Traditionally a friend, India has been viewed with suspicion since the civil war.

Since its independence in 1948, Sri Lanka (previously known as Ceylon) and India have enjoyed healthy bilateral relations with strong economic ties and consistent stands on most international issues. The leaders of both nations stood side by side in the founding and growth of the non-aligned nations’ movement during the Cold War years. They usually went along with one another, despite the vast differences in size, geography, and population, in facing the multifaceted challenges of development. With commonality in ethnicity between the residents of its Northern Province and the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, strong language and cultural connections exist. The following of Buddhism has helped grow the cordiality. The relationship, however, has gone through a degree of volatility ever since a civil war began in the early 1980s in the island nation.

In a prolonged armed conflict between the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), a separatist insurgent force concentrated in the Jaffna region of the Northern Province, and Sri Lankan forces dominated by Sinhalese troops, India has often found itself at a crossroad. It has had to face the dilemma of protecting the interests of 1.6 million persons of Tamil origin, who had become citizens there long ago, or supporting the hitherto friendly government of the neighbouring country. In line with the political pressure exerted by the sizable number of domestic Tamilians, India’s stance vis-à-vis the two sides has wavered. In 1987, when the Sri Lankan government imposed an economic blockade of Jaffna to quell the uprising by LTTE, the Indian government chose to extend support to the rebels and air-dropped essential food and medicines. Upon brokering a deal between the warring parties in a foreign land, in July 1987, India signed a peace accord with the Sri Lankan government, termed the 13th amendment to the Constitution. It assigned a degree of regional autonomy in the Tamil areas with the Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front (EPRLF) controlling the regional council. The agreement called for the Tamil military groups to lay down their arms. To enforce disarmament and oversee the regional council, India sent a large military contingent called the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF). While most Tamil groups accepted the accord, LTTE had refused and also declined to hand over its arms. Consequently, the IPKF ended up in a military conflict with LTTE.

Almost three years later, in March 1990, the new Indian government of Prime Minister V.P. Singh withdrew the force, even though LTTE was still continuing to fight. The bloody civil war ended 19 years later in 2009, by which time the Sri Lankan army and air force had been replenished with arms and aircraft from the West. During the intervening years, the Indian government supported the peace process but remained a spectator to the indiscriminate killings of Tamilians, including civilians, by the government forces.

India’s shifting stand during the civil war didn’t bode well, despite the loss of 1,115 soldiers. The reputational loss of its large army being unable to achieve the mission of ending the insurrection overshadowed any gains. India failed to garner approval from the Tamilians in Sri Lanka or India. In fact, its military intervention became a stated cause for the assassination of former Premier Rajiv Gandhi in 1991. Even more concerning was that India’s actions raised suspicions in Sri Lanka about its intentions. Questions arose, albeit not vociferously, about India taking up the cause on behalf of people of Indian origin who had long ago become citizens of another country.

The cooling off in bilateral relations since the first decade of the current century coincided with China’s rise as a regional and thereafter a global superpower. As part of its “pearls in a string around India” policy, China approached Sri Lanka with its newly acquired economic might, making attractive offers to assist in the economic recovery of the war-battered nation. Besides arming its navy, China extended large sums as loans to rebuild and expand capital-intensive ports and highways, starting in Colombo and later in Hambantota and now including the construction of the Outer Circular Highway. However, with the anticipated traffic build-up not materializing and a lack of sufficient toll income, debt servicing became challenging. This situation provided Chinese lenders for the Hambantota port, the right to convert the outstanding loan into equity and take over the underlying land rights for 99 years. Consequently, a Chinese flag now denotes sovereignty at the port, with the rights of Sri Lankans to enter the facility significantly curtailed. All types of ships, including naval and “research” vessels (a euphemism for Chinese spy vessels), ply to and from this strategically located port very close to the Indian waters. Given Sri Lanka’s precarious economic health

