The book, Azaad by Ghulam Nabi Azad gives a ringside view of the Congress during the last five decades.

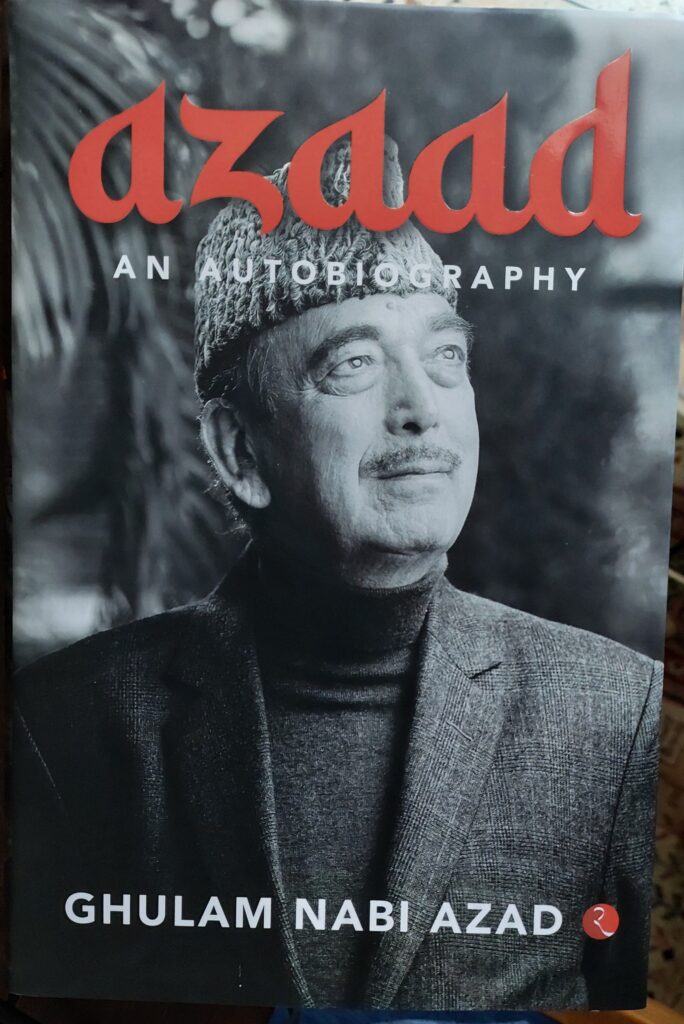

NEW DELHI: Ghulam Nabi Azad’s autobiography hit the stands last week, and got its fair share of media headlines. What makes the book (titled Azaad) interesting is not so much the sensational bits about his critique of the current state of the Congress, but instead it is his account of the five decades that he spent in the party. Apart from Mohsina Kidwai, Azad is one of the few (former) Congress leaders who can trace his lineage to Indira Gandhi’s Council of ministers. Having spent five decades in the Congress he has worked closely with six Congress presidents—Indira, Rajiv Gandhi, Narasimha Rao, Sitaram Kesri, Sonia Gandhi and Rahul.

In fact the title of the book is misleading. It works in the limited sense in that it’s a clever play on Azad’s own name and the fact that he is free from bowing to a leadership he has now outgrown. But having said that, it is also short-selling a book which gives us a ringside view of the Congress during the last five decades. The book is full of anecdotes and interactions with the Congress leadership down the years. As Youth Congress president, and a close friend of Sanjay Gandhi, Azad got to interact with Indira Gandhi quite closely. He narrates how she let him run the IYC without much interference, down to letting him nominate his own team. On one occasion when she made two recommendations for the post of general secretary, Azad had to turn them down as they didn’t fit the criteria. Instead of being upbraided for this, the then Congress president told him that she wasn’t aware of the criteria when she forwarded the names, and added, “I cannot always be right.”

There is also an amusing anecdote about how Azad was offered the Law, Justice and Company Affairs portfolio in Indira’s Council of Ministers. Though he has a law degree, it was by correspondence and one he had learned by rote but that’s about it. When he expressed dismay Indira told him that R.K. Dhawan had looked up the Who’s Who (book of MPs) where Azad had listed his degree. Azad says that the first thing he did when he got elected a second time was to delete the law degree and instead write down his degree in zoology, “to make sure I don’t fall into the same law trap again.” Well, that degree got him the post of Parliamentary Affairs Minister, so clearly someone in the PMO had a sense of humour back then.

Azad also talks about his closeness and differences with both Sitaram Kesri and Narasimha Rao. It is telling that the duo is spared the bitterness that creeps into the narrative when he talks about his fallout with the current Congress leadership. In fact, having played a key role in orchestrating the ouster of both these gentlemen from the post of Congress president, Azad expresses regret over his harsh actions back then.

Post the Babri demolition, when Parliament was disrupted with cries for Rao’s resignation, as the Parliamentary Affairs Minister it fell to Azad to look for a way out. The way out that Azad suggested to Rao was that instead of the PM resigning, the then Home Minister S.B. Chavan should take the fall. Rao told Azad to convey this decision to Chavan. Azad then says that Chavan agreed to meet Rao the next day and offer his resignation. But when the appointed hour came, Chavan did not show up. He went missing for the next few days by which time the Opposition lost its steam and stopped pressing for his resignation. “I realised that Rao had played a crafty trick on me…he must have advised him to go underground and resurface after the storm is over,” writes Azad, recalling that both Rao and Chavan were friends since their student days. “Clearly the PM was buying time as he had no desire to axe Chavan” is the belated realisation.

