“If you intend to have a long career in show business,” Elvis Costello wrote in “Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink,” his terrific memoir, “it is necessary to drive people away from time to time, so they can remember why they miss you.”

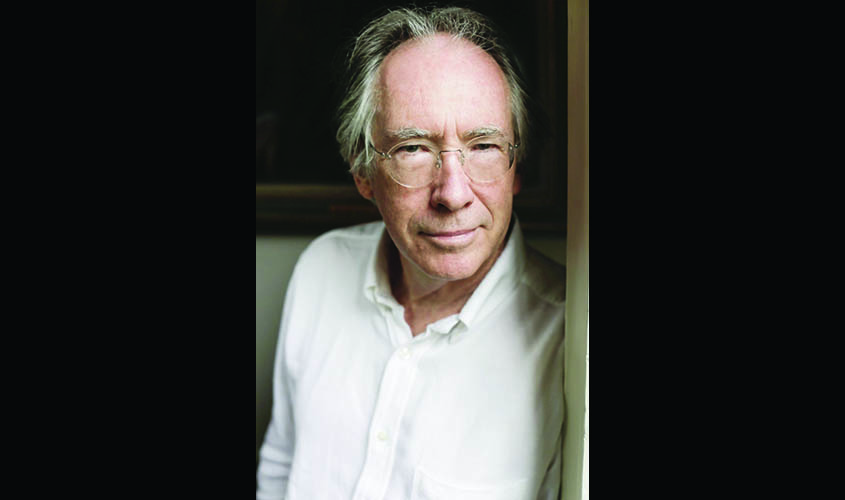

It’s been difficult to miss Ian McEwan. “The Cockroach,” his satirical new Brexit novella, is his second book this year and his third in three years. “The Cockroach” is so toothless and wan that it may drive his readers away in long apocalyptic caravans. The young McEwan, the author of blacker-than-black little novels, the man who acquired the nickname “Ian Macabre,” would rather have gnawed off his own fingers than written it. At dark political and social moments, we need better, rougher magic than this.

By Ian McEwan

99 pages.

Price: Rs 549

“The Cockroach” proposes a reverse-Kafka: A cockroach wakes in the body of a man. This man, it happens, is the prime minister of the United Kingdom. His Cabinet: They’re mostly cockroaches in human form, too. So, probably, is the president of the United States, a Twitter-addled vulgarian. (Wasn’t this all in an episode of “Black Mirror”?) These insects are here to sow human discord, under the guise of patriotism and phrases like “blood and soil” and the notion of making things great again, to ensure their own survival in the resulting rubble.

McEwan is hardly a dummy; he derives more than a few witty-ish moments from his premise. The best arrive early. Our antihero begins to understand that “by a grotesque reversal his vulnerable flesh now lay outside his skeleton.” The tongue inside his mouth, “a slab of slippery meat,” is revolting to him.

The prime minister recalls, in his previous form, encountering “a small mountain of dung, still warm and faintly steaming. Any other time, he would have rejoiced. He regarded himself as something of a connoisseur. He knew how to live well.” The rest of this passage (“Who could mistake that nutty aroma, with hints of petroleum, banana skin and saddle soap”) would belong, were McEwan a U.S. citizen, in an alternative version of “Best American Food Writing.”

Our human cockroach once lived beneath the Palace of Westminster, the meeting place of the House of Commons and the House of Lords, so he’s used to hearing Prime Minister’s Questions, that excellent English tradition. He recalls “the opposition leader’s shouted questions, the brilliant non sequitur replies, the festive jeers and clever imitations of sheep.”

Once McEwan has established his premise, however, “The Cockroach” stalls. It devolves into self-satisfied, fish-in-barrel commentary about topics like Twitter and the tabloid press. The literary references (a boat involved in an international incident is called the Larkin) are plummy and tortured. By the end, homilies have arrived: “It is not easy to be Homo sapiens sapiens. Their desires are so often in contention with their intelligence.”

The sense one gets is of a driver with his hands at the 10 o’clock and two o’clock positions on the steering wheel, with his hazard lights flashing. The best satire makes you fear for your safety and perhaps your soul. Here the trip feels safe, sanitized, buckled-in.

The political antagonists in “The Cockroach” are not Leavers and Remainers, as they are in the Brexit drama, but Clockwisers and Reversalists. The Clockwisers are the elites, if by that term we mean people who care about reason and science and moderation and the cultural reporting in The Guardian. The Reversalists are lusty populists, yobs with bodacious slogans.

At issue is not Brexit but a program called “reverse-flow economics” that would put England at odds with a) sanity and b) its European allies. It is possible to imagine Eric Idle or Michael Palin, in a Monty Python sketch, as a squeaky-voiced bureaucrat explaining Reversalism to a street sweeper. Since it is difficult to suggest a squeaky Eric Idle voice in print, I will spare you the details of Reversalism except to say that its proponents argue, “If you loved your country and its people, you should upend the existing order.”

The German chancellor hears this scheme, closes her eyes and through an interpreter asks, “Why are you doing this? Why, to what end, are you tearing your nation apart? Why are you inflicting these demands on your best friends and pretending we’re your enemies? Why?” The prime minister pauses to think. “Because. That, ultimately, was the only answer:because.”

This thin novel, as brittle as a cockroach’s exoskeleton, does serve as a reminder that good fiction has already emerged that takes into account the violence and perfidy and shock of the new political manner in the United Kingdom and America.

“How’re you doing, apart from the end of liberal capitalist democracy?” a character asks in “Spring,” the most recent of Ali Smith’s seasonal novels. In German writer Robert Menasse’s “The Capital,” a book about the European Union, we read, in what might be the sentence of the year, “He had been prepared for everything, but not everything in caricature.”

The new

The idea of writing “The Cockroach” probably seemed, in the shower one morning, like a good one. Later, after coffee, it might have occurred to McEwan that suggesting your opponents are cockroaches might be to drop down to their carpet level.

A comic novel we could use is one written from the point of view of Anthony Weiner. (Would that Bruce Jay Friedman were young again.) The trail from Weiner to James Comey and the 2016 election is a subject truly worthy of satire. As filmmaker Errol Morris put it not long ago: “Who would have thought that one man’s irrepressible desire to photograph his penis and to share that with women on the internet could destroy Western civilization?”