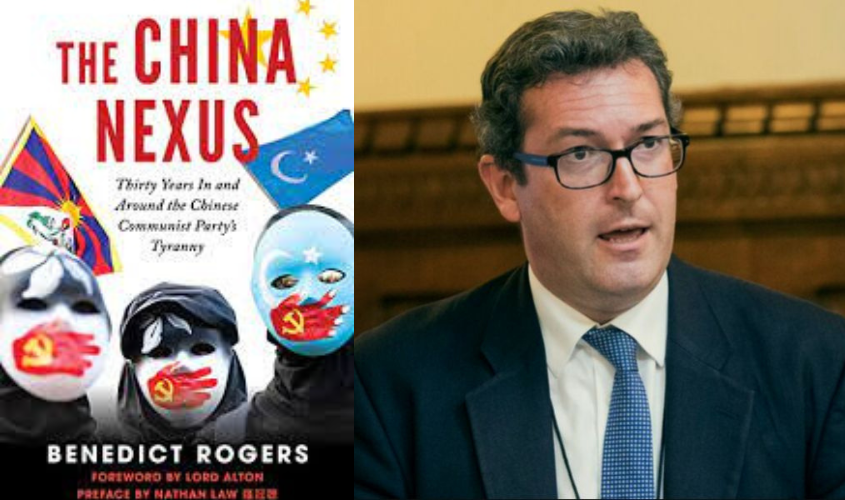

Following is an extract on Tibet from the book ‘China Nexus’ by British human rights activist and author Benedict Rogers, made exclusively available to The Sunday Guardian in India, ahead of his visit to New Delhi later in the week.

INTRODUCTION

China is at a crossroads. It is transitioning from destination of choice for foreign investment to growing threat to the international rules-based order. It is moving from an era of reform and opening to a new chapter of repression and aggression. It is morphing from potential economic partner to economic competitor, a security challenge and a direct threat to free and open societies around the world.

With Xi Jinping’s new axis of authoritarianism with Vladimir Putin, it is now at war with the democratic world—not yet militarily, but in terms of values and the battle for influence on the world stage. It’s a war of hearts and minds, attrition and coercion, and—on India’s border with China—a war in which shots are sometimes fired. In this war, India needs to pick a side, and India’s interests are clearly not with Xi Jinping.

This new book, The China Nexus, covers the entire landscape of China’s human rights crisis—from the genocide of the Uyghurs to the atrocities in Tibet, from the persecution of Christians and Falun Gong and forced organ harvesting to the crackdown on civil society, lawyers, bloggers, media and dissent, from the dismantling of Hong Kong’s freedoms in breach of an international treaty to the threats to Taiwan, as well as China’s relations with Myanmar and North Korea. Among these themes the book weaves together the author’s personal experiences travelling in and around China over the past 30 years, beginning with his experiences teaching English in Qingdao aged 18.

The book ends with a practical set of policy recommendations for the international community and includes analysis from Indian academics. The Foreword is by Lord Alton and the Preface by Nathan Law, and it has been endorsed by the last Governor of Hong Kong Chris Patten, former Foreign Secretary Sir Malcolm Rifkind, Chinese dissident Ai Weiwei and other public figures around the world.

BOOK EXTRACT

In the Ristorante Camponeschi, in Rome’s Piazza Farnese—a restaurant which claims to have been frequented by world leaders such as Al Gore, Shimon Peres, and Mikhail Gorbachev, and Hollywood stars like Sylvester Stallone and Liza Minnelli—I sat next to the “Sikyong”—or prime minister—of the Central Tibetan Administration, Tibet’s government-in-exile. It was November 2021…

Penpa Tsering was elected to his five-year term as Tibet’s secular political leader in May 2021, replacing the first Sikyong, Lobsang Sangay, whom I had been privileged to meet when he visited the Houses of Parliament in London, hosted by Tim Loughton, a member of Parliament and chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Tibet. The Speaker of the House of Commons at the time, John Bercow, attended the meeting and was presented by the Sikyong with a khata, the traditional Tibetan white ceremonial scarf. Talking with Penpa Tsering in what is often described as the best restaurant in Rome, alongside Parliamentarians from around the world at a gathering of the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China (IPAC) on the eve of the G20 summit, I was struck by the humility, dignity, and quiet determination of the Tibetan leader. We talked informally over a five-course traditional Italian dinner about the current situation in Tibet, the Chinese regime’s increasing aggression beyond its borders, and what the world should do to confront Beijing. After over seven decades of struggle, he—and all Tibetans—know more than anyone else that when you resist the Chinese Communist Party, you have to be prepared to be in it for the long haul.