Azad also narrates how he and the late Madhavrao Scindia tried to get Rao (who was also the Congress president) to appoint a working president and PCC office bearers. They were asked by Rao to key in the list of contenders in a computer at Rao’s residence. Rao was a technology buff like Rajiv, but as Azad points out, Rajiv used to type with one finger while “all ten of Rao’s fingers danced on the keyboard like butterflies”. However, organisational work did not inspire the said dance, for six months passed without Rao taking any action. Finally when asked, Rao claimed that the list had got wiped out so could the duo key it in again. Azad certainly has an eye for detail and a gift for story telling for it is these little nuggets that make the narration all the more enjoyable.

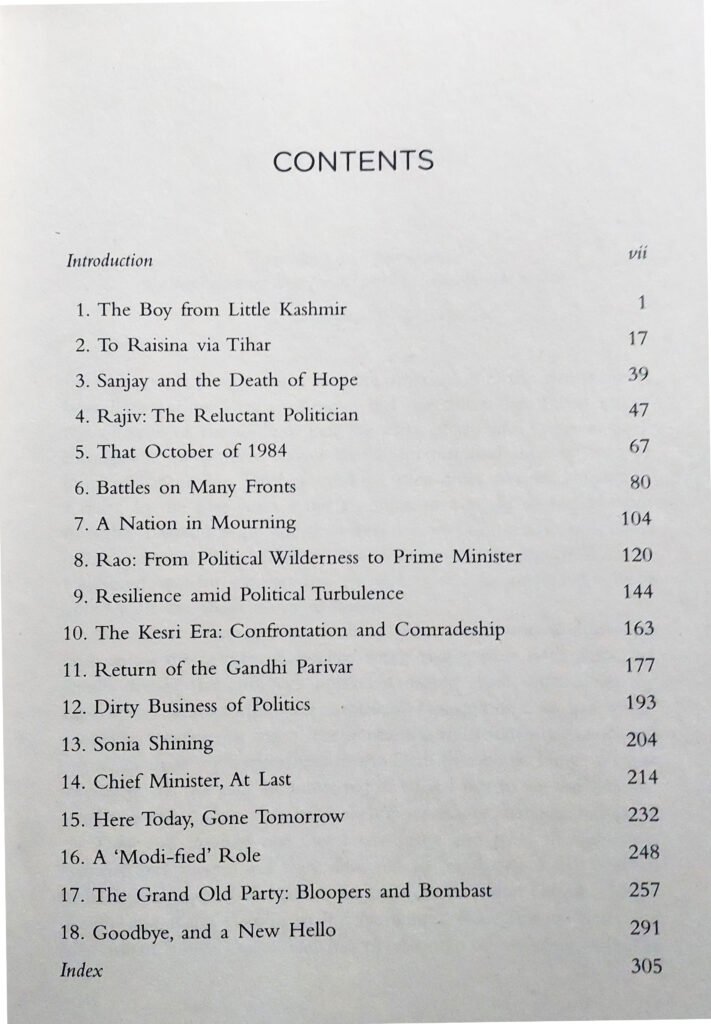

As far as the big picture is concerned, it is in the postscript in a chapter with a very melodramatic title: “The Grand Old Party: Bloopers & Bombast”. It is here that the indulgent tone of the narrative takes a sharp edge. Taking up from where the G23 letter left off, Azad talks about all that is wrong with the Congress. And having handled almost every state in India as general secretary, his observations make for a very telling critique. (Statutory warning: like all first-hand accounts this one too is not without the author’s biases). Before he goes in for a state by state analysis, Azad issues an alert: That those Congress leaders who compare the current loss to Indira Gandhi’s defeat in 1977 and expecting a similar comeback, are making a big mistake, for three reasons. One, being that despite the electoral loss both Indira and Sanjay continued to reach out to the people. Two, both were accessible to the party workers and leaders. Three, the Congress organisation was present in every state and district. Since then this space has been ceded to regional parties like the SP, BSP, NCP, RJD, TRS, BJD, TMC, YSRCP, AAP and Shiv Sena. “Except in Tamil Nadu where the Congress had to face two regional parties, the DMK and AIADMK, today the Congress has more competition from regional parties than national parties,” concludes Azad adding that “Hence the present situation cannot be compared with the 1977-79 scenario”.

While talking about how Congress lost almost every state, Azad adds another nugget to the Himanta Biswa Sarma (HBS) story. He claims that the reason Sarma rebelled was that in 2001 the then Assam Chief Minister, Tarun Gogoi had promised HBS that he would make him the CM. But when the Congress won in 2006 and later in 2011, Gogoi remained the CM. An upset HBS reached out to Sonia who asked Azad to look into the matter. Azad asked for a show of strength, and Himanta showed up with 45 MLAs while Gogoi sent only 7. Azad then writes that when he conveyed this to Sonia she said that Himanta should become CM. Before Azad could leave for Assam, Rahul intervened on Gogoi’s behalf and said if Himanta wanted to leave the party, then “let him go”. The fact that Sonia had initially wanted to replace Gogoi with Himanta is not known to many, but it is a fact that I have since checked with the current Assam Chief Minister.

While Azad has been criticised for not speaking up earlier (like when Rahul tore up the controversial ordinance passed by Manmohan Singh’s government

The book is an engaging chronicle of the Congress rise and fall, and a must read for any student of politics. Azad is right when he complained that there was more to the book than the Rahul bits. “Why is the media only focusing on the Rahul chapter? It is not his (Rahul’s) autobiography, that’s only one chapter,” he told NewsX. For me personally the Indira and Sanjay years make the best read, and indeed Azad dwells the most on them and his time in the Youth Congress, for that is when he was just starting out and nothing could be headier than the sweat of agitational politics, the enviable access to the party’s top leadership despite being a junior, and the first cut of realpolitik.