India’s Amrit Kaal is to be viewed beyond a national vision to be a practical blueprint for global good that would enable the country to take up its proper role as a spiritual guide, as envisioned by Aurobindo.

“You have the word and we are waiting to accept it from you. India will speak through your voice to the world.”

Rabindranath Tagore

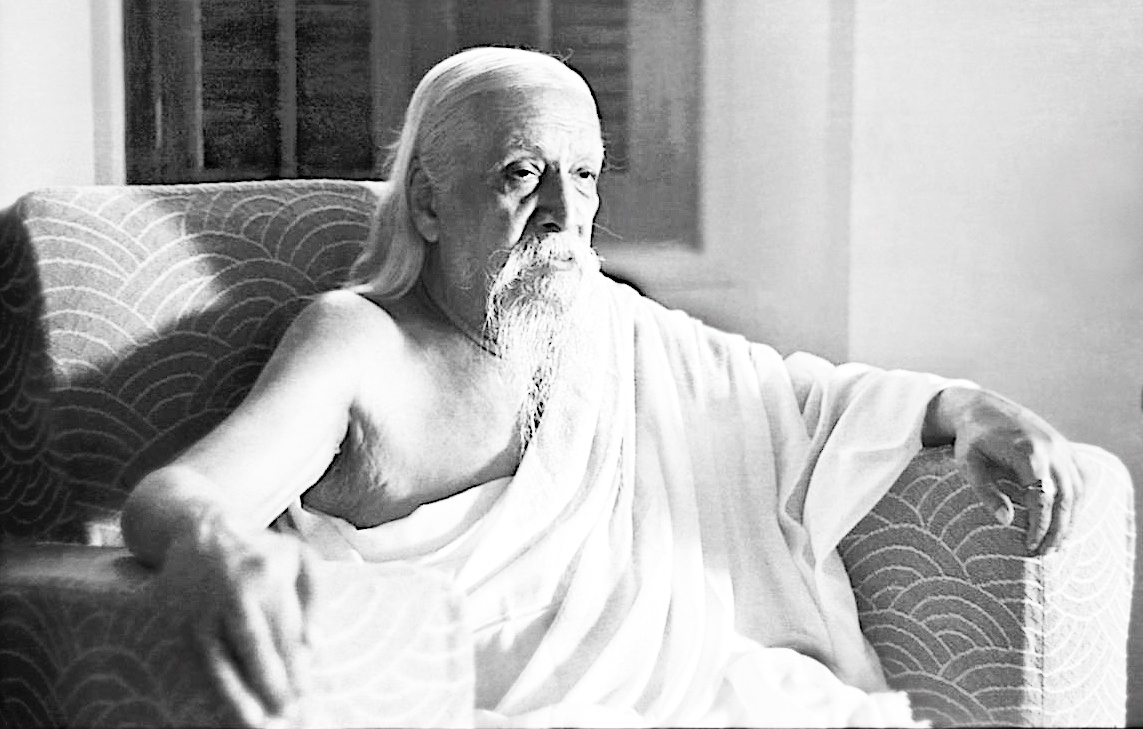

An early advocate of radical political thought, Aurobindo sought to end British rule. However, his legacy as a profound philosopher, who contributed to conceptualizing India as a nation-state is invaluable. Today, as India stands at a critical juncture in history, Aurobindo’s works offered a unique blueprint for a strong, self-aware India that intertwines political activism with its spiritual and cultural heritage.

He became a leading figure in the revolutionary movement. He used to write fearless analytical articles for the English newspaper “Bande Mataram”. He also started the weekly English journal titled “Dharma”. In his publications, Aurobindo tried to convey the message of Swaraj or freedom from British rule. He was one of the founders of the youth club Anushilan Samiti, which protested against the atrocities of the British government. He later had to go to jail in a case connected with the Anushilan Samiti.

AUROBINDO, THE NATIONALIST

Aurobindo was born in India but was educated in England, where he developed his political beliefs, drawing inspiration from Irish and Italian nationalists. These early events made him develop a keen interest in the independence of India, which he brought with him back to India in 1893. In Baroda, where he took up a government job, Aurobindo delved deeply into Indian history, philosophy, and Bengali literature as a civil servant. This period of reflection shaped his nationalist and spiritual philosophies, leading to his pivotal contributions to the freedom movement.

