After a US lower court’s decision to release Rana on compassionate grounds, GOI moved swiftly and filed for his provisional arrest.

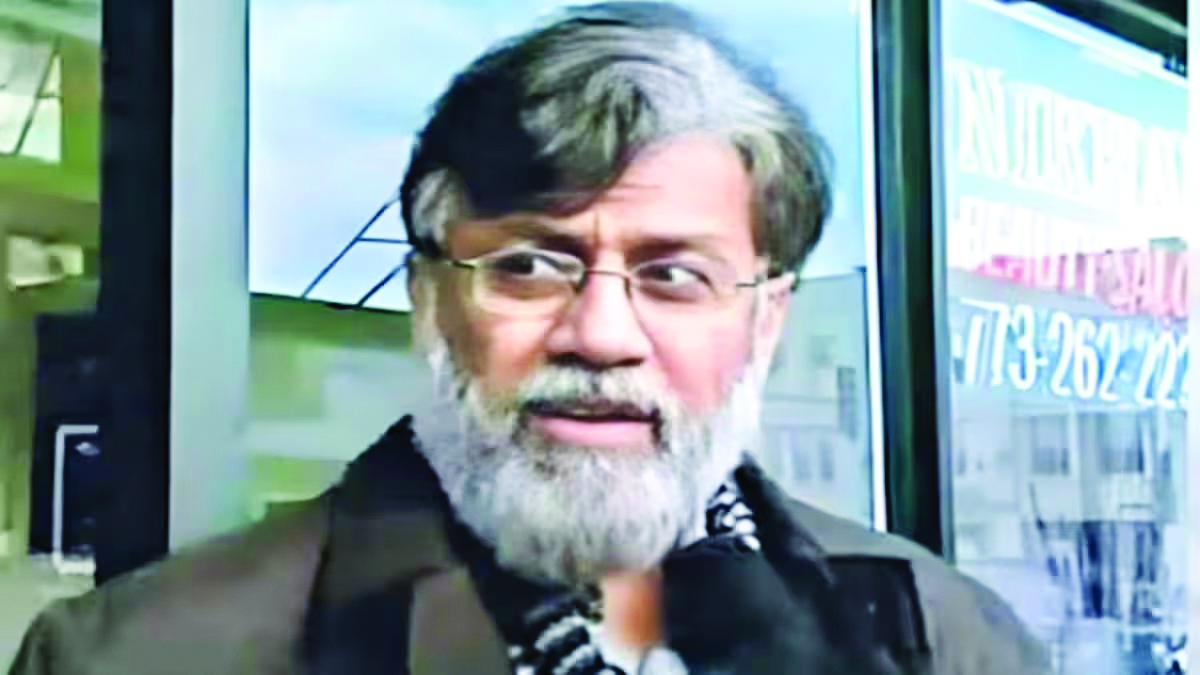

New Delhi: The victims, survivors and the family members of the 166 people who were killed in the horrific November 2008 Mumbai attack by terrorists supported by Pakistan Army officers, are likely to find some closure more than 16 years later with the Government of India successfully being able to secure the extradition of the 64-year-old Tahawwur Hussain Rana, one of the masterminds in the massacre.

On 21 January, Rana’s writ of certiorari was among the 45 such writs that were denied by the Supreme Court of the US while deciding not to review the lower court’s decision to extradite Rana to India.

The situation regarding Rana’s imminent extradition, however, only arose because the Government of India pursued the case with full force, despite a local court having ordered his release on “compassionate grounds” in June 2020.

Following the US lower court’s decision to release Rana on compassionate grounds, the relevant office of Government of India, on directions of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, moved swiftly and immediately filed for his provisional arrest. India’s approach was focused on ensuring that Rana faced justice for his role in the attack, and officials worked through diplomatic and legal channels to challenge his release and secure his extradition. The Modi administration made it clear that the government would pursue the matter vigorously, especially considering the importance of securing justice for the victims and survivors of the attacks.

Court documents accessed by The Sunday Guardian show that among the arguments that Rana raised, albeit unsuccessfully to stop his extradition in the Supreme Court, was facing the “prospect of transfer to a country where his birthplace (Pakistan), his religion (Muslim), and the nature of the charges (terrorist murder of 166 people) mark him for likely abuse—followed, if he survives pretrial incarceration, by a trial with a predictable result and execution by hanging, per India Code of Criminal Procedure”.

