The two Banerjees illustrate how water of the Bhagirathi has been flowing through a land proud of its past, uncertain of its present and blindfolded of its future.

This is a story of two Banerjees from Bengal, one who helped set up the Indian National Congress, the other enticing fringe elements of a crumbling Congress to expedite its dismantle; one who was a towering national leader reverentially called “Rashtraguru”, the other is a successful politician who knows how to create an election winning force in a system of loopholes; one who is forgotten today, the other keen to create enduring legacy like Ozymandias with help from courtiers. The two Banerjees illustrate how water of the Bhagirathi has been flowing through a land proud of its past, uncertain of its present and blindfolded of its future.

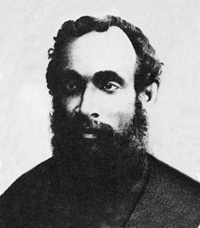

The tremendous influence of Surendranath Banerjee across India in the formative days of India’s nationalism was acknowledged by the people as well as the British civil servants including Allan Octavian Hume, the man who worked relentlessly for setting up the Indian National Congress. In 1877, after Surendranath toured India, Henry Cotton, a member of the Indian Civil Service observed that it was inconceivable that a Bengali would have so much influence across the nation, in Punjab for instance, from Dacca to Multan and a Bengali would build public opinion from Peshawar to Chittagong. But more glaring was when Allan Octavian Hume, after the lukewarm first session of Congress in 1885, approached Surendranath to ensure the success of its second session in 1886.

Surendranath, according to historian Ramesh Chandra Majumdar, brought in politics on the plate of a Bengalee. “The fact that the educated young Bengalees became more concerned with securing a voice in the country’s government than with social and religious reforms

Move over to the Banerjee of today and her politics of unifying the nation under her idea of India modelled in no small measure on the present day state of West Bengal. Mamata Banerjee, the third term Chief Minister of West Bengal, is now busy creating a rejuvenated alternative to the 140-year-old Congress, now owned by the two great grandchildren of Motilal Nehru, who was among the first few confidants of Gandhi acting effortlessly as a bridge between two towering leaders Chittaranjan Das and Gandhi. Mamata, too, had her grooming in politics from the old Congress party and interestingly surfaced exactly 100 years after the party was created. Now she seems to be keen on presiding over its final rites, as she sees it.

When in 1876 Indian Association or Bharat Sabha was set up at a meeting in the Albert Hall, the present Coffee House opposite to the Presidency College (now University), Surendranath was the star orator. The 28-year-old was deeply moved by the freedom struggles in Europe and particularly by Joseph Mazzini. His oratory deeply influenced the youth of Bengal. Some speeches of Banerjee in the 19th century were on the rise of the Sikhs and how Joseph Mazzini created the Young Italy movement. The Banerjee of the 21st century does not suffer from any hangover of knowledge, national or international. Nor is she a great orator, not even in her native tongue. Yet her incoherent speeches, often with hilarious gaffes, are attractive enough to many who support her. Many reasonably erudite personalities like Yashwant Sinha, Subramanian Swamy et al are flocking to her camp attracted either by her charm or seeking refuge away from their fear of going into oblivion.

How do the statures of the two Banerjees from Kolkata compare? The first one was a pioneer, pioneer of political nationalism. Surendranath brought in a pan India approach in his lectures with the intention of uniting Indians of all religions, speaking different languages and living across the country under a common national cause. In fact after the first meeting of the Indian Association, pan Indian opinion building was one of the major objectives of Surendranath. And for that he knew he had to build a bridge between all communities, particularly between the Hindus and the Muslims. Clearly, this was a deviation from the “anti-Muslim ruler” type nationalism that had been the story of Anandamath. Historian S. Irfan Habib acknowledges Surendranath as a proponent of early liberal nationalism. “In one of his many speeches and writings he (Surendranath) denies that there is any antagonism whatsoever between the two great races who inhabit this vast continent and who together form the Indian nation. He goes back to history, particularly the past eight hundred years, to establish through some interesting instances that we have a shared past of goodwill and amity,” writes Habib. Mamata, less articulate and arguably much less erudite, perhaps wants to mould herself in this fashion, a separate pan India challenger of sorts of Narendra Modi, the Indian Prime Minister.

In the tale of two Banerjees the obvious question is a relative analysis of their success. The pioneer Banerjee, despite his sacrifice and unquestioned nationalism, went into sunset, finally after an electoral defeat by a young doctor, Bidhan Chandra Ray. The current one, still trying her hand in emerging in the national scene, had a small blemish of an electoral loss but that proved irrelevant. Since she never had any towering presence in the nation’s life (at least so far) she need not go into sunset like Surendranath. History does not have any reason to recall her with a positive warmth save those for historians who rejoice at the loss of the Left citadel in West Bengal. For the current Banerjee the firm imprint in the national political history could be dethroning the current BJP narrative, structured in no small way on Bankim’s Anandamath and establishing one that was dreamt by Surendranath, “one of our earliest liberal nationalists”. But the 21st century’s aspirational Banerjee is yet to grasp the nuance between appeasement politics and nationalism based on growth and prosperity for all. For instance, she is far removed yet from the pioneer Banerjee’s address in Dacca, “Hindus and Mohamedans! We are brothers; and as brothers sometimes quarrel, so too they always make up their quarrels in the presence of the larger interests of the family. I ask you, Hindus and Mohamedans to forget your jealousies and your petty differences in the name of your common country and for the promotion of her dearest interests.”

Times are different. Much water has flown in the last 140 years. The change is captured by the personalities of the two Banerjees from Kolkata. The two contrasting personalities also capture the metamorphosis of Kolkata, the city that taught India nationalism.

Author Sugato Hazra’s latest book is “Losing the Plot: The Political Isolation of Bengal”.