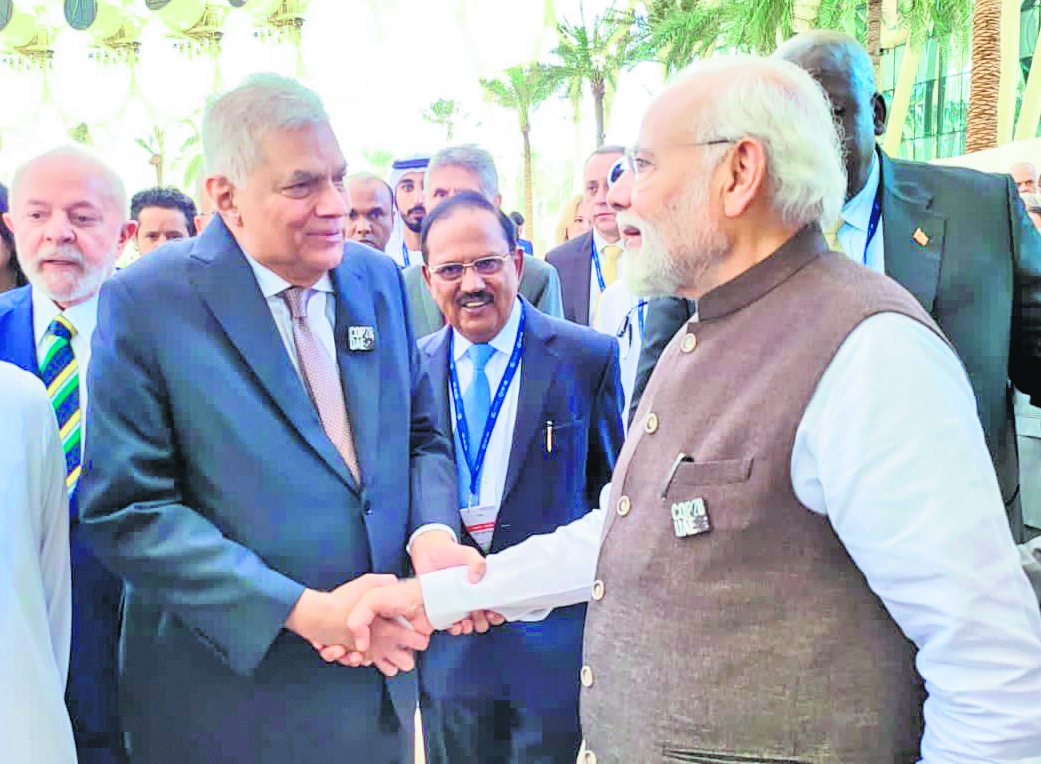

While India may not match China’s “munificence”, it has done well in assisting Sri Lanka in managing its severe economic crisis by promptly extending $3.8 billion worth of new lines of credit since last year. These credits have helped replenish foreign currency reserves and facilitated the purchase of essential commodities such as food, medicines, fuel, and fertilizers. India has also advocated a liberal IMF aid package for Sri Lanka, being the first country to agree to restructure its pending debt of $1 billion. During the visit of Sri Lankan President Ranil Wickremasinghe to India in July of this year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi assured continuing assistance and outlined a vision for further collaboration in maritime and air connectivity, energy, as well as new initiatives in tourism, power, trade, higher education, and skill development. The leaders agreed to link their electricity grids and explore the feasibility of constructing a petroleum refinery in Sri Lanka besides a bridge across the Palk Strait to connect the two nations. Earlier, Sri Lanka had permitted India to establish an oil storage farm at the eastern Trincomalee port and 600 MW of solar power generation facilities in two Sri Lankan islands off the Indian coast.

Bilateral trade between the two countries had consistently grown to almost $5 billion by 2018-19, with India being Sri Lanka’s largest trading partner. Before the Covid-19 pandemic, there was a cumulative inflow of $1.25 billion in foreign direct investment from India. Additionally, official Indian development assistance worth $3 billion, including $560 million in grants, has been provided in various fields such as healthcare, housing, railways, student stipends, and cultural promotion.

The broadening of India’s understanding of Sri Lanka can be translated into an increase in aid, as well as other positive actions, a gesture that would be particularly appreciated at this juncture. Bilateral trade, which significantly expanded after the signing of a Free Trade Agreement in 2000 covering 60% of products imported by Sri Lanka from India, has the potential to be further multiplied. The establishment of a more comprehensive Economic & Technological Trade Agreement has been under discussion since 2010. The Sri Lankan President, during his visit last July, hinted at its potential utility. India should respond affirmatively to enter into such an agreement covering not just trade but also capital flows, including foreign direct investment, movement of workers, and intellectual property rights. A more extensive adoption of rupees for trade settlement is also warranted. A compassionate approach towards the beleaguered nation, with its fundamentals relatively intact, should significantly contribute to the development of sustainable relations.

Sri Lanka and India must also resolve their differences over fishing, especially in the Palk Strait, which, at certain points, is barely 20 kilometres wide. Traditionally, Indian fishermen remained within their territorial rights, i.e. 12 miles or 19 kilometers from the Indian coast, when venturing into the sea. However, the use of mechanized trawlers by affluent fishermen has led to transgressions of this distance threshold. Consequently, Sri Lankan police and naval boats frequently pursue and detain Indian fishermen entering its territorial waters. Over the years, more than 700 Indian fishermen have been killed in firings from Sri Lankan patrol vessels. Sri Lanka’s response to India’s appeals for greater understanding has typically been discouraging. While emphasising the need to protect its own fishing interests, it suggests that Indian fishermen should avoid using trawlers. Additionally, Sri Lanka cites security concerns, and the potential for smuggling contraband as reasons for its navy checking the ingress into its waters. Resolving this issue is crucial for fostering improved relations between the two nations.

While Sri Lanka’s concerns undoubtedly merit consideration, this minor persisting issue should not be allowed to remain a major bone of contention. A more effective deployment of the Indian coast guard could redirect Indian mechanized boats into the open seas, preventing them from entering the narrow waters of the Palk Strait. It must be kept in mind that mutual larger interest lies in enhancing connectivity, potentially through the construction of a bridge over the strait that could facilitate trade via trucks instead of costlier shipping. Moreover, the navies of both countries need to develop greater coordination in patrolling the sea routes through the strait and in the Indian Ocean, thereby ensuring smoother maritime activities. Cooperation and coordination are essential for resolving the extant easily resolvable differences and promoting harmonious long term relations between the traditionally friendly neighbours.

Dr Ajay Dua is a former Secretary of the Union Ministry of Commerce & Industry.

Two more articles on country-specific strategies will follow.