The Sikyong’s role was only established in 2011, when the Dalai Lama announced his decision to relinquish his political leadership and become solely a spiritual leader. Until then, Tibet’s exiled political administration, known in Tibetan as the “Kashag,” was run by the holder of the office of “Kalon Tripa,” subordinate to the Dalai Lama. The first direct elections for this office were held in 2001, and ever since then the Tibetan community in exile in Dharamsala, in India’s northern state of Himachal Pradesh, as well as the Tibetan diaspora around the world, have organized democratic elections for their leaders. The term “Sikyong,” according to Tibetan Review, means “political leader,” and had previously been used by regents who ruled Tibet during the Dalai Lama’s minority. According to the former foreign minister of the Tibetan government-in-exile Kalon Dickyi Choyang, the term “Sikyong” dates back to the time of the seventh Dalai Lama, from 1708 to 1757, and that using this title “ensures historical continuity and legitimacy of the traditional leadership from the fifth Dalai Lama.”

The evening following my conversation with the Sikyong, a group of Tibetan women living in Italy came to present me with my first-ever khata. I bowed my head as they placed it on my shoulders, and as I did so a feeling of deep and profound respect for the Tibetans filled my heart. Throughout my years of working on human rights in China, I had, of course, always been concerned about Tibet, protested alongside Tibetans, spoken at seminars organized by Tibetan human rights groups, and collaborated with groups such as Free Tibet. But whereas I had travelled widely throughout Mainland China and lived in Hong Kong, I had never visited Tibet, and, it is fair to say, I had not been as active in in-depth advocacy for Tibet as I had been for Hong Kong, the Uyghurs, persecuted Christians, Falun Gong practitioners, and human rights defenders in China. Yet I was becoming acutely and increasingly conscious of the need to ensure that as all the other human rights concerns in China—especially the Uyghurs and Hong Kong—receive more attention, and rightly so, around the world, we must not allow Tibet to be forgotten.

Ever since 40,000 People’s Liberation Army (PLA) troops crossed the Yangtze and marched into Tibet in October 1950, Tibet has been under brutal repression and occupation. The previous year, just after Mao Zedong and the Chinese Communist Party seized power in China, they declared their intent with a radio broadcast which, according to Sam van Schaik in Tibet: A History, “stated that Tibet was an indivisible part of China, and anyone who failed to recognize this would ‘crack his skull against the mailed fist of the PLA.’” In January 1950, van Schaik notes, Mao told Joseph Stalin in Moscow of his plan to conquer Tibet, and Stalin pledged his support. The Tibetan government was already aware of the danger and had appealed to the international community for help. The British, who had invaded and occupied Tibet from 1903 to 1904, washed their hands of it. “The Tibetans’ first hope centred on their old allies, the British,” writes van Schaik. “But after withdrawing from India, the British wanted no further entanglement with Tibet; they merely suggested that Britain’s old interests in Tibet were now a matter for the newly independent Indian government. For their part, the Indians were keen to forge a close relationship

Tibet had an army, and was determined to fight the invaders, but they were totally outmanned and outgunned. A Tibetan government official, Ngapo Ngawang Jigme, in van Schaik’s words, “told anyone who cared to listen that Tibet had no hope of fighting off the Chinese. He was by nature a diplomat rather than a general, but his assessment of Tibet’s chances was realistic.” Tibet was not, argues van Schaik, “a nation of pacifists,” but without significant international support, it was impossible to resist.

Mao was motivated not only by communist ideology, according to van Schaik, but by national pride. “China had suffered one humiliation after another during the previous century, at the hands of the British, the Japanese and other foreign powers… If China was to stand up for itself again, it was vital to begin by reasserting control over Tibet.” In 1959, the Dalai Lama finally fled Tibet, beginning the rest of his life in exile in McLeod Ganj, a suburb of Dharamsala, the old British hill station in India. As he writes, for almost a decade he had stayed in Tibet and worked hard to establish peace with China, even though it had “sent an army to invade my country,” but “the task proved impossible.” With great reluctance, he “came to the unhappy conclusion that I could serve my people better from outside.”

