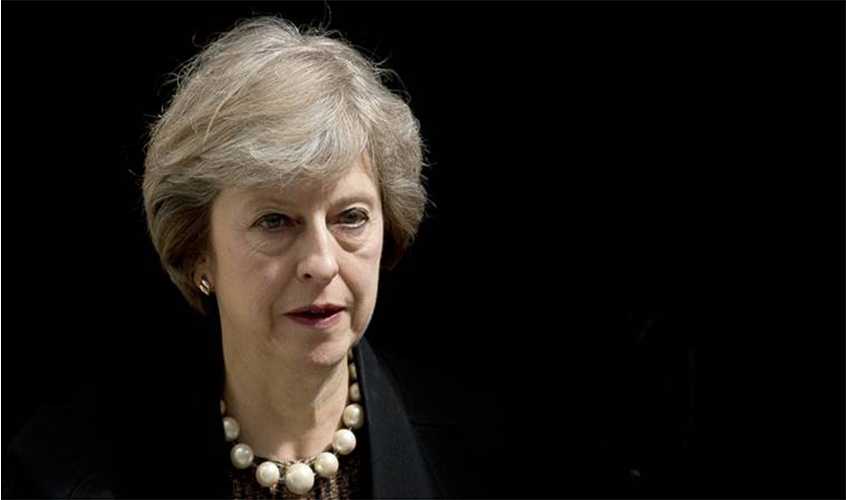

British Prime Minister Theresa May gave her Brexit speech in Florence. The speech was heralded to be enlightening about UK’s future relations with Europe.

Florence is a spectacularly scenic venue, yet the PM chose to speak in front of an uninspiring white background, which could have been in any boardroom anywhere. A notable contrast in stage management to Emanuel Macron speaking in Versailles and in front of the Acropolis recently.

The Prime Minister’s tone inched towards a marginally better engagement with Brussels, but the consensus, on both sides of the Channel, was that the content was unsubstantial and disappointing. May referred many times to her Lancaster House speech in January 2017 which gave the impression that negotiations had barely moved on. The PM uses the singular form of the first person when delivering a speech. This gives the impression the ideas are hers and that her government is not like minded or unified.

The transition period that semi-satisfied business and Remainer interests has morphed into a proposed implementation period of about two years after March 2019, to allow for preparation to adapt to the new set of rules. During this two years UK proposes to continue to enjoy the single market and yet not to commence trade deals; some question if this would this leave the UK Trade Minister’s team at a loose end. This also suggested that during the next four years the UK would honour its share

The eventual trade deal was defined in reverse, instead of defining what shape it might take, it was defined as what it would not be. The PM offered Europe a new relationship on security, a treaty that encompasses security, law enforcement and criminal justice co-operation; British superior expertise in this area should be welcomed in Europe and May explained to Europe that UK had no intentions of undercutting regulatory standards.

The line in the speech that rang true for many was “the United Kingdom has never totally felt at home being in the European Union”. The lack of support for May’s speech was evident in the resulting conservative press and the paucity of endorsing tweets from MPs. Following May’s speech, Moody’s Investors Service downgraded the UK’s long-term issuer rating to Aa2 from Aa1 and changed the outlook to stable from negative and UK’s senior unsecured bond rating was downgraded to Aa2 from Aa1. This is the lowest credit rating ever for UK: “Moody’s is no longer confident that the UK government will be able to secure a replacement free trade agreement with the EU which substantially mitigates the negative economic impact of Brexit.” If the government had been fully committed to Brexit and appropriately prepared, surely the two years between declaring Article 50 and March 2019 could have been the transition/implementation period. Since May’s speech @Number10gov have been busy communicating in German by tweet the EU favourable aspects of May’s speech. These tweets are only visible in the EU, no doubt compensating for the lack of European political representatives in Florence.

May offered an olive tree to Brussels and an anti-climax to Brexiteers. Michel Barnier, EU’s Chief Brexit negotiator, acknowledged May’s “constructive spirit” and Guy Verhofstadt, EU Parliament Member, was quick to reiterate that UK could not cherry pick an exit route; in both their responses they indicated that the UK and Europe’s “deep and special partnership” that May allegedly desires is a long way off and they still intend to make it difficult to achieve.