Those stunning memories of Kashmir flooded back two months ago when I was following an Early Day Motion in British Parliament on the “Annexation of Gilgit-Baltistan by Pakistan as its Fifth Frontier”. It is so important that the Motion is worth citing in full. “That this House condemns the arbitrary announcement by Pakistan declaring Gilgit-Baltistan as its Fifth Frontier, implying its attempts to annex the already disputed area; notes that Gilgit-Baltistan is a legal and constitutional part of the state of Jammu and Kashmir, India, which is illegally occupied by Pakistan since 1947, and where the people are denied their fundamental rights including the right of freedom of expression; further notes the attempts to change the demography of the region in violation of State Subject Ordinance and forcibly and illegally to build the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which further aggravates and interferes with the disputed territory.” Clearly, this move by Pakistan is seen as consolidating a land-grab for political, geographical and economic reasons.

The $62 billion CPEC, a collection of infrastructure projects intended to rapidly modernise Pakistani infrastructure and strengthen its economy by the construction of modern transportation networks, numerous energy projects and special economic zones, is linked to the polarisation of policy, which appears to be developing across the world. On the one hand there is President Donald Trump declaring America First, arguing that globalisation has brought American citizens more pain than gain, and in his first week in office, scrapping the Trans Pacific Partnership between the 12 countries around the Pacific Rim. On the other hand, China’s President Xi Jinping is promoting the concept of a new Silk Road, with his One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative, introduced in 2013 and designed to promote more globalisation; the exact opposite to Trump’s current policy and designed to fill the void left by him. During the gathering of some world leaders and representatives in Beijing this month, Xi hailed OBOR as the “project of the century” and pledged at least $113 billion to it, urging countries around the world to join hands with him in pursuit of globalisation. China has identified some 65 countries along the belt and road which it hopes will participate, representing 62% of the world’s population and 30% of its economic output. Already 47 state owned enterprises are carrying out some 1,700 projects in these countries. A collection of Chinese banks and multilateral institutions will be major financiers of the project, but many analysts have warned of the high risk associated with OBOR, with the possibility that significant sums could be lost.

A collection of Chinese banks and multilateral institutions will be major financiers of the project, but many analysts have warned of the high risk associated with OBOR, with the possibility that significant sums could be lost.

For this reason, the European Union (EU), although broadly welcoming the OBOR initiative, displayed extreme caution by refusing to sign China’s trade statement, expressing concerns on its economic and environmental viability. The EU also insisted on a fair tendering process, with some countries showing considerable scepticism about China’s true intentions of shifting its excess industrial capacity to less developed nations and drawing poorer countries tighter into Beijing’s economic grip.

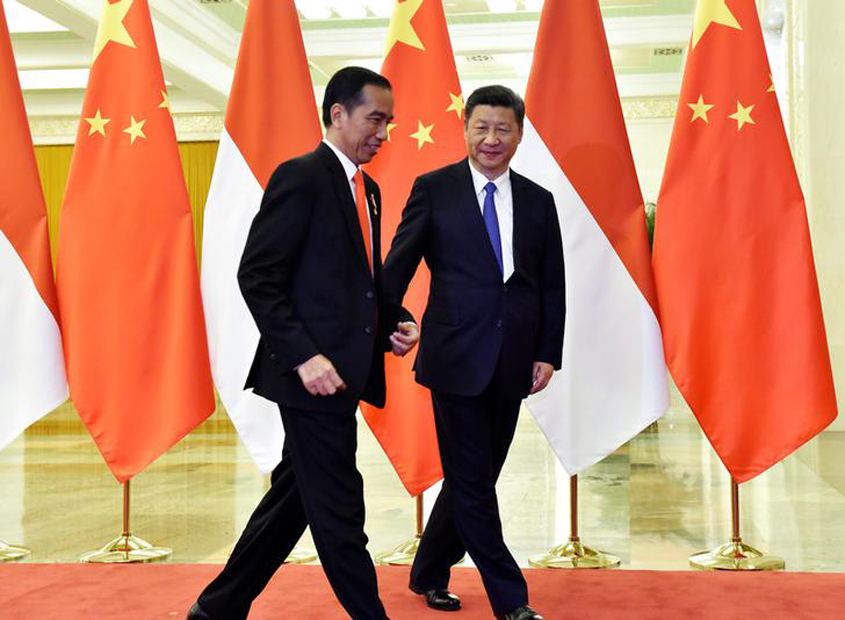

The extent to which non-Chinese countries would have any involvement in OBOR projects remains unclear, with the fear that it could turn into a Chinese construction blitz. Sensitive to these concerns, Beijing hit back by saying that the project is “not and never will be neo-colonisation by stealth. China harbours no intention to control or threaten any other nation. China needs no puppet states!” However, with plans for a pipeline and a port in Pakistan, bridges in Bangladesh, railways to Russia, high speed rail link in Indonesia, an industrial park in Cambodia and a $1.1 billion port project in Sri Lanka, the jury is out on who gains the most from this construction and the subsequent control. According to some commentators, the constant reference by Xi to China undergoing a “great rejuvenation” has a hint of revanchism in the region, being seen as a desire to re-create a regional hierarchy, with China at the top.

There is, of course, an optimistic and positive view of OBOR, argued strongly in this newspaper. It is almost 30 years since the idea of the 21st century being

John Dobson worked in UK Prime Minister John Major’s Office between 1995 and 1998 and is presently a consultant in the private sector.