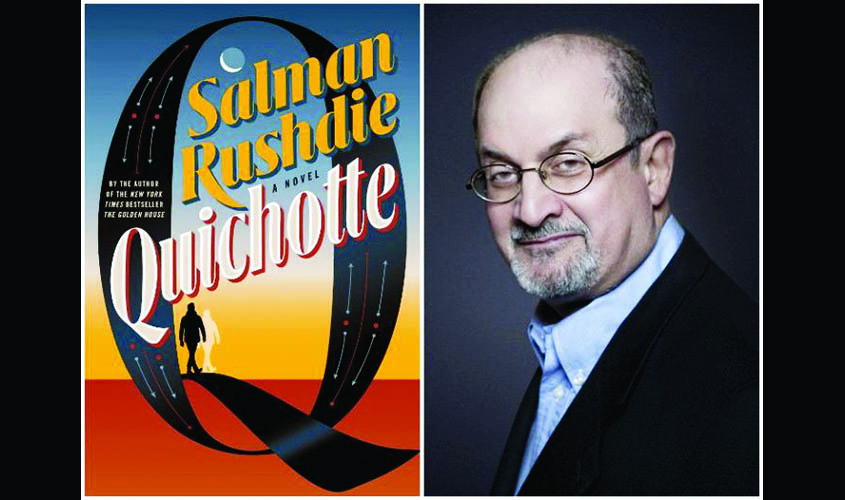

Salman Rushdie’s famous style has congealed in recent years and the flamboyance that once felt so free now seems strenuous and grating. Quichotte is evidence of his decline, writes Parul Sehgal.

How do writers privately define success? Is it a matter of sales, prizes, worshipful reviews? Yes, but only that? Are there more idiosyncratic metrics—a conviction in the value of the work or in the risks taken or, perhaps, the knowledge of the cost of its creation?

“What you hope to do is leave behind a shelf of books,” Salman Rushdie once said, quoting Martin Amis. “You want to be able to walk into a bookstore and say, ‘From here to here, it’s me.’”

A shelf of books. One wishes Amis had been more specific. Rushdie fills a shelf, even two, nicely. He is the author of nearly 20 books—six published in the past 11 years alone, but of diminishing quality. The novels are imaginative as ever, but they are also increasingly wobbly, bloated and mannered. He is a writer in free fall. What happened?

Rushdie made his name on the breathtaking originality of his 1981 novel, Midnight’s Children, the story of a boy “handcuffed to history,” born at the exact second of Indian independence. It was told in the voice of Bombay—rowdy, musical, tender and profane—a new voice for a new literature of migration and identity; the wave of writers influenced by the book were called “Midnight’s Grandchildren.” He followed it with Shame, on the birth of Pakistan, his angriest, funniest, finest novel, to my mind. His next, The Satanic Verses, sealed his literary immortality. The Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa and sent the writer into hiding for nine years—“a fretful, scuttling existence,” as he described it in his memoir, Joseph Anton.

That famous style has congealed in recent years; the flamboyance that once felt so free now seems strenuous and grating. “If he had a fault, it was that of ostentation, of seeking to be not only himself but a performance of himself,” Rushdie writes of a character in his novel The Enchantress of Florence, which could read like stinging self-critique. The later books—Shalimar the Clown, Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights, The Golden House—are all tics, technique and hammy narration that try to toupee over patchy stories, exhausted themes, types passing as characters. For a writer so frequently praised for ingenuity, Rushdie actually follows a formula of sorts. You could make yourself a bingo card: Classic Novel or Myth used as Scaffolding, Femme Fatale, Story within the Story (recounted by a Garrulous Narrator), Topical Concerns, Defense of Hybridity.

Let’s play. The new novel, Quichotte is a retelling of Don Quixote (there’s our Scaffold), with debts to Back to the Future, the Odyssey, Lolita, Pinocchio, the Eugène Ionesco play Rhinoceros, and—why not—the 12th-century epic, The Conference of the Birds. Our hero, a travelling salesman of Indian origin, becomes addled by his obsession with American television (in the original, the Don is addicted to heraldic romances). He begins to believe himself an inhabitant of “that other, brighter world” and resolves to win the heart of a beautiful television host (meet our Femme Fatale), Salma R. He sets off in pursuit of his beloved and channels for himself a companion, a son he calls, naturally, Sancho. In their quest they encounter an America of Trump voters and vicious racism (allowing for that Defense of Hybridity) and become tangled in a subplot involving the opioid crisis (Topical Concerns—check!). This story is revealed to us as a work in progress, however, the creation of a second-rate crime writer, another uneasy Indian in America who writes under the name Sam duChamp (aka our Garrulous Narrator), who has some unfinished business back home.

I didn’t even mention the mastodon invasion. Or the rip in the cosmos. Or the character inspired by Elon Musk. Or the unhappy appearance, toward the end of the book, of a Jiminy Cricket-type character. “This isn’t really happening,” Sancho says. This isn’t really happening, I thought.

Of all genres, fantasy, E.M. Forster has argued, requires perhaps the greatest adjustment on the part of the reader, a special suspension of disbelief. It is not necessarily a great adjustment, but it must be accounted for, and it must be made, otherwise the reader will be left on shore, watching the author’s proud, meaningless exertions with increasing detachment and coldness. When Rushdie’s previous books have succeeded, it is because he has been guided by this awareness and found ways to entice us on board, to poke fun at his own excesses. In Midnight’s Children, blunt Padma performs the function of in-house literary critic: “Here is Padma at my elbow, bullying me back into the world of linear narrative, the universe of what-happened-next,” our garrulous narrator tells us.

The ability to believe in the preposterous is, of course, at the very heart of Don Quixote, called the first modern novel with its commentaries on fiction, metafiction and reality. “He doubts everything and he believes everything,” Don Quixote says of Sancho Panza, a fine precondition for reading fantasy. “It is so, it isn’t so,” Arab storytellers would traditionally begin their tales, as Rushdie writes in The Satanic Verses. There are feints at exploring what this threshold might mean at a time when notions of truth and reality seem so tattered. But Rushdie’s narrative impulses are centrifugal; they lie in tossing in celebrity cameos and literary allusions, in sending new plots into orbit in the hope they might lend glitter and ballast to a work sorely in need of both, sorely in need of tethering to the world, the concerted thinking and feeling of realism, not magic.

As Cervantes’ Don Quixote tells Sancho: Teeth are more precious than diamonds.

© 2019 THE NEW YORK TIMES