Restricting commercial relations with China isn’t the best choice.

It is becoming increasingly apparent that the prevailing perceptibly slower rate of growth in China is likely to persist for a while. While this is concerning and requires action on several fronts, it doesn’t necessarily connote there will be an economic crisis. China’s economy, which is enormous at $19.3 trillion (second only to the US at $26.8 trillion), remains fundamentally intact. Informed assessors around the world continue to be sanguine about China’s long-term prospects.

This belief is not unfounded. Even though China faces challenges like slowing GDP growth, rising youth unemployment and a real estate industry struggling to avoid a collapse caused by its vast debts, its overall country rating, and consequent ability to access global capital markets should not get seriously impacted. Almost all the funds involved in the beleaguered activity have been domestically sourced. Through the government controlled central bank and the State owned lending institutions, the establishment there can be expected to rein in the situation; the remedial measures may include reducing their exposure to the real estate industry and increasing upfront payments by house buyers, besides facilitation of overall bank-lending by lowering the cash reserve requirements. Hitherto, a portion of it had necessarily to be in foreign currency.

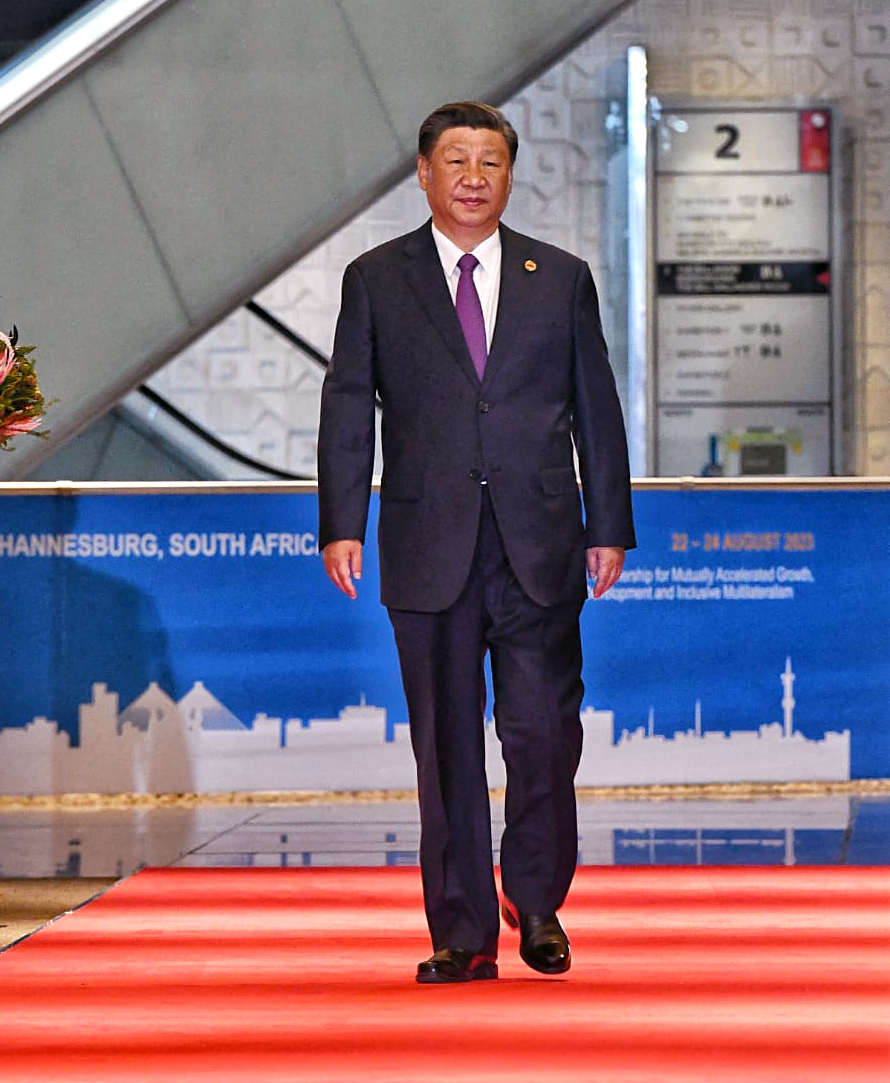

A more significant change in the national development approach is being quietly effected by President Xi Jinping with the endorsement by the all-pervasive Communist Party. After over four decades of pursuing the Deng Xiaoping approach of growing the national GDP with increasing involvement of the private sector, the emphasis is now on achieving “common prosperity,” with the State playing a greater and a more prominent role. China has already lifted many citizens out of extreme poverty, and its per capita income of around $12,000 puts it firmly in the middle-income category. The not so explicitly stated new goal is to significantly reduce income and wealth inequality among its citizens, a sine quo non of socialism. To achieve this, it is likely to launch new initiatives to develop rural areas and encourage people to stay there instead of migrating to cities. Xi’s efforts to push the graduating university students to “taste bitterness” of the village life and seek employment opportunities there reflect the new thinking.

Greater purchasing power flowing into the hands of the middle class and those below, should help step up the aggregate domestic consumption of the economy. While the need and significance of this has been flagged repeatedly, progress in materialising it has been marginal. The over-dependence upon exports, at times accounting for 40% of GDP, has persisted, as has the over-weightage of capital formation. The latter no doubt drives the future growth prospects, but it tends to come at the cost of the present generation and its well-being. The less well-off have a higher propensity to spend than save relative to the affluent. The intended more egalitarian strategy should assist in reducing the vulnerability of the Chinese economy to external factors, and necessarily make it more inward-looking.

