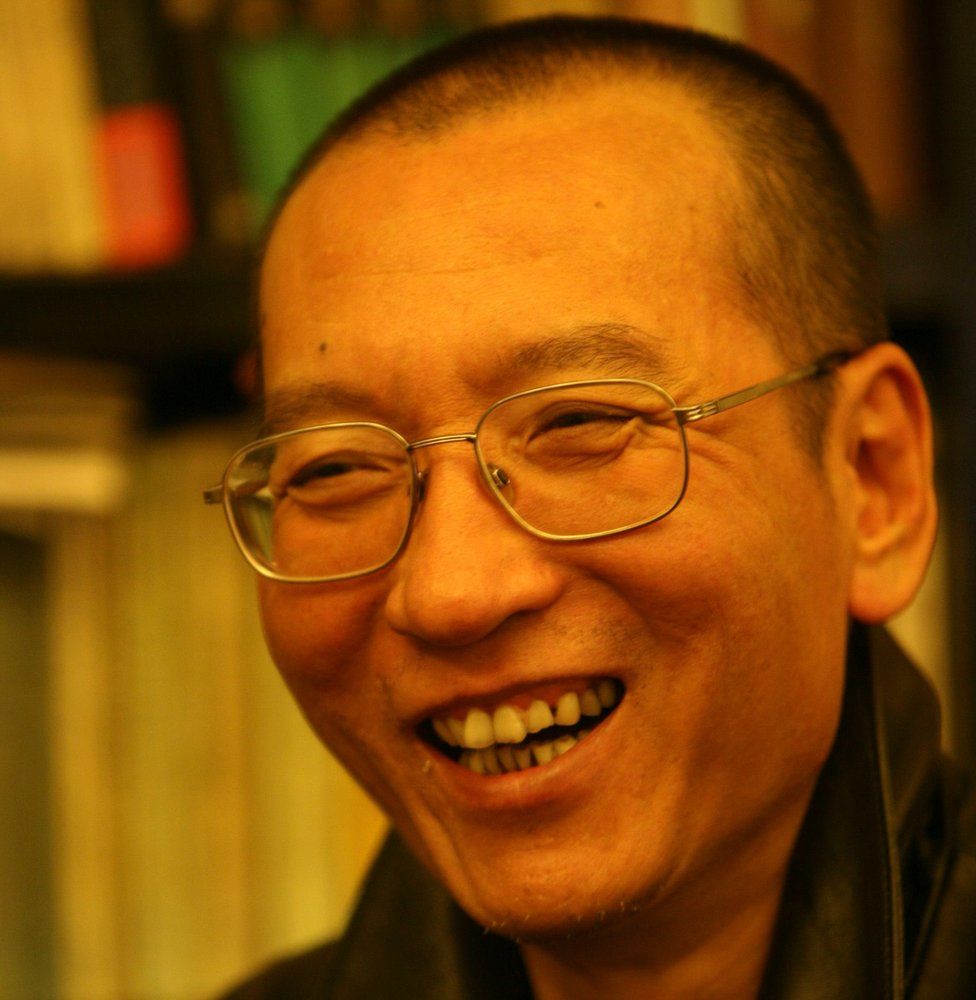

It is no exaggeration to say that Liu Xiaobo, Nobel Peace Prize winner, was murdered by the Chinese Communist authorities.

As a personal friend of Liu Xiaobo’s, I certainly miss him more strongly on this, the five-year anniversary of his death. At the same time, I greatly regret to see that the international community’s memory of Xiaobo seems to be gradually fading. Not only are there fewer articles of remembrance and nostalgia on the Internet, but among the many

This is particularly significant in two ways: First, Liu Xiaobo, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, was seriously ill in prison but was denied proper medical treatment until the end of his life, when he was denied permission to leave the country for specialized treatment. It is no exaggeration to say that he was deliberately murdered by the Chinese Communist authorities. This is not only unprecedented in the history of the Nobel Peace Prize, but is also a heinous act of human rights persecution, wicked conduct that makes one bristle with anger. Yet today, the international community seems to have taken little effective action against the Chinese Communist Party for such a grave evil. When Xiaobo died, there was a proposal in the United States Congress to rename the road in front of the Chinese Embassy in the United States “Liu Xiaobo Square.” But until now this proposal has not been acted on.

