the CMs of the NDA-ruled states reported to Sarma. This was only fitting, for all the BJP’s wins in the Northeast had been crafted by Sarma.

As he told me once when I interviewed him for my book, The Contenders, “I was the Number 2 in Tarun Gogoi’s cabinet but I was never acknowledged as such. Whenever there was a crisis they turned to me to deliver. But when there was an official function I was never called to the dais. I was never considered the Official Number 2. With the BJP, this is not the case. In the BJP I feel respected.”

Sarma’s political graph shows the rise of a self-made man who learnt his craft on the streets, not on the pedigreed lap of a dynast. He joined the All India Assam Students Union (AASU) in the sixth standard. That was the time of the Assam agitation against illegal immigrants spearheaded by the then CM and Asom Gana Parishad leader, Prafulla Kumar Mahanta. Sometime during 1979–1980, HBS came in touch with Mahanta and his deputy, Bhrigu Phukan. A few years later, around 1987, he even flirted with the United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA), running the odd errand for the separatist outfit. An interesting side story is that he won his first election in 2001 on a Congress ticket by defeating the then AGP leader, Bhrigu Kumar Phukan from Jalukbari. After graduating from Guwahati’s prestigious Cotton College, where he was a two-term general secretary from the AASU, Sarma went on to study law at the Government Law College and even holds a PhD in political science. Having tasted agitational politics at such a young age, he was quick to realise that for him the lure was not the courtroom but the court of the people. In the early 1990s, when the government had begun its crackdown on the ULFA leaders, Sarma came in contact with the then Congress CM, Hiteswar Saikia, who was impressed with the young firebrand.

The BJP may have made Sonowal the Assam CM in 2016, but the cut and thrust of the government was in Sarma’s hands. He held the key portfolios of finance, education, planning and development, health and family welfare in the Assam government. During Covid-19, it was Sarma who became the face of government outreach. He has since got flak for declaring Assam safe enough for people to venture mask-less on the eve of the popular Bihu festival, but being Sarma, his political capital saw him through this gaffe straight to the CM’s chair.

The BJP waited over a week after the Assam results before naming Sarma as the CM designate. The party already had a sitting CM in place. However, Sarma had Amit Shah’s complete backing. He had also gone out of his way to please those who matter in the RSS. Sarma’s strong defence of the CAA, GST also found favour with the Prime Minister. Once when I asked him if he was peddling Hindutva under duress or by conviction, Sarma countered by asking, “How can you differentiate Assamese identity from Hindu identity? First, we are Hindu, which has both an element of Sanatan Dharma and Sufism. Second, we are Assamese, for we also have our inherent tribal culture. But the kind of Islamic thought that has been brought to Assam by Bangladeshi migrants is not Sufism and cannot be part of our identity.”

The only roadblock that stood between him and the CM’s chair was the fact that there was no dire reason to remove Sonowal either. But Sarma made it clear that he was not going to play No. 2 again. Perhaps if the BJP leadership was not facing so much criticism of its mishandling of the Covid crisis, or its failure to live up to its hype and wrest West Bengal from Mamata Banerjee, Sarma may not have been able to push his candidature through. Then again, there is also a question as to how he would have reacted to having been marginalized. He made it clear that a Cabinet ministership at the Centre was not the consolation prize he craved. In fact, he was done with consolation prizes. It was time he was given his due.

Sarma has always believed in Karma—ever since his childhood when he helped his father translate Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s Geeta Rahasya into Assamese. “You can only do your work, the result depends on someone above you,” he told me once. Well, it seems as if someone above him was finally listening.