An anthology of writings and photographs focused on the life and work of sculptor Meera Mukherjee was launched earlier this week at the India International Centre in Delhi. The book serves as the perfect tribute to an iconic modernist, writes Bhumika Popli.

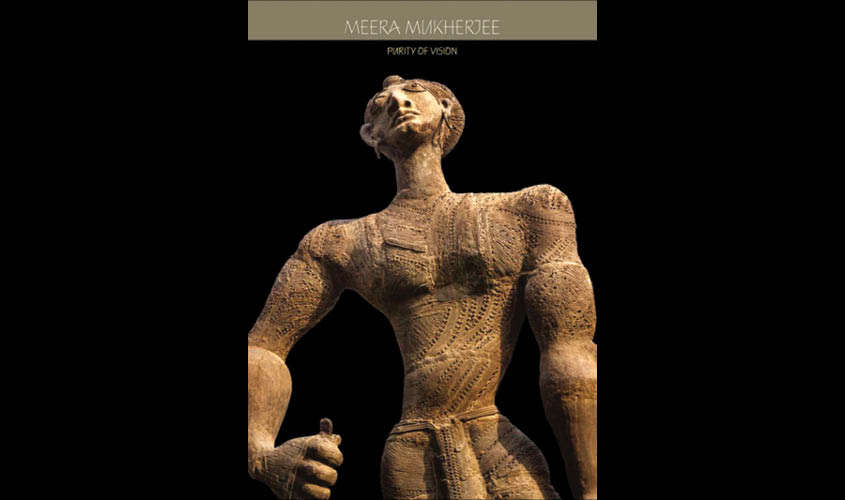

Purity of Vision, a comprehensive anthology that summarises the work and life of artist Meera Mukherjee (1923-1998), was launched at Delhi’s India International Centre earlier this week.

Chiefly known for her sculptures, Mukherjee also dabbled in paintings and kantha works—an embroidery-based form—in her lifetime. The book, which encapsulates her oeuvre, includes 150 images of sculptures, paintings and kantha artworks by Mukherjee, along with nine essays on her art written by close associates. A section of the book, entitled “Meera on Art”, comprises diary entries and letters written by the artist. This part is meant mainly for those looking to get an insight into Mukherjee’s thoughts on art.

As a sculptor, her mediums of choice were bronze, clay and ceramic, in this order of preference. Her themes touched upon everyday life, historical figures and spirituality. The ordinariness of her surroundings was a constant trope in her art. For her figurative work, she found inspiration the working class—in labourers, boatmen, carpet weavers. She also depicted the female figure quite often in her sculptures. The artist, who was well-versed with classical music and used it as one of her motifs as well. She made sculptures depicting veena, sitar and percussion players, Nataraja and Baul singers among others.

At the book launch in Delhi, Reena Lath, director, Akar Prakar gallery, introduced Mukherjee to the audience by saying, “We should celebrate the fact that she is one of the most important women sculptors we had in the country, who had an academic German training but came back more Indian than ever before, and so established a language of her own, in spite of the environment of the ’60s when everybody was moving to the West.”

Mukherjee, in 1953 received a scholarship to study at Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Munich, Germany. But just after completing her four-year course she chose to move back to India. She wanted to seek inspiration in her native land. A question posed to her by her professor, Toni Stadler, who trained her in sculpture, was a deciding factor for Mukherjee to return. He had asked her, “Your country is so rich artistically, and yet you work in the style of the West. Why is that?”

Back in India, Mukherjee blended the folk traditions of the country with a style that was distinctly modern. She learned dokra metal casting and kantha quilting process from artisans and integrated that knowledge in her work. Art scholar Dr Nandini Ghosh, in her introduction of the book, records Mukherjee’s respect for our artisanal culture. We read, “In Meera Mukherjee’s opinion

Mukherjee could easily relate to India’s small-town artisans. As she once wrote, “I have learned from them—their life and craft—their craft entirely embraces and encompasses their life.”

At Delhi’s ITC Maurya, the 11-foot sculpture, titled Ashoka at Kalinga, is among Mukherjee’s most critically-acclaimed artworks. One of her friends, Maja von Rosenbladt, records the artist’s joy upon receiving praise, from a group of “rural viewers”, for this sculpture.

Mukherjee had said, “This is the most genuine critical acclaim I could ever have. The labouring class who admired the technicalities of my work know the sheer toughness of the job, the physical effort that has gone into erecting the sculpture piece by piece… It’s an honour to be a craftsman, the bearer of a long tradition of a life devoted to creating and surviving on that.”

Georg Lechner, former director of Max Mueller Bhavan, at various centres across India helped organise exhibitions of Mukherjee’s work. At the Delhi event, Lechner called Mukherjee as “an Indian artist of Expressionism”, which according to him is still not “fully understood in India about the artist.” He also talked about the self-critical nature of the artist which was similar to her teacher, Tony Stadler. Reading from his essay, Lechner said, “There were even moments before the opening of an exhibition when she was so self-critical that she was inclined to give them [the sculptures] away for free, should anybody care to have them.”

Mukherjee never intended to be an artist, but to create works of art by remaining free from any external obligations. In her own words, “If I am unable to become an intellectual […] if I do not become an artist, nobody can turn me into one by force. If I am an ordinary human being, then I will continue to do the ordinary chores, and remain satisfied and happy with it. I did not have an enormous ambition; I did not wish to become a great artist. Whatever be my standard as a human being, I will only desire that which I feel good about.”

Purity of Vision is published by Mapin in collaboration with Delhi’s Akar Prakar Gallery, Emami Art and Raza Foundation.