With the new Netflix documentary Rolling Thunder Revue, Martin Scorsese and Bob Dylan have come together once again to bring to life the howling ’70s of American history. In 2005, Scorsese had made another Dylan-centric documentary, No Direction Home. But this one explores new territory, between past and present, and between fact and fiction.

The new film has a splash of old interviews and a sprinkling of Dylan looking back on his golden years. From the very first second, the screen comes to life and the audience is transported to a bygone era. Dylan declares cheekily at the beginning, “I don’t remember anything about the Revue”, referring to the 1975 world tour called Rolling Thunder Revue, on which Scorsese’s film is based.

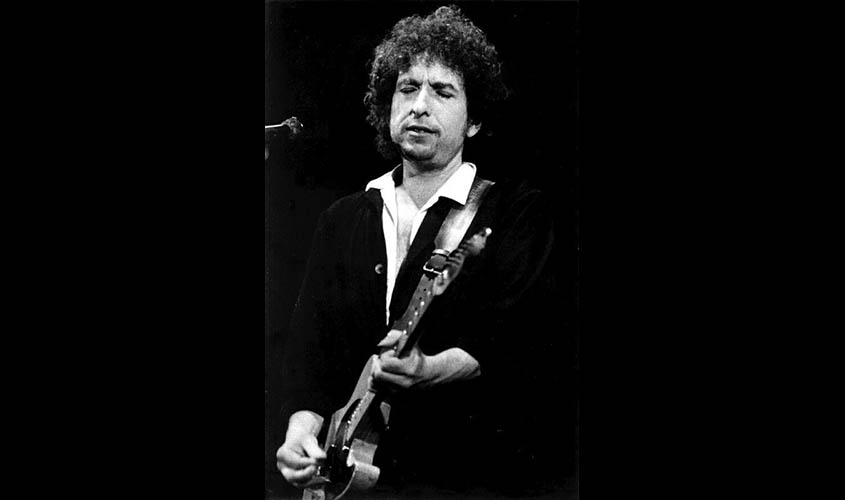

The music starts drifting in, and with “Mr. Tambourine Man” playing in the background we catch our first glimpse of Dylan, in full makeup regalia strumming a guitar onstage in 1975.

This image recurs throughout the documentary, which features a wide variety of Dylan’s famous songs from that era. But in spite of the title, Rolling Thunder Revue is not simply a Bob Dylan story. It is also a tale of the cultural efflorescence that America witnessed in the ’70s. A number of perspectives play around the figure of Bob Dylan: Joan Baez, Joni Mitchell, Rambling’ Jack Elliott, Roger McGuinn, Scarlet Rivera and Allen Ginsberg.

Scorsese is not unfamiliar with musical stories. He has made documentaries like The Last Waltz, Shine a Light and Living in the Material World—not to mention No Direction Home—in the past, and has worked with some of the best musicians of his generation.

The crux moment of Rolling Thunder Revue comes towards the end, when Dylan tells us, with a teasing smile, that “nothing [remains of the tour], not one single thing. Ashes.” With only a handful of people from the Revue tour alive today, Dylan’s statement almost rings true. In fact, it would have been entirely true had it not been for the existence of The Rolling Thunder Revue: The 1975 Live Recordings, a 14-CD box set whose sounds accompany the Netflix movie.

The difference between truth and falsehoods has a greater bearing on Scorsese’s film. The recent reviews have centred on the discrepancies between what is portrayed and what actually happened, with many Western publications accusing Scorsese of peddling fake stories and interviewing fictional characters.

For instance, the supposed videographer for Scorsese’s film is a man named Van Dorp, who, many critics have claimed, is actually the performance artist Martin von Haselberg. The actress Sharon Stone claims in the film that she met with Dylan during the Revue tour in Pennsylvania, where in truth the tour never went to Pennsylvania. Congressman Jack Tanner in the film is also not a really Tanner—it is a role played by actor Michael Murphy, who also appeared in M*A*S*H. Jim Gianopulos, featured as a concert promoter in the documentary, is actually the CEO of Paramount Pictures.

Both Netflix and Scorsese have not been shy to admit that the documentary is “part concert film, part fever dream” and an “alchemic mix of fact and fantasy”.

Besides, this kind of poetic license in no way hampers the experience of watching a film on a musical tour that most people, including Dylan, have all but forgotten.

The documentary, or better yet the pseudo-documentary, shines best when it captures intimate encounters—between Dylan and his fans; between Dylan and Joan Baez, discussing their love lives, with Baez saying, “I thought I had married the man that I loved.” In another instance, a driver recalls going for one of the Revue shows, which changed his perspective on rock ’n’ roll. He felt that the audience and the performers were “batteries charging one another”.

It is important to note that Ginsberg, the greatest American poet of that time, accompanied Dylan’s troupe, wishing to plunge into the world of songwriting. Dylan calls him “his own kind of king” who “wanted to play music”. Ginsberg added another dimension to the Revue tour, and usually entertained the audience with a piece of poetry before every show.

Scorsese’s film explores other big themes as well. For example, the bicentennial anniversary of the birth of America, and the reinvention of that country through music. The aftermath of the Vietnam War, and how Dylan’s music in those days acted as a source of comfort for young souls.

Dylan’s songs often forayed into political territories. A journalist with Rolling Stone magazine, Larry Sloman, who accompanied Dylan’s troupe and is featured in this film, tells us that the title of the tour, Rolling Thunder, was inspired by the name of an Indian chief and was also, as they came to learn later on, Richard Nixon’s codename for the bombing of Cambodia.

At the end of this documentary, Dylan declares, “No, it [the Revue tour] wasn’t a success if you measure success in terms of profit. It was a sense of adventure. So in many ways, yes it was very successful.”

Scorsese’s film, too, is a success in many ways. It deftly moves between fact and fiction, reminding us of what Dylan mischievously warns us about at the very start of the film—to not trust anyone without a mask. Hence, we must take this documentary on its face value, and not worry too much about whether what we have before us is a face or a mask.