One of the biggest questions roiling Pacific countries is “will the United States militarily defend its Asia-Pacific allies in a time of conflict?” Much of the strategic architecture of the region is predicated on a “yes”. That’s why there are US bases in Japan, close American military cooperation with the Philippines, rotating Marines in Australia, and more. Much more.

China has been working hard to undermine those relationships. It declared an Air Defence Identification Zone that covers areas claimed by Japan, in part to see what the US would do (officially, the US didn’t do much). Beijing is actively courting regional leaders like President Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines (though Duterte himself seems much more willing to work with President-Elect Donald Trump than he was with President Barack Obama). Australia allowed a Chinese company to lease a port right next where the Marines are stationed in Darwin. And more. Much more.

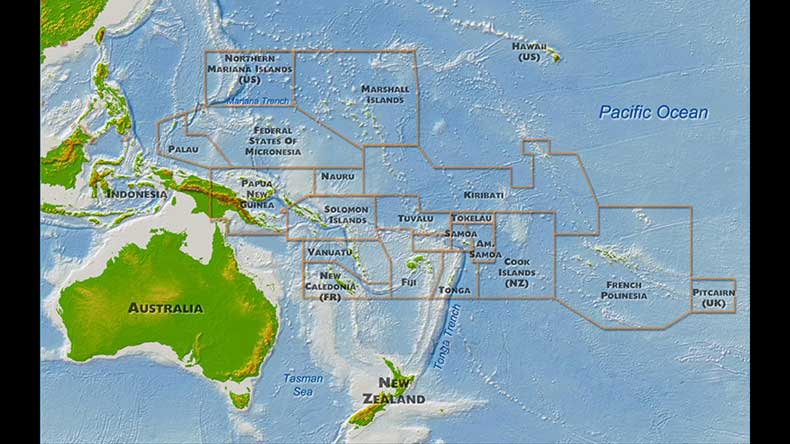

One zone where this geostrategic chess game is moving at a dizzying pace is Oceania. Oceania is roughly the zone between Hawaii, New Zealand and Japan. Made up of over a dozen independent countries, and covering close to 1/6th of the planet’s surface, it is still littered with the rusting carcasses of World War II era Japanese and American planes and boats left over from the last time it was at the front line of a conflict between Asia and America.

From a defence, intelligence and economic perspective, Western presence in the area is mostly covered by Australia and New Zealand. However, both have a track record of regularly using their influence in the region to advance their own narrow interests, sometimes to the detriment of regional (and even their own) security.

For example, when the country of Tonga wanted to introduce more renewable energy into its grid in order to lower rates, Wellington actively used its aid and influence to try to ensure a key solar power procurement contract went to a New Zealand company, even though the company had little experience operating in a tropical region. The end result was that the Japanese had to step in to complete the New Zealand-built solar plant and there was no reduction in cost to the consumer, in some cases costs actually increased.

This sort of ill-conceived, heavy-handed interference has weakened the Western position in the region and, in the medium and long term, is damaging to Australia and New Zealand themselves.

It has also left the door wide open for China. China’s footprint in the region has expanded very rapidly, on multiple fronts. In Samoa there are plans for China to build what will be the largest wharf in Australasia. In Fiji, there has been extensive military cooperation. In Tonga, newly arrived Chinese have taken over around 90% of the retails sector in less than a decade. And the list goes on.

The response from Australia and New Zealand has been conflicted. While some in the political and strategic communities are clearly concerned, others seem resigned.

At a macro level, former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd said in 2009 that the US would not protect Australia in a time of crises. More recently, former Australian Prime Minister Paul Keating said that Australian foreign policy has been “tagging along” behind the US, and that Canberra should “cut the tag”.

At a micro level, grasp of the speed and degree of change is sometimes dangerously incomplete. Recently, in Tonga, a Chinese shopkeeper was attacked in her sleep and nearly killed. A young Tongan man was arrested. The New Zealand press used the incident to promote the narrative that Tonga, and Tongans, are violent and increasingly unstable, justifying more “impartial” New Zealand oversight.

In response to its own narrative, New Zealand sent an ethnic Chinese New Zealand policeman to Tonga to embed with the Tongan police in order to “help protect” the ethnic Chinese in Tonga. In reality, however, the Tongan attacker was hired by a Chinese businessman to attack a rival. This was all about crime within the newly arrived Chinese community, not about Tonga. The New Zealand response only exacerbated the situation.

Similarly, New Zealand is pushing for the commercialisation of customary lands in various countries in Oceania. The expectation in Wellington is this will benefit New Zealand business in the region. What is more likely, as Samoan academic Dr Iati Iati has shown, is that the locals will be disposed and may become desperate, meanwhile the land itself is more likely to end up with Chinese investors. Again a lose-lose situation.

It is in this context that, last week, the University of French Polynesia convened a high level conference called “Coveted Oceania”. France has vast ocean territories in the Pacific, based primarily on its two possessions, New Caledonia and French Polynesia. In the last year, the French profile in the area has grown rapidly. In April, in a deal worth close to $40 billion, France won the contract to build 12 submarines for Australia (New Caledonia and Australia share a maritime border). And just a few months ago, New Caledonia and French Polynesia joined the Pacific Island Forum. On the sidelines of the “Coveted” conference there was active engagement with Australian academics with the goal of expanding collaborations. France is suddenly much more visible in Oceania.

Oceania is changing fast. And India will be affected. As the “Indo-Pacific” century rolls on, the strategic spheres of the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean will increasingly overlap. The election of Donald Trump is only likely to increase US ties with India, and give India latitude for its “act East” policy. Narendra Modi and Japan’s Shinzo Abe, not only get along with each other, they also seem to be among Trump’s favourite foreign leaders. And all three are cautious about China.

Abe wrote about a democratic Indo-Pacific security diamond, with the Japan, India, the US (Hawaii), and Australia at the points. However, Japan was bitterly disappointed that Canberra chose to buy French submarines rather than Japanese ones and, at the same time, the Australian strategic community seems to be conflicted and is sending out mixed messages. While some are passionately devoted to the “diamond” (or similar), others are not so sure the US will come to its aid in a crisis and are proposing hedging their bets, perhaps with countries that are not democracies. The potential resurrection of France in the region adds a new element.

In an Oceania context, it’s not clear if the “diamond” (Japan, India, US, Australia) will solidify or if it will become more of a triangle (Japan, US, India), or perhaps even expand in some areas into a pentagon (Japan, India, US, Australia, France).

Whatever happens, there is no question India will become more involved in Oceania. There are plans for an Indian space research station in Fiji, growing economic ties with Vanuatu, and a whole slate of bilateral proposals crafted since Prime Minister Modi visited Fiji in 2014.

So will the US defend its Asia-Pacific allies in a time of conflict? Hopefully, ties between democratic partners will strengthen and it won’t have to. The chances of that are greatly improved if the countries of Oceania are given the space to develop stable societies and economies instead of being used by regional powers as outlets for short-term narrow economic interests that end up giving long-term advantage to China. If Canberra and Wellington want to feel more secure about their relationships with Washington, Tokyo, Delhi, and Paris, they might want to rethink their relationships with Nuku’alofa, Apia, Honiara and Port Moresby.

Cleo Paskal is The Sunday Guardian’s North America Special Correspondent.