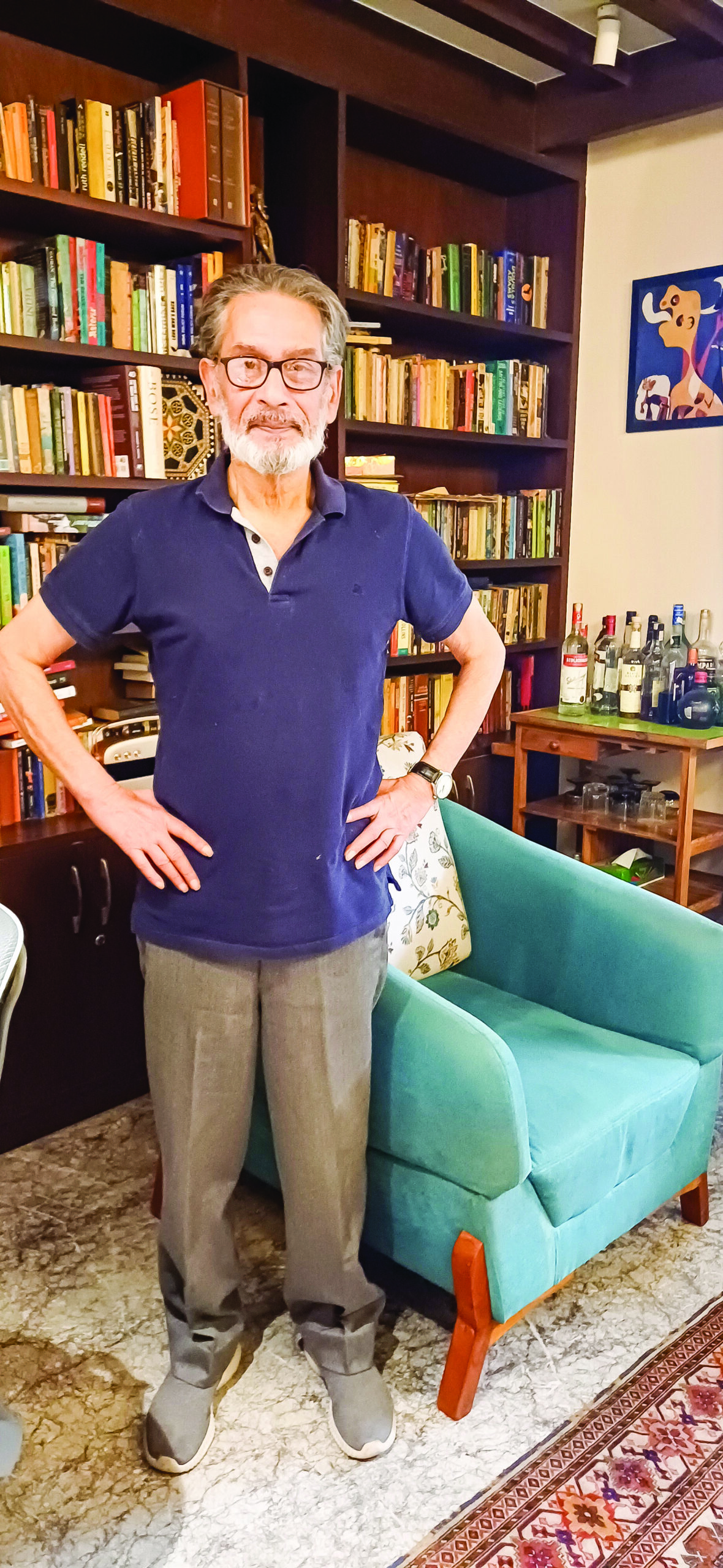

NEW DELHI: At a time when Congress leader Rahul Gandhi has been speaking of wealth survey and redistribution of wealth from his campaign platforms for the Lok Sabha elections, The Sunday Guardian caught up with Pronab Sen, noted economist with PhD in Economics from Johns Hopkins University and former chief statistician of India, to find out how feasible such redistribution is.

Q: There is a storm brewing in the country over the issues of stark wealth inequality and concentration of wealth. Do you support the idea of ascertaining who is in possession of the wealth of the country and redistributing the same?

A: Well, up to a point. This makes a lot more sense when you are talking about poverty. You want to get people up to a minimum. But purely distribution as a means of wanting to get inequality out, is more problematic. The real answer to that is not a tax and transfer. That’s not the real solution. The real solution is what your development strategy is. What is your growth strategy? Are you creating conditions whereby those segments of the economy which give rise to a more equal income? Are they being encouraged on that? That is the appropriate question to address.

Q: There have been several reforms in the Modi 2.0 which government says have taken the economy to big heights and put money in hands of the people. But there is a perception in the middle class that wealth disparity has exacerbated.

A: Not really. The middle class has not thought like that, particularly the upper middle class. The middle class hasn’t done badly. The real issue is the lower middle class, which is really politically the most dynamic and volatile. In their case, a lot of their well-being really depends upon the MSMEs. And there is really no strategy, no real diagnosis about the nature of their problems. And, therefore, the strategies that have been employed, like working capital guarantees and things like that, they only address it at the margin. It doesn’t do anything substantial.