His ideas of Swaraj (self-rule) and boycott of British goods became fundamental to India’s struggle for freedom from colonial rule. His fusion of political action and philosophical reasoning provided the intellectual basis for building an independent and sovereign Indian nation. Aurobindo left his job at Baroda following the partitioning of Bengal by the British in 1905 as part of their strategy to divide Indians, which affected him deeply. Still, he took off from politics shortly and moved to Puducherry, where his significant works were produced.

AUROBINDO’S IDEAS

Aurobindo Ghosh was not just a freedom fighter; he was more concerned with diverse problems about humans, the origins of the universe, and the development of higher human values. His philosophical expedition took into account notable European philosophers as well as Indian spiritual traditions, which include the Upanishads, Gita, Ramakrishna’s teachings, and those of Vivekananda. This is recorded in his best-known works such as, “The Life Divine”, “The Synthesis of Yoga”, and “Essays on the Gita”, where Aurobindo combined ideas from Western materialism and the idealistic traditions of Indian philosophy to produce one unique worldview.

Aurobindo’s understanding of Indian intellectual history was both profound and subtle, allowing him to create a philosophy that connected the physical world with the metaphysical one. His inquiry focused on fundamental questions regarding how the universe began and what it is now like. He said that this world consists of matter that evolves through different levels, starting from simple plant forms to animals and then to the human mind, ultimately culminating in what he called the “supermind.”

Aurobindo believed that matter is, in essence, spirit in a latent form, gradually evolving toward the revelation of the spirit, which he identified as the supreme and absolute reality. According to Aurobindo, the journey from mind to supermind is a process of spiritual transformation, and yoga is the key technique to accelerate this process. He introduced the concept of “Integral Yoga” (Purna Yoga), which synthesizes the techniques of four traditional yogas: Karma (action), Bhakti (devotion), Jnana (knowledge), and Raja (meditation). Through this Integral Yoga, an individual can ascend to the “supramental level,” achieving a state of ultimate joy (Ananda), which Aurobindo saw as crucial for self-realization and the service of humanity.

Aurobindo’s philosophy emphasized that “matter” and “spirit” are not separate entities but are interconnected in a process of gradual evolution, where matter transforms into pure spirit. This perspective allowed him to reconcile materialism with spiritualism, arguing that human endeavours should be directed toward perfecting the spiritual aspect of existence, which would ultimately benefit humanity as a whole. His vision was one of holistic progress, where the material and spiritual dimensions of life are integrated in the pursuit of human development and the realization of higher consciousness.

SPIRITUAL NATIONALISM

Central to Aurobindo’s vision was the concept of Spiritual Nationalism. This idea, built upon the works of the great Bengali novelist Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay, was expanded by Aurobindo, who argued that a nation cannot be understood merely in terms of its landmass or population. For Aurobindo, India was akin to a mother, as he often referred to Bharat as the Mother Goddess. He urged young Indians to strive for the nation’s freedom, not merely as a political or geographic entity, but as something more profound and ethereal—their mother. Given India’s situation at the time, Aurobindo believed that liberating the motherland was the most urgent duty of her children, one that demanded any sacrifice necessary.

Aurobindo regarded the nation as a mighty “Shakti,” a living entity composed of millions of constituent parts. His numerous poems and articles from this period delve into the details of this idea, offering a new dimension to the understanding of nationalism—a spiritual one. He conceptualized that India’s independence is necessary for it to become the spiritual leader of the global community. Aurobindo considered nationalism to be a form of “religious sadhana,” arguing that “nationalism is a religion by which people try to realize God in their nation and their fellow countrymen.”

He believed that Hindu Sanatana Dharma embodied a universal philosophy—open, diverse, and inclusive of different practices and views. According to him, it is through individual self-realization that one can contribute to the broader process of national and spiritual development. For Aurobindo, India’s independence was a necessary precursor for the nation to assume its destined role as a spiritual guide for humanity.

RELEVANCE TODAY

India’s Amrit Kaal, therefore, is to be viewed beyond a national vision to be a practical blueprint for global good that would enable the country to take up its proper role as a spiritual guide, as envisioned by Aurobindo. The speech by Prime Minister Narendra Modi on 15 August 2024 has all these elements, including the elements about India’s future and its emergence as a peaceful, global force for good. From Aurobindo’s view, such vision entails synthesizing vision with action. Thus, Bharat is a nation of seekers rather than ideologues. To truly respect Aurobindo, we must strive to make Amrit Kaal come true so that India becomes an influential political and economic power spiritual leader.

Prof Santishree Dhulipudi Pandit is the Vice Chancellor of JNU.