In comments His Holiness graciously delivered to me for this book, the Dalai Lama reflected on the significance of his over seven decades in exile. “Since I became a refugee, I have thought of myself as a citizen of the world,” he told me. “I made this clear in the 1970s when Mark Tully, the long-time BBC correspondent in Delhi, asked me why I wanted to travel abroad. Since I came into exile, I have enjoyed the freedom to travel the world, mainly at the invitation of educational institutions and organizations committed to peace.” His Holiness explained that he considers “being mindful of the oneness of humanity and cultivating a sense of universal responsibility to be more important than allegiance to a particular nation state or community of people.” As a Tibetan, the Dalai Lama feels “a strong responsibility to protect Tibetan culture, which, with its focus on compassion and doing no harm, has a huge potential to contribute to peace and understanding in the world.”

His Holiness emphasized to me that “we are not seeking separation from the People’s Republic of China.” Instead, he advocates what he calls “a Middle-Way Approach,” whereby Tibet remains within China’s sovereignty but enjoys a high degree of autonomy and self-rule. “I firmly believe that this would be of mutual benefit to Tibetans as well as to the Chinese,” he told me. “With China’s assistance, we Tibetans will be able to develop Tibet, while at the same time keeping alive our own unique Buddhist culture, as well as preserving Tibet’s delicate environment. If China were to resolve the Tibet issue peacefully, taking mutual interests into account, it would strengthen its own unity and stability. Meanwhile, as increasing numbers of Chinese, Buddhists, and scholars are taking an interest in Tibet’s rich Buddhist culture, this is something we can offer to them.”

In life, said His Holiness, “we naturally face difficulties.” But we should not allow ourselves to become “demoralized” or “discouraged,” Instead, he argued, “we can always use our intelligence and look at whatever complication besets us from a wider perspective. We have this marvellous human brain and we should use it with determination.” His lifelong commitment, he added, is to “raise aware-ness that the most important source of happiness lies within us and that warm-heartedness is that source of happiness.”

In their Tibet Brief 20/20, two international law experts, Michael van Walt van Praag and Mike Boltjes are unequivocal in their conclusion that China’s presence in Tibet is “unlawful.” Despite the historical interactions between Tibet and China over the centuries—from 1912 until the invasion in 1950—they argue, “Tibet was an independent state de facto and de jure.” Furthermore, “contrary to what the People’s Republic of China (PRC) claims and to what many people take for granted, Tibet was historically never a part of China… Tibet is an occupied country and the PRC does not possess sovereignty over it. This calls for an immediate course correction to bring government policies in compliance with international law.”

Not only is Tibet occupied, it is brutally repressed. As van Walt van Praag and Boltjes note, “the PRC not only illegally occupies Tibet, it also denies the Tibetan people their lawful exercise of self-determination. This denial, the PRC’s active opposition to any expressions of it, and its modifications of administrative boundaries of what are now the Tibetan autonomous region, prefectures and counties, all constitute violations of fundamental norms of international law.”

In 1959, the International Commission of Jurists published a report which concluded that China had illegally invaded and occupied Tibet, and that there was a prima facie case of genocide. The Dalai Lama recounts that “it was not until I read the report published in 1959 by the International Commission of Jurists that I fully accepted what I had heard: crucifixion, vivisection, disembowelling, and dismemberment of victims was commonplace. So, too, were beheading, burning, beating to death, and burying alive, not to mention dragging people behind galloping horses until they died or hanging them upside down and throwing them bound hand and foot into icy water. And, in order to prevent them shouting out ‘Long live the Dalai Lama,’ on the way to execution, they tore out their tongues with meat hooks.”

Extracted with permission from the book, “China Nexus: Thirty Years in and Around the Chinese Communist Party’s Tyranny”, by Benedict Rogers and published by Optimum Publishing International, Toronto.

Benedict Rogers is a human rights activist and writer specialising in Asian policy and geopolitics. He is the co-founder and Chief Executive Officer of Hong Kong Watch, an advisor to the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China (IPAC), the Stop Uyghur Genocide Campaign and several other charities, and Deputy Chair of the UK Conservative Party Human Rights Commission.