Every new case of TB infection is a grim reminder of what we could have averted if infection control measures were more effective, including treating latent TB infection.

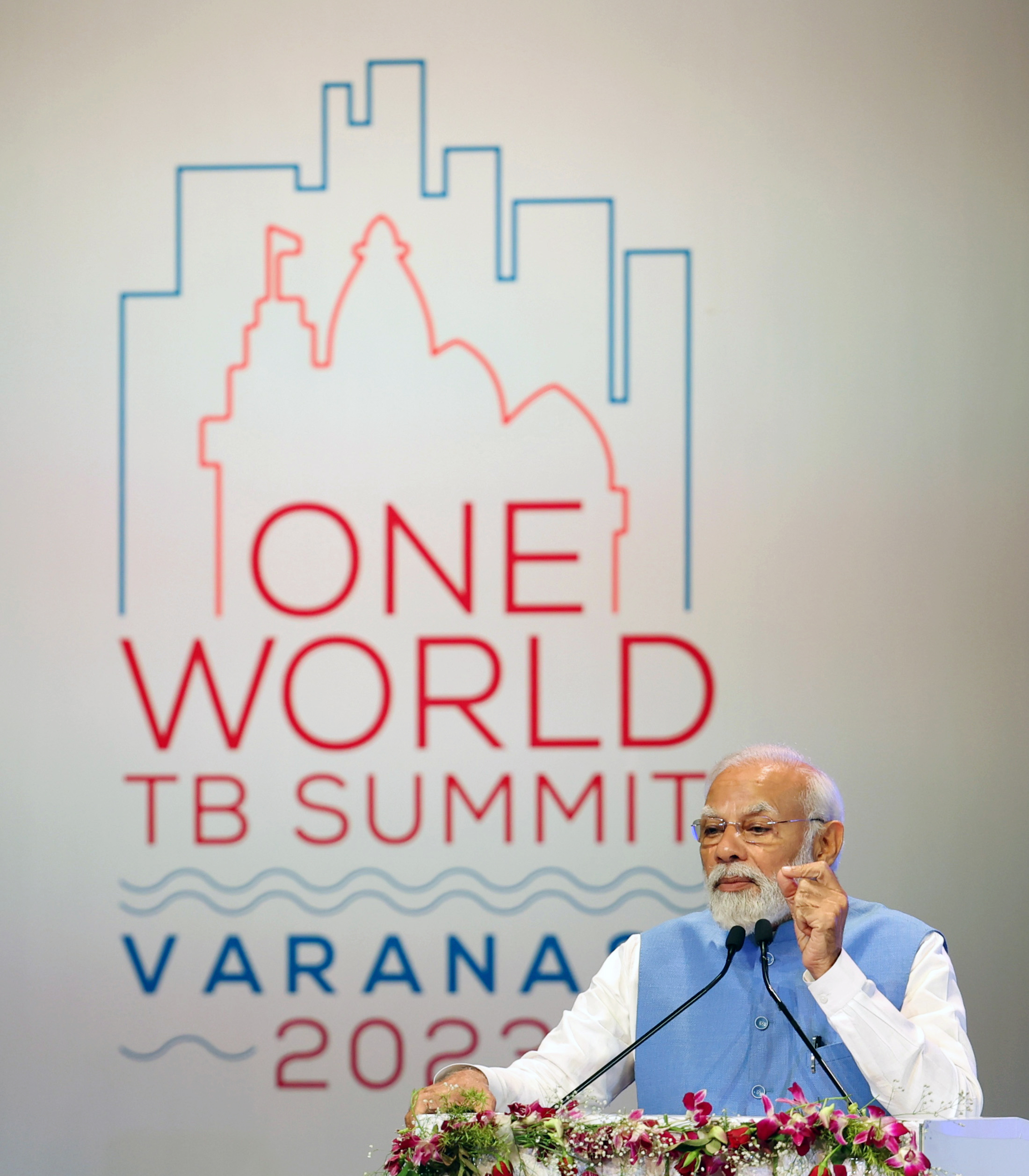

As per the latest Global TB Report of the World Health Organization, TB rates in India have declined by one-fifth between 2015 and 2021. TB deaths have also reduced by around 7% in the country during this period. The Global TB Summit in Varanasi to mark this year’s World TB Day (24th March) is part of India’s Presidency year of G-20.

The Indian Prime Minister had set a target to end TB by 2025—five years ahead of the global goal to end TB as a public health threat by 2030. “India’s ambitious mission to eliminate TB five years before the global target is commendable. About 10-15 years back, there were only a few national reference laboratories to test for drug-resistant TB. Now, the country has such diagnostics in every district which is a major leap forward. Indian pharmaceutical companies have also made a stellar contribution in supplying life-saving TB medicines within the nation and globally at an affordable cost. This is more significant as TB medicine prices are governed under The Drugs Prices Control Order (DPCO), under Essential Commodities Act. Recently, an Indian company has slashed prices of molecular TB diagnostics which is a welcome step. The number of people with drug-resistant TB who get diagnosed and treated has also risen proportionately over the past decade.

India’s leadership in TB research is also exemplary, with several late-stage clinical studies in the final stages—including those on possible TB vaccines—the results of which may come out soon later this month at the government-run National Institute for Research in Tuberculosis, Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR).

With the domestic capacity to produce and supply the best TB medicines and diagnostics, and robust TB R&D, India has demonstrated leadership in scaling up access to TB prevention, diagnostics, treatment, and care as no other country globally. Despite these important successes, we need much stronger actions with a sense of urgency and purpose if we are to end TB by 2025 in India.