It is under such future projections, the US and several developed nations are leaning towards a change in tack towards China, despite its assertiveness and intransigence in its territorial and geopolitical ambitions. They no longer favour a confrontational approach over a more conciliatory one. Without compromising on security considerations, they seem inclined to consider greater accommodation on commercial and financial matters. Distinguishing between these two aspects of the relationship is a pragmatic way forward given their considerable mutual interdependence, and the potential impact of China’s decline upon global trade and the global GDP growth . Continued bellicosity on either side is also bound to impact the warranted coordination in the more important and existential issue of climate change. The process of negotiations and effecting the implementation-arrangements could, at times, be long-winded and accompanied by hiccups, but remains worth the while.

Turning to India, it has to be acknowledged that the situation for it is perceptibly different from the distant US and the European nations. Part of Indian territory, viz Aksai Chin in Ladakh, and smaller pockets on the eastern border, are under Chinese occupation. The aggressive neighbour has questioned the validity of the McMahon Line, hitherto serving as the international border since 1913. To convey that message forcefully, the Chinese People’s Army had, in 1962, marched into the North East Frontier Agency administered area (now renamed Arunachal Pradesh), reaching up to Tezpur in Assam. Though it vacated the occupied area soon after, 100 odd periodically held bilateral parleys have not helped resolve the vexatious matter.

China also continues to use its veto power to thwart Indian aspirations to become a permanent member of the UN’s Security Council. Similar hostile stances are being regularly taken by China in other international fora to favour itself or its close ally Pakistan, India’s foe on the western front. China views only itself as the sole Asian power of consequence, and challenges India’s aspirations to share the podium. India becoming more active in alliances like the Quad and developing closer relationships with the United States or its allies, have further antagonized China. President Xi’s withdrawal, at the last moment, from the G20 meet in New Delhi is one further move to deny any advantage to burnish its global image.

In evaluating how India should position future economic relations with China, the above security situation must not be underplayed. China’s intention to further expand its geographical jurisdiction at any cost is totally unacceptable and must be checked with all resources in India’s command and reach. A material limitation on commercial relations is also the reality that over the last forty years, when compared to India, China has become a much larger and diverse economy with tremendous capabilities to produce both simple and modern technology-based products and services alike. India’s natural resource endowment, both in ordinary and critical rare metals, is also lower than that of China. In matters of bilateral trade, capital, and technology flows, China’s needs are much less pressing than India’s.

At $115.83 bn, the China-India bilateral trade in 2021 was 34% higher than in the previous year. The Indian imports, which constitute about three-quarters or more of it, have consistently grown more rapidly than its exports. India’s imports include many fundamental items such as electrical machinery, equipment, nuclear reactors, boilers, electronic components, computer hardware, and peripherals. Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) for the vast Indian formulation drug industry come from China, as do several chemicals and other raw materials for the manufacture of solar cells and panels. Lithium-ion batteries for the expanding EV industry are sourced from there. Several less advanced semiconductors fitted into various appliances, ICE-based automobiles, and mobile phones also have Chinese origin. The Production Linked Incentive (PLI scheme) under the Make in India mission envisages localization of such products, but its full impact will kick in after a certain gestation period. The relative inexpensiveness of Chinese products, raw materials, and components vis-à-vis other sources, and even those manufactured in India, remains an important consideration when weighing India’s high Chinese dependence.

Indian exports to China are in items such as mineral ores (primarily iron), marine products, organic chemicals, and petroleum products. In value, these add up to a fraction of its annual imports. Furthermore, the Chinese dependence upon India for such exports is no longer of a permanent nature since it can procure these from elsewhere. Indian vendors would be tapped only as long as the Chinese derive distinct advantages, be it by way of price, quality, or delivery schedules.

Despite various import substitution efforts and free trade agreements with Asian countries, India’s dependence on China persists. No doubt , such a dependency remains a global issue, with China a crucial trading partner for all, despite calls for countries to adopt a China-plus-one strategy. For 15 years, China has been India’s top source of imports, with its share rising from 11% to 16%. Excluding crude oil, Indian imports from China constitute 25% or more of its total imports. This stickiness in trade patterns has resulted in a high and widening current account merchandise deficit for India—currently in excess of $90 bn. In the first half of the current year, while China’s exports declined by 12.4%, Indian imports decreased marginally by 0.9% to $56.53 billion, and exports fell by 0.6% to $9.49 billion. The trade deficit for H1 was $47.04 billion. The high volume and critical nature of India’s imports from China are central to its China strategy.

To continue to be able to access its essentials from

Another area where India faces challenges is capital flows, particularly equity investment. Chinese interest in investing in India primarily revolves around industries targeting the large Indian market, such as pharmaceuticals, electric vehicles, and digital services including the payment platforms. Recently, due to security concerns, India imposed severe restrictions on foreign direct investment (FDI) from China. The resultant uncertainty surrounding FDI clearances has frustrated investors, especially as investments from Hong Kong-based firms are also affected. While security concerns in areas like defence, infrastructure, power, and telecom are crucial and must remain, more transparency could be introduced in less sensitive sectors. Establishing maximum processing times for approval or rejection, along with explanations, would be beneficial for applicants.

Recognizing China’s distinct advantages and incorporating them into India’s response to the evolving situation should not be viewed as India conceding to its northern neighbour. Instead, it represents a pragmatic and intelligent approach to safeguarding India’s current and future national interests.

Dr Ajay Dua is a former Union Secretary of Commerce & Industry.