BENGALURU: To use the Hanuman Chalisa as a vehicle for an ideological outburst makes Seth little different from those he accuses of ‘intolerance’ and ‘chauvinism’.

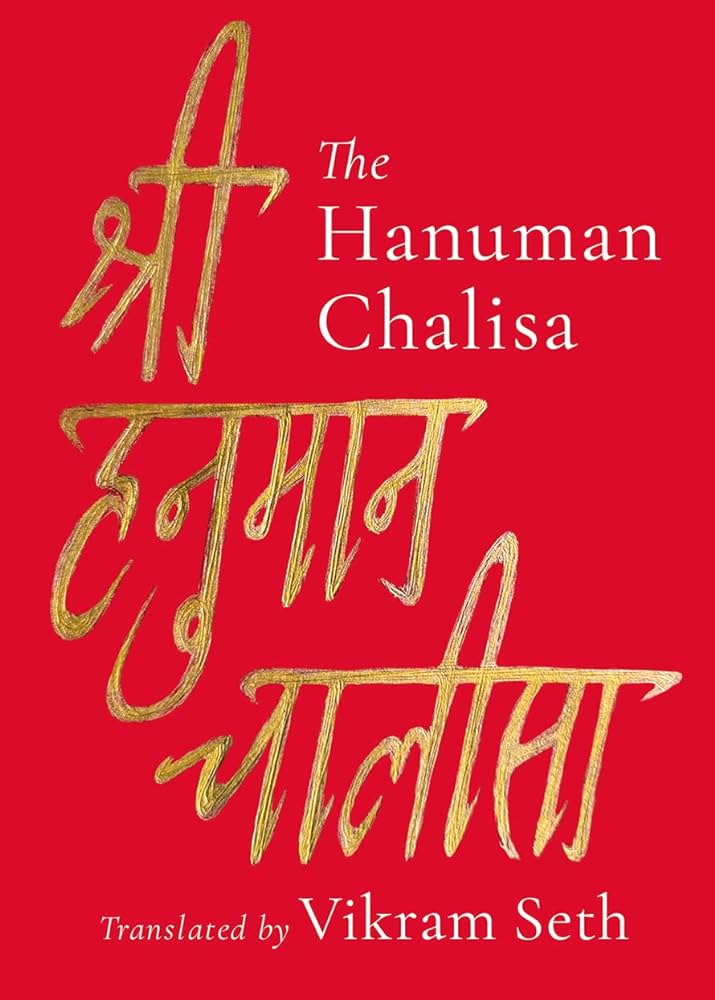

When Vikram Seth, praised as the “best writer of his generation” by the Times, and author of “A Suitable Boy”, called “the most prodigious work of the latter half of [the twentieth] century” by the Times, pens a translation of Hanuman Chalisa, one of the most famous and revered works of 16th century CE Hindu poet, Goswami Tulsidas, one cannot but get a copy.

Apart from penning Ramcharitmanas, a retelling of the story of Lord Rama, Tulsidas’ other famous work is Hanuman Chalisa, a collection of 40 verses in praise of Hanuman. Hanuman is considered both an avatar of Lord Shiva as well as the son of the wind God, Vayu. He was also a great devotee of Lord Rama. The Hanuman Chalisa consists of two invocatory dohas (couplets) in the beginning, followed by 40 chaupais (quatrains), and one concluding doha.

The Hanuman Chalisa is written in Avadhi, a language most native speakers of Hindi will be able to follow with ease, and even non-native Hindi speakers will pick up with minimal effort. Across thousands of temples and millions of homes in India, and especially in northern India, the Hanuman Chalisa is recited every day by millions, and is as common and ubiquitous as Venktesa Suprabhatam is in southern India.

One of the distinguishing features of Vikram Seth’s translation is the use of both rhythm and rhyme, instead of a free-verse translation. His formidable skills as a poet come to the fore, and some of the translated quatrains are almost sublime, like the 5th and 6th chaupais. The use of rhyming words also means, however, that in some instances the translation will fall short for want of that perfect word that fulfils the demands of both fidelity and meter. In other cases, some context and meaning are inevitably lost in translation. There are some non-translatable words that necessarily lose both meaning and subtlety when translated into English. Dharma is one such word, but there are others.

In the 9th chaupai, for instance, sookshma and bikaTa are translated as “tiny” and “awesome”. “Subtle” and “formidable” would have been more correct. In the 10th chaupai, Ramachandra ke kaaja sa(n)waare is translated as “Act after act, Lord Ram obeying”, which is inapt, even by any stretch of poetic licence. In the 18th chaupai, juga sahasra jojana para bhaanoo has subtext that is utterly lost in the anodyne “Far in the distance”. The use of juga, sahasra, and jojana—all three denoting numbers—not only convey a sense of a great distance, but when multiplied together (a juga is 12,000; sahasra is 1,000; and a yojana is approximately 8 miles), give a number of 152 million kilometers, remarkably close to the actual distance between the earth and sun. Coincidence, some may argue, but this is a fascinating selection of words in the chaupai. “Far in the distance” is far, far away from the chaupai.

In the 36th chaupai, translating Jaya as “Hail” is an arguably contentious selection, but perhaps allowed as artistic liberty. However, the translation of the 37th chaupai, sankaTa kaTai miTai saba peeraa; jo sumirai hanumata balabeera, as “For those who seek him through meditation, Grief gives relief, pain liberation” is inexact. It is not pain that gives liberation, as Vikram Seth translates, but it is through the act of remembering (sumirai) Hanuman (balabeera) that liberates (miTai) one from pain (peeraa). “Grief gives way to relief” would have conveyed the meaning better—a victim of the demands of rhythm?

The book has no notes, no history of the poem, nor a discussion of its structure—this is deliberate, Seth writes in the Introduction, to avoid “encumbering” the translation with “apparatus”. The last few paragraphs of the Introduction, however, have little bearing or relevance on the translation except to serve as an outlet for propaganda. To use the Hanuman Chalisa as a vehicle for an ideological outburst makes him, ironically so, little different from those he accuses of “intolerance” and “chauvinism”.

When writing about, translating, or otherwise adapting Hindu texts in creative works, what distinguishes one text from the other is the amount of shraddha (loosely translated as adoration, devotion). When that is missing, the motives are, at best commercial; at worst, mala fide. Without taking away from the beauty of a handful of the translated quatrains, the book is notable more for being an exercise in ego aggrandizement and less a “labour of love”.

Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal.