Born in humble circumstances in February 1954, Erdogan was active in Islamic circles for two decades after graduation before joining the pro-Islamist Welfare Party and becoming Istanbul’s mayor in 1994.

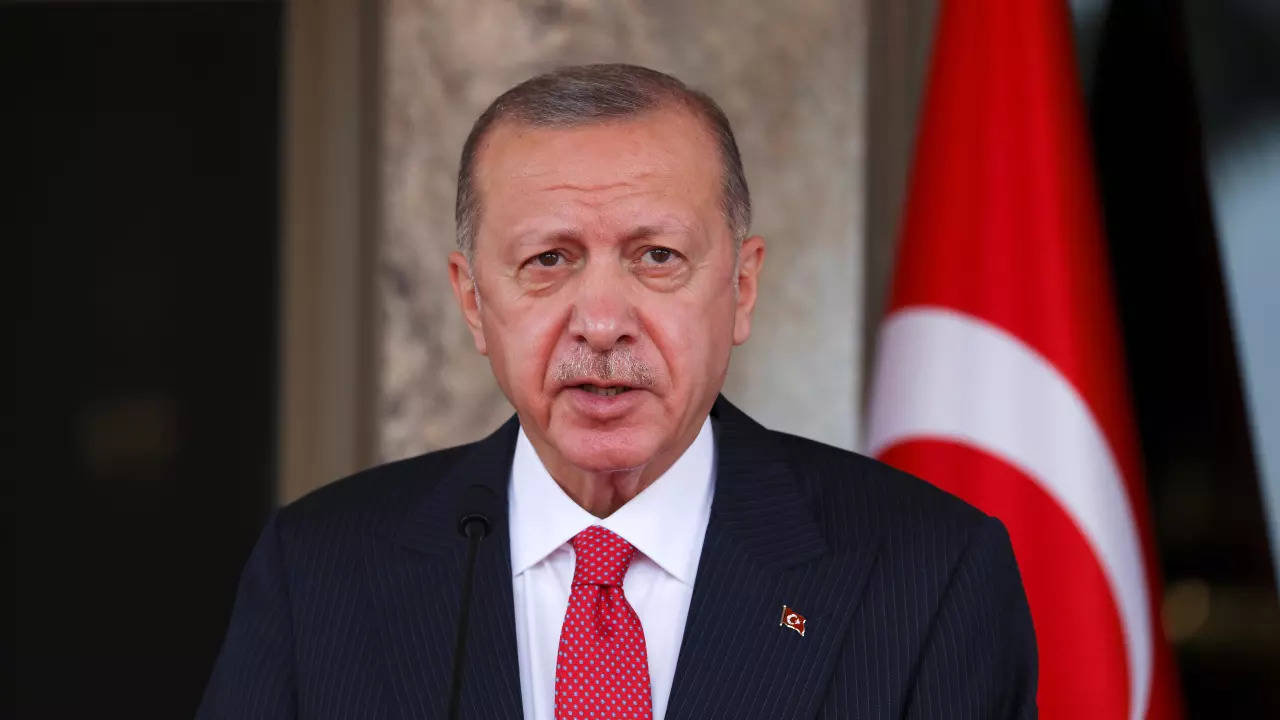

Today, Recep Tayyip Erdogan will face the toughest political challenge of his presidency when voters make their choice. The result of today’s election will not only determine who leads this significant country of 85 million but also how it is governed, where its economy is headed, and the shape of its foreign policy. The stakes couldn’t be higher for Turkey. It’s a sign of the country’s regional power and its weight in the wider international system that policymakers in western capitals, Moscow, the Middle East, and beyond are watching with extreme interest.

Many consider Erdogan to be Turkey’s most powerful leader since Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, who founded the modern republic a century ago, putting the country on a largely secular political path that broke with its Ottoman past. Kemal modernised Turkey by separating the laws of Islam from the laws of the nation, abolishing religious courts, creating a new legal system based on European law, granting women the right to vote and hold public office, and launching government-funded programs to spur economic growth and industrialise the country.

This path continued until the arrival of Erdogan in 2003. He and his Islamist-based AK Party have shifted Turkey away from Ataturk’s blueprint and now stand accused of returning the country to an imperious, neo-Islamist style of rule, evoking the reign of the sultans. By centralising power around an executive presidency, which determines policy on the economy, security, domestic and international affairs, Erdogan has exposed himself to criticism for muzzling dissent, eroding human rights, and bringing the judicial system under the control of his presidency.

Born in humble circumstances in February 1954, Erdogan was active in Islamic circles for two decades after graduation before joining the pro-Islamist Welfare Party and becoming Istanbul’s mayor in 1994. His term came to an end when he was convicted of inciting racial hatred, and after four months in jail, he returned to politics. Finding his party had been banned for violating the strict secular principles of the modern Turkish state, Erdogan founded a new Islamist-rooted party, the Justice and Development Party – AKP. From 2003, he spent three terms as prime minister, presiding over a period of steady economic growth and winning praise internationally as a reformer. The country’s middle class expanded, and millions were taken out of poverty as he prioritised giant infrastructure projects to modernise Turkey.

However, critics repeatedly warned that he was becoming increasingly autocratic. Some accused him of hollowing out, bending, and fashioning political institutions to ensure his grip on power. By controlling 90 percent of Turkey’s once boisterous, if not always responsible, media, Erdogan can ensure that it always echoes and expands the government line. The Judiciary, once a stronghold of the secular nationalist establishment, is now the preserve of AKP’s supporters. Purges have now become a regular feature of Turkish politics, and many believe that today’s election is taking place in an increasingly undemocratic environment.

So, how are the people likely to vote today?

On the surface, Turkey’s Islamist leader is looking more vulnerable than ever before. In the run-up to the polls, Turks have had much to complain about and grieve over – from the state’s slow response to February’s earthquakes to an economy in ruins. The official toll from the worst natural disaster in Turkish modern history is more than 50,000, although many believe that the real figure is much higher and the government has stopped counting. The earthquakes exposed structural faults in Erdogan’s long rule. He permitted more than one hundred amendments to public-procurement laws, and granted the award of construction contracts to allies, especially to a group of companies that became known as the ‘Gang of Five’. He also presided over repeated amnesties for illegal construction, an error of epic proportions as hundreds of tower blocks inevitably fell like matchboxes during the earthquake.

As much as Turks are angry about the pitiful government response to the earthquakes, they are equally angry at the state of Turkey’s economy. In the first 10 years of AKP rule, the economic policies were orthodox, and the economy grew swiftly, averaging 5.8 percent between 2002 and 2021. When economies grow rapidly, interest rate rises are often used by central banks to cool down the economy by increasing the cost of borrowing. But not in Turkey. Instead of increasing rates to support the Turkish Lira, Erdogan, who considers himself an economic genius and who controls Turkey’s Central Bank, insisted on slashing rates to rock-bottom levels.

The inevitable result was a plunge in the value of the Turkish Lira and soaring inflation, reaching a 25-year high of 90 percent last October. Confidence in the economy collapsed, and foreign and local investors pulled their money out of Turkey, compounding the problem. The country’s foreign reserves have been seriously depleted by Erdogan’s unorthodox economic policies. On Wednesday, it was announced that Turkey had deferred payment to Russia of a $600 million natural gas bill until 2024. It is understood that under the terms of the agreement, up to $4 billion in Turkish energy payments to Russia will be postponed. Turkey’s growing relations with Russia have raised concerns in the West that the country was straying from its NATO ties.

In a further sign of panic in December, Erdogan raised the monthly minimum wage for workers by 55 percent to the equivalent of $454, from $312 a year ago, and on Tuesday, the government announced that it would be increasing the public sector wages by 45 percent, taking the lowest public worker’s wage to TL 15,000 ($768) per month. The fact that the announcement was made just five days before the election was, of course, just a coincidence!

On the face of things, today’s elections promise to be closely fought. At the time of writing, the opinion polls indicate that Kemal Kilicdaroglu, the 74-year-old leader of the six-party opposition bloc, will get 49 percent of the vote in the first round, just short of the 50 percent needed for a clear victory. However, the surprise announcement on Thursday of opposition candidate Muharrem Ince that he was pulling out of the contest could push Kilicdaroglu over the line, thus avoiding a second round. If neither candidate gets 50 percent, the contest goes to a second round, to be held on 28 May.

But if he were to lose the presidential race, would Erdogan accept defeat? Or would he find some way of overturning the result through judicial intervention, a vote recount or some other means? The scene is already being set for the latter. Erdogan said recently that a Kilicdaroglu victory could happen only with the support of ‘Qandil’, a reference to the outlawed Kurdistan Workers Party, or PKK, which Turkey recognises as a terrorist organisation based in Iraq’s Qandil Mountains. Turkey’s Interior Minister, Suleyman Soylu, last week compared today’s elections to the coup attempt of 15 June 2016, creating the extraordinary scenario of the man in charge of the security of the ballots presenting the election as a coup attempt before anyone has even voted. Another heavyweight of Erdogan’s party, Binali Yildirim, equated the elections to Turkey’s war of independence after WW1, and yet another AKP official, Nurettin Canikli, claimed that Turkey would cease to exist as a nation if the opposition were to win the election. All of these statements, which would only have been made with the approval of Erdogan, are a clear threat to the nation’s will. By declaring success at today’s polls as a matter of life or death for the country, Erdogan is turning the event into something more than just an election. The not-so-subtle hint is that he won’t be giving up power even if he loses.

So, it is indeed a crunch day for Turkey and its president, a moment in time that could be one of the most critical in the history of modern Turkey.