The Chinese Revolution directly impacted Chinese authority in Tibet.

Tibet’s tempestuous political history and upheavals of its past are well recorded and archived. The 14th (present) Dalai Lama arrived in India on a yak by crossing the border at Khenzimane on 31 March 1959, travelling a fortnight after leaving Lhasa perhaps during the darkest phase of his last night spent in his homeland. Upon arrival in India, the first Indian post was at Chuthangmu, north of Tawang (then part of Kameng Frontier Division). Once past the Indo-Tibetan border, the Assam Rifles accorded him a guard of honour in Tawang and escorted the Dalai Lama. Following a stay in Bomdila, the Dalai Lama travelled to the hills of northern India and set up the Tibetan Government-in-exile on 29 April 1959. It is 60 years since his passage to India, and over a century of India’s deeply rooted relationship with Tibet.

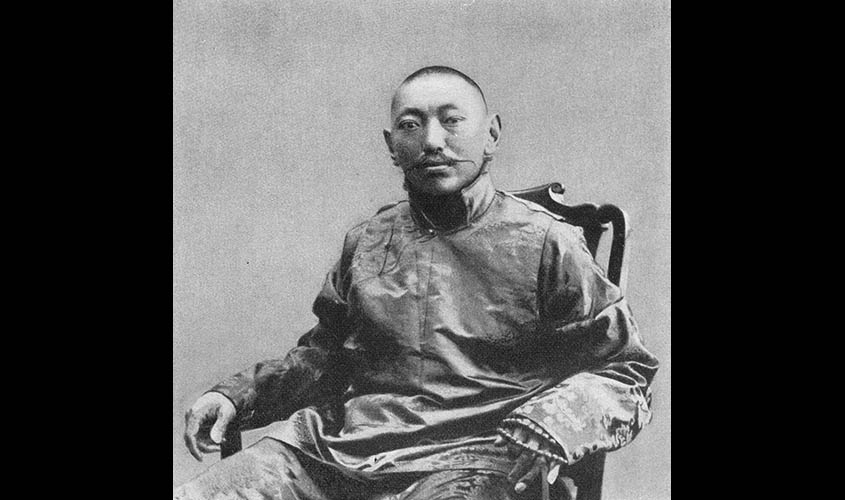

Prior to the present Dalai Lama, his predecessor, the 13th Dalai Lama (1876-1933) fled first to Mongolia in 1904 and thereafter to China. Upon his arrival in Peking, the Chinese did not accord him the same honour that his antecedents had received by the previous Mongol emperors. From the earliest times, the political relations existing between Tibet and China were based primarily on the special personal equation shared by the Dalai Lamas with the Mongol emperors. With the collapse of the Manchu dynasty in 1912 following the Chinese rebellion, the relationship ceased to exist.

Sensing that its position inside Tibet was getting stronger China planned to conquer and control Tibet. To deflect attention, Peking conveyed to the Tibetans that the approaching Chinese troops intended to protect the Tibetans against the British. By 1909 the new Chinese military administrator Chao Erh-feng was actively pushing troops towards Lhasa launching attacks in three Tibetan provinces.

Upon the 13th Dalai Lama’s return to Tibet from China, Chao—appointed “Resident of Tibet”—was known to be committing excesses through his troops, including destroying monasteries, looting monastic properties and tearing up sacred books. It was during this stint that the 13th Dalai Lama met Charles Bell, whose work Portrait of The Dalai Lama published in 1946 is amongst the finest accounts on Tibet and its chequered history.

Bell chronicles personal conversations with the 13th Dalai Lama, in which the latter described how the Chinese military

Subsequently, the Chinese Revolution of 1912 overthrew the Qing (Manchu) dynasty and created a republic with a provisional Constitution promulgated by the Nanjing Parliament, and the government transferred to Peking. This was also the time when the 13th Dalai Lama returned from India to Tibet. The Chinese Revolution directly impacted Chinese authority in Tibet. The strains started becoming visible when in 1913-14, during a conference held in Delhi, the Chinese, Tibetan, and British envoys (Henry McMahon, assisted by Charles Bell) discussed three major points.

These included that the frontier between China and Tibet should be drawn approximately along the upper waters of the Yangtse; that a frontier should be defined between India and Tibet running along the main range of the Himalayas; and that the Tibetans were to have greater self-determination. Although the agreement was initialled, the Chinese refused to proceed with the full signature. Nonetheless, it was agreed to maintain three Trade Agencies in Tibet—at Gyantse, which lay between the Himalayas and Lhasa; at Yatung, north of the Himalayas; and also at Gartok in western Tibet.

The 12 August 1912 agreement between the Chinese and Tibetan representatives in presence of Gorkha witnesses discussed a “three-point” proposal, which stated that all arms and equipment including field guns and Maxim guns in the possession of the Chinese at Dabshi and Tseling in Lhasa shall be sealed; bullets and gunpowder shall be collected and deposited in the Doring house; and the Chinese officials and soldiers shall leave Tibet within 15 days. As he drew nearer to Lhasa in 1912, the 13th Dalai Lama uncovered that the government of China had broken its pledges of not interfering with Tibet or his position.

Describing the life and times of Tibet, Basil Gould, a British trade agent in Gyantse from 1912-13 narrates in his notes published in November 1949 that the problem of Tibet’s future was whether China would continue to seek to dominate and destroy Tibetan national identity, religion, and its distinct culture. Suffice for me to conclude that Gould’s notes on Tibet’s history have become its present-day destiny, in a fateful paradox.

Dr Monika Chansoria is a Tokyo-based Senior Visiting Fellow at The Japan Institute of International Affairs (JIIA).