The reason for not forgetting Liu Xiaobo is not only to commemorate a hero who sacrificed his life for democracy, but also to remind the world that the Chinese Communist Party has repeatedly crossed the bottom line of the civilized world and has repeatedly committed unprecedented and terrible atrocities. We should not forget what the Chinese Communist Party has done because of the passage of time. The outside world should more importantly realize that as long as China remains under the totalitarian rule of the Chinese Communist Party, the tragedy of Liu Xiaobo will be repeated in the future. Do not forget Liu Xiaobo, and remind the world not to think that Xi Jinping did all these bad things single handedly. You should know that the arrest of Liu Xiaobo and the heavy prison sentence he was given took place when Hu Jintao was Communist Party leader. While we are denouncing Xi Jinping orally and in writing for pushing his reactionary policies, some people are beginning to miss the Communist Party rule of Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao. If you still remember the person who initiated the death of Liu Xiaobo, you will know that the evil of the Chinese Communist Party is not only a personal problem, but also a systemic one. As long as the system of single party dictatorship is not confronted and resolved, no one can improve the human rights record of China.

Second, Liu Xiaobo should not be forgotten because he has symbolic significance. He represents the kind of force of civil society that has grown tenaciously in between the cracks of brutal state violence over the past 40 years. With the Liu Xiaobo-initiated Charter 08 as a standard, we have seen the growth of popular resistance in China. After Xi Jinping came to power, he dealt a crushing blow to civil society in China, leaving many people without any hope for civil resistance in China. But if we understand Liu Xiaobo’s process of personal struggle, we will know that even in the most difficult and darkest period after 4 June 1989 Tiananmen massacre, the fire of resistance has never been extinguished among the Chinese people. The fact that Liu Xiaobo has received the highest recognition by the international community shows that the power of Chinese civil society was once generally acknowledged by the outside world.

Charter 08 is a manifesto initially signed by 303 Chinese dissident intellectuals and human rights activists. It was published on 10 December 2008, the 60th anniversary of the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopting its name and style from the anti-Soviet Charter 77 issued by dissidents in Czechoslovakia led by eventual President Vaclav Havel. Since its release, more than 10,000 people inside and outside China have signed the charter. After unsuccessful reform efforts in 1989 and 1998 by the Chinese democracy movement, Charter 08 was the first challenge to single party rule that declared as its goal the end of Communist Party dictatorship. It has been described as the first one with a unified strategy. In 2009, one of the authors of Charter 08, Liu Xiaobo, was sentenced to eleven years’ imprisonment for “inciting subversion of state power” because of his involvement. A year later, Liu was awarded the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize by the Norwegian Nobel Committee. Seven years later in July 2017, he died of terminal liver cancer in prison after having been granted medical parole. The fire of resistance has never been extinguished in China’s civil society.

Although the present situation is more perilous than ever, we can see from the Chinese Internet that civil discontent still exists, and the power of Chinese civil society has never disappeared. The Chinese Communist Party can eliminate one Liu Xiaobo, but China cannot have just this single courageous person. Not only should we not lose confidence in the forces of domestic resistance in China, but we should actively support the domestic resistance movement. As the most symbolic representative of China’s resistance movement, commemorating Liu Xiaobo is a process of constantly inspiring new Liu Xiaobos to emerge. Therefore, I believe that it is critical not to forget Liu Xiaobo.

Wang Dan was born in Beijing in 1969. After entering Peking University in 1987, he was a politically active student in the history department, organizing “Democracy Salons” at his school. When he participated in the student movement that led to the 1989 pro-democracy protests, he joined the movement’s organizing body as the representative from Peking University. As a result, after the June 3-4 massacre, he immediately became the “most wanted” on the list of 21 fugitives issued. Wang went into hiding but was arrested on July 2 the same year, and sentenced to four years’ imprisonment in 1991. After being released on parole in 1993, he continued to write publicly (to publications outside of mainland China) and was re-arrested in 1995 for conspiring to overthrow the Chinese Communist Party and was sentenced in 1996 to 11 years. However, he was released early and exiled to the United States. Wang resumed his university studies, starting school at Harvard University in 1998 and completing his Master’s in East Asian history in 2001 and a PhD in 2008. He also performed research on the development of democracy in Taiwan at Oxford University in 2009. From August 2009 to February 2010, Wang taught cross-strait history at Taiwan’s National Chengchi University as a visiting scholar. He then taught at National Tsing Hua University until 2015. He is now the director of the Dialogue China think tank.

Translated from Chinese by Scott Savitt.