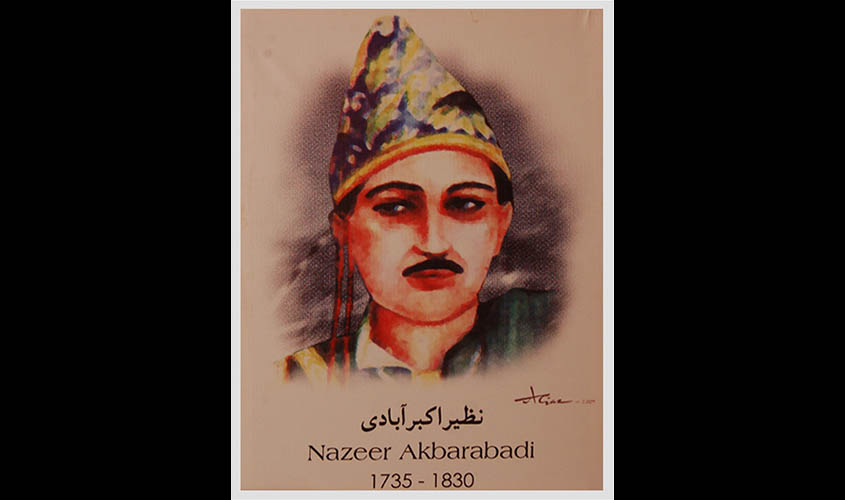

There have been times and moments in our history when men of letters have marked their excellence through extraordinary ways of doing things such as production of fascinating Urdu poetry celebrating Hindu festivals of Dussehra, Diwali, Basant and Holi in a language that captured the best of the festive emotions. Urdu poet Nazir Akbarabadi (1735-1830), who was born and grew up in Delhi, but flourished in Agra-Mathura region, was one such multifaceted personality who rose above narrow religious and sectarian boundaries to compose a large number of works in different genres of poetry. His voluminous Kulliyaat or Collected Works, published among others by the classic Nawal Kishore press of Lucknow, offers significant light on the celebration of little pleasures of life—fairs, festivals, fresh burst of energy with the season changing for the better, natural bounties such as juicy summer fruits, some little love as well as chance or opportunity to interact with women in a regressive society, besides other possibilities.

Nazir Akbarabadi wrote at registers ranging from popular or subaltern level to high poetry of love

The poems on Diwali reveal not only markets buzzing in preparation, with earthen lamps illuminated everywhere, but also some people going for the broke in the widespread practice of gambling on the occasion. For the pious and the innocent, the poet would announce that the lamps were lighted in all the houses and sweetshops were attracting customers:

Har ek makan mein jala phir diya Diwali ka

Har ek taraf ko ujala hua Diwali ka

Mithaiyon ki dukanen laga ke halwai

Pukarte hain ke lala Diwali hai aayi.

On the other hand, the sinner is hell-bent on losing not only his house, but also his wife in Diwali-eve gambling with all of her jewellery almost gone. The woman is abused as a loose character and threatened:

Woh uske jhonte pakad kar kahe hay marunga

Tera jo gahna hai sab taar taar utarunga

Haweli apni tow ek dao par mayen harunga

Yeh sab tow hara hun khandi tujhe bhi harunga

The poet also reminds the devout that though Dussehra is celebrated with much gaiety, but Diwali is a much more auspicious festival:

Hai Dussehre mein bhi yun go farhat-o zinat nazir

Par Diwali bhi ajab pakizatar tehwaar hai

The endless possibility of dangerous fun is especially narrated by the poet in several compositions on Holi, when the participants are physically charged for amorous advances, taking advantage of the refrain later pronounced in Hindi, bura na mano Holi hai! Here is a polite sample of musical instruments used to announce the arrival of Holi playing groups and friends and lovers gleefully showering each other with colourful gestures:

Mridange baajen taal baje kuchh khanak khanak kuchh dhanak dhanak

Jab khubaan aaye rang bhare phir kya kya Holi jhamak uthi

Kuchh husn ki jhamken naaz bharen kuchh shokhi naaz adaaon ki

Sab chaahne wale gird khade nazara karte hansi khushi

Mahbub bhigoyen aashiq ko aur aashiq hanskar unko bhi

And, some compositions are truly meant to fit straight into classical Hindustani music capturing the pleasant mood of the festive season:

Jab phagun rang jhamakte hon tab dekh baharen Holi ki

Aur daf ke shor khadkate hon tab dekh baharen Holi ki

Much of it was possible also because Nazir Akbarabadi grew up in Delhi at a time of cultural efflorescence actively promoted by later Mughal emperors, especially Muhammad Shah (1719-1748), nick-named Rangila, the colourful, even as political power and authority was being continuously shaken by Afghan invaders from the North-West. Within the circle of eminent Urdu poets, Nazir’s life and career overlapped between two stalwarts—Mir Taqi Mir (1722-1810) and Mirza Ghalib (1797-1869)—with fruitful interactions. Together they excelled in their literary practice, which was central to their lives, in their own distinct ways. Nazir is often not counted in the history of classical Urdu literature because of the way he catered to the popular tastes in compositions of the kind given above as samples. His celebration of Hindu religious practices, traditions, myths and legends need serious consideration especially in times when Hindi/Urdu and Hindu/Muslim divide and conflict serve as fodder for those who thrive on religious communalism.