TB rates need to decline many times more steeply than the current rate of annual TB decline. Likewise, TB deaths too need to be reduced quickly. We need to remember that TB is a preventable and curable disease, and even one death is a death too many. Every new case of TB infection is a grim reminder of what we could have averted if infection control measures were more effective—including treating latent TB infection.

Several recent initiatives of the National TB Elimination Programme of the government of India have begun to yield fruit. For example, the Public Private Partnership (PPP) model of the government-run programme is very effective and needs to be emulated by other programmes such as the National AIDS Control Programme (NACP). For instance, in South Mumbai, Unison Medicare and Research Centre is the only private sector entity recognized by the government-run programme, and patients can access the latest medicines like Bedaquiline here (supplied by the government within hours of due requisition). But more private sector healthcare services need to be approved so that they can effectively contribute towards TB elimination. Unfortunately, stigma against TB and, more so, against MDR-TB is much more among doctors.

TB DEADLIEST INFECTIOUS DISEASE IN INDIA

TB is the world’s deadliest infectious disease, with over half a million deaths attributed to it in 2021 alone. COVID-19, which has emerged as the deadliest infectious disease globally, caused half a million deaths in the country over a period of three years. In 2021, India had an estimated 3 million (30 lakhs) new TB cases, out of which 54,000 were among people living with HIV. 38% of TB deaths globally took place in India, with half a million people dying of TB in the country—out of which 11,000 were people living with HIV. TB is the most common opportunistic infection and the biggest cause of death among people living with HIV. This is unacceptable because we can prevent, diagnose, and treat TB—even among people living with HIV.

We also need to focus more on children and young people, as almost one out of every ten persons in India who got TB was under the age of 14. Also, in India, one in five people who was estimated to have active TB disease in 2021 was over 55 years of age (over 619,000 people). One-third of these older persons could not get access to TB services (or were not notified to the government-run National TB Elimination Programme).

With optimal infection control practices in homes, communities, and healthcare facilities, we can break the chain of infection transmission of not only TB but also its drug-resistant strains. In addition, it is important for India to ensure that every person with TB is being treated with a combination regimen of medicines that he or she is sensitive to (medicines that work on the person). TB drug resistance is making medicines ineffective, and the choices left are limited with poorer treatment outcomes.

In 2021, India had 119,000 new cases of multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB), out of which less than half were put on treatment. This has to change rapidly so that every person with drug-resistant strains has access to a regimen with medicines that work on the person.

Latest TB research results have shown that all-oral treatment of drug-resistant TB can be much shorter, safer, and more effective than the older standard of care regimen (of around 2 years with injectables). The new research shows the safety and efficacy of several new medicines such as Bedaquiline, Pretomanid, or Delamanid. Regimens such as BPaL (Bedaquline, Pretomanid, and Linezolid) or BPaLM (M stands for Moxifloxacin) have proven effective, and toxicity related to Linezolid was much reduced with reduced dosage and duration of the drug in the regimen—without impacting high treatment success rates of these regimens. Though BPaL is routinely used in South Africa and other African countries, in India, it is still under pilot-mode.

TB MOLECULAR TESTS REDUCE TURNAROUND TIME

Almost one-third of the people estimated to have TB disease in 2021 were left out of TB services. We need to ensure that the latest diagnostic tools, such as the TB LAM (Lipoarabinomannan) urine test, are accessible to everyone who needs them. TB molecular tests, such as the Gene Xpert and the indigenously made True Nat, are available in every district of India. These tests confirm active TB disease as well as resistance to Rifampicin medicine (which is also a surrogate marker for resistance to Isoniazid). These molecular tests reduce the turnaround time for detection from 1.5 months to 1.5 hours. Despite the strong evidence of public health benefits of using these tests upfront when a person with presumptive TB walks in for screening, we are not walking the talk on it by using them upfront everywhere. The best diagnostic tests should be free and easily accessible to those who need them everywhere, to detect TB disease as well as drug resistance, so that effective treatment can begin without delay.

Science has shown that every case of new active TB disease comes from the pool of people with latent TB infection. If we treat people with latent TB with effective medicines so that they never transition to active disease, we can give a major thrust to efforts to end TB with rapidly declining new cases. This is especially important for those who are more at risk of progressing to active TB disease from latent TB, such as people with HIV, those who have diabetes, or those who use tobacco, are immune-compromised, among others.

We have the latest therapies to treat latent TB infection so that the risk of progression to active TB disease is decimated. However, the latest shorter regimens of Rifapentin and Isoniazid made by Indian pharmaceuticals, such as McLeods, for the rest of the world are not available within the nation. Only a few pharmaceutical companies, such as McLeods, Lupin, and Zydus Cadila, make the majority of TB drugs. But with diminishing incentives and rising challenges, the government needs to pay attention to ensure that TB drug research and development and manufacturing continue to remain robust for the nation as well as the world. In fifty years

Dr Ishwar Gilada is consultant in HIV and Infectious Diseases; Secretary General of People’s Health Organization; President Emeritus of AIDS Society of India and Governing Council Member of International AIDS Society, gilada@usa.net; www.unisonmedicare.com

Dr Prapti Gilada is Clinical Microbiologist with special interest in TB Research at Masina Hospital and Unison Medicare &; Research Centre, Mumbai, praptigilada@gmail.com