Rana also raised the legal defence of “double jeopardy”, with his lawyers arguing that a discrepancy had arisen between the views taken by the lower courts in Rana’s case. Rana raised the question of what the term “offense” meant in the extradition treaty, while referring to the decisions of the lower courts. While a few courts had said that “offense” should refer to the actual actions or conduct a person did (e.g., a specific act of terrorism), the others had stated that “offense” should refer to the elements of the crime (the legal parts or components that define a crime, like planning an attack, being part of a terrorist group, etc.).

Rana’s lawyers had argued that the “conduct-based” approach should be used because it better protects people from being tried twice for the same actions when two countries (like the U.S. and India) are involved. Rana further raised the issue of inconsistency in the application of legal standards while stating that his situation exemplifies the unfairness of the current legal framework, where a person’s fate can depend on where they are incarcerated within the United States. If he had been imprisoned in a different jurisdiction (such as New York, Connecticut, or Vermont), his lawyers said, the legal protections under the Sindona decision could have led to his release much earlier.

In the Sindona v. Grant case of 1974, the US court had ruled that a person cannot be extradited to another country to face prosecution for the same offense they’ve already been tried for in the United States while using a conduct-based interpretation of the term “offense.” Rana’s lawyers asked the court to apply the conduct-based double jeopardy standard, as it would have prevented Rana’s extradition for those charges and limit the prosecution to less severe charges, such as forgery, which would carry far lighter penalties.

Similarly, his lawyers questioned the Executive Branch’s interpretation of the treaty, arguing that the government’s reliance on the Executive’s “technical analysis” of the treaty provision should not be blindly accepted by the courts.

However, all these reasons failed to make an impact on the court, with the US prosecutors giving pointed rebuttal to all the arguments raised by Rana. The US government lawyers said that the “non-bis in idem” clause or “double jeopardy” in the extradition treaty between the United States and India prevents extradition if the individual has already been convicted or acquitted for the same offense in the requested state but it is not applicable in the case as the clause applies to the “same offense” with identical elements, not merely the same conduct or facts.

The prosecutors stated that Rana’s interpretation of clauses in the extradition treaty was incorrect and said that that “offense” refers to a charged crime, not the underlying conduct. Their contention was backed by the technical analysis of the extradition treaty by U.S. agencies (Department of State and Department of Justice), which emphasized the “same-elements” test was correct.

Rana, in his defence, also argued that the U.S. Attorney’s statements during a previous plea agreement involving a different individual (David Coleman Headley, another prime accused in the case) prevents the government from pursuing this extradition. However, the government argued that judicial estoppel did not apply because the plea agreement did not explicitly address the treaty’s provisions in the way Rana claimed. They argued the U.S. attorneys were merely clarifying the terms of Headley’s plea and did not contradict the interpretation of the treaty.

The government lawyers, in counter to the arguments raised by Rana, emphasized that the interpretation of the treaty by the U.S. Executive Branch (State Department and Department of Justice) should be given great weight. The government also pointed out that the case did not present a direct conflict with the Sindona case, as the treaties

The lawyers further stated that not all of the conduct for which India sought extradition was covered by the charges in the U.S. case against Rana. For example, some charges, such as forgery related to fraudulent banking activities in India, were not part of the U.S. prosecution. Therefore, they argued, even if the court ruled on the “non bis in idem” provision, the petitioner might still be subject to extradition for charges not covered by the U.S. verdict.

It is pertinent to mention that after being arrested by the US authorities in October 2009, Rana, in 2013 was convicted of providing material support to terrorism in Denmark and to Lashkar, but the jury stated that deaths had not resulted from his conduct, after which he was sentenced to 168 months in prison, followed by three years of supervised release.

However, on 9 June 2020, the Northern District of Illinois court granted Rana’s motion for compassionate release and ordered him released immediately.

However, on 10 June the US government filed for his provisional arrest in connection to the extradition request made by India under nine charges: (1) conspiracy, (2) waging war against the government of India; (3) conspiring to wage war against the government of India; (4) forgery for the purpose of cheating; (5) using as genuine a forged document or electronic record; (6) murder; (7) committing a terrorist act; (8) conspiring to commit a terrorist act; and (9) membership in a terrorist gang. Following this on 29 September 2020, the U.S. government filed a memorandum in California seeking certification for Rana’s extradition, based on the charges requested by India.