There used to be a time, if you go back to the 1960s, where it was said that the middle class was gaining at everybody else’s expense. Political systems do have alignment with particular industrialists, do create a whole generation of industrialists who are beholden to them. So, this is a game that’s constantly being played. they keep pointing fingers at each other. Both sides play the game.

Q: Since when has India been witnessing wealth disparity?

A: In fact until the 1991 reforms, India’s income distribution—wealth distribution is a little more tricky—was relatively better than most countries. This is by and large true of developing countries. After 1991 after the reforms unravelled and when the private sector started booming, income inequality starts increasing. This has been continuously increasing since then. It has now been in process for 30 years and now our income inequality is very high. The data that we have, is now capturing inequality less than it used to and the reason for it is that the surveys that we carry out don’t cover the rich very well. In fact, the rich just refused to participate and because of that, if there is growing disparity, we are capturing the lower end very well, probably capturing up to about 90% of the population. The last 10%, the coverage is extremely low.

In the pre-reform era, with regard to poverty alleviation—Garibi Hatao—this has to be seen from the prism of two issues. One is disparity which is inequality. The other is poverty—it is about income, spending. The two have distances, we need to be very careful. Removing poverty really means you’re trying to improve their incomes and spending. Now, that can happen whether your income distribution improves or even gets worse. So if the country is growing and the lower tail is also growing, but the higher tail is growing faster, then poverty could go down, but income disparities could continue. When you think about it that way, we should treat them as separate measures to be used for different purposes. Poverty is really a “less basic means” issue.

Q: The 1991 reforms were supposed to liberate the economy, create opportunities for people and economic betterment. Did the reforms help mitigate the wealth disparity?

A: The reason for sharper inequalities, if you think about the economic reforms, were about unshackling entrepreneurs who were controlled under the licence regime. So the 1991 reforms were essentially about getting rid of those licences. A few of those businessmen grow very well, they are really good entrepreneurs and they take off. A few others fall by the wayside. Now, the whole idea was that this would lead to greater entrepreneurship and then, through a trickle-down process it would benefit people lower and lower.

That has happened. It’s not that benefits have not percolated down. From 1991, poverty has come down steadily and sharply. But inequality has gone up. So, if you think about an average growth rate—let us say of 6-6.5%. In this period you probably have a situation where, at the bottom, you are getting maybe 1% or 2% increase a year. And at the top, you are probably getting 7%, 8%, 10%. So, the gap is just increasing.

The decade of the 1990s was essentially start of the process of unshackling the entrepreneurs. Now, that takes a little bit of time. You really saw the fruits of that happening during the 2000s when the growth rate went up very sharp—you start the process and then it builds up momentum and takes off. Now, at that period, in the 2000s, we had an interesting situation, which is that when you look at growth rates—both corporates and the MSME sector were growing very strongly. In 2009, you get the global financial crisis. At that point in time corporates slowed down dramatically. Because they were much more exposed to global factors. The MSMEs were not. They continued to grow. So, in fact, income distribution improved.

Q: What about the decade of 2000? How was wealth distribution changing?

A: In 2014, things start turning around. The corporates start picking up again. Then comes 2016—the demonetization. There, the effect was exactly the reverse. The MSMEs, who were very cash dependent, slowed down and the corporates took off. The initiatives which were taken by the government to address the plight of MSMEs and the stimulus happened when government actually stepped in, not after demonetization, but during the pandemic. And there, the first step was really taken by the Reserve Bank. And what they did was extremely important. They put a moratorium on repayment of bank loans. Now, that was important and it saved a lot of MSMEs. But not all. What happened is, MSMEs which survived, did well.

The point is that we have lost a lot of MSMEs along the way. We don’t have hard estimates about the numbers but vague estimates that we have, suggest about 15-20 per cent of the MSMEs just closed and never come back. Nothing has been done really to create new SMEs. That is not happening. The reason is that bank loans are essentially being made for working capital. Now, working capital is relevant only to a unit that is actually working. If you are going to start up, you need actually risk capital.

Q: Coming to the present, do you agree with Congress that India needs a survey to find out who owns how much wealth and distribute it?

A: The whole problem is that they haven’t done a census. This would have to be almost based on a census. In fact at the moment our information, that we use, is on the basis of sample surveys. These are small samples—1.4-1.5 lakh households. Here they are talking of a full census. They want to identify specific households. The only time you did that was in 2012 when we did the socio-economic and caste census. We have not repeated it. Now the entire anti-poverty programmes that we have had since, the beneficiaries are based on the 2012 data and a lot has changed since. So in a sense if Mr Gandhi is talking about repeating that, there is a lot of sense because we are giving benefits to people on the basis of data which is 12 years old.

Q: What about the inheritance tax? Is India ready for it?

A: The whole idea of an inheritance tax is that while you have a right to the wealth you have, you have no intrinsic right to the wealth that you have inherited. That is an accident of birth. What it allows you to do is, going by the theory, that it pushes up your tax collections which in turn allows you to bring down tax rates on current revenues. Should it be done in India? Well it is very difficult to do it in India. We found that out. That is why it got abolished. What it did lead to, at the time, was firstly there was a huge amount of corruption because you had to do evaluation. The second thing was that you got very little out of it in terms of money. The point is that the costs are high. Both the collection costs are high and the corruption costs are high. And the benefits have not been substantial. So unless you can change these things, measure these things properly without this kind of human intervention, it is difficult.