The critical moment will come around October. By that time, Russia would have consolidated their hold on the occupied territories and perhaps even launched fresh actions towards Kharkiv or Odessa. By then, the Ukraine counter-offensive in the south would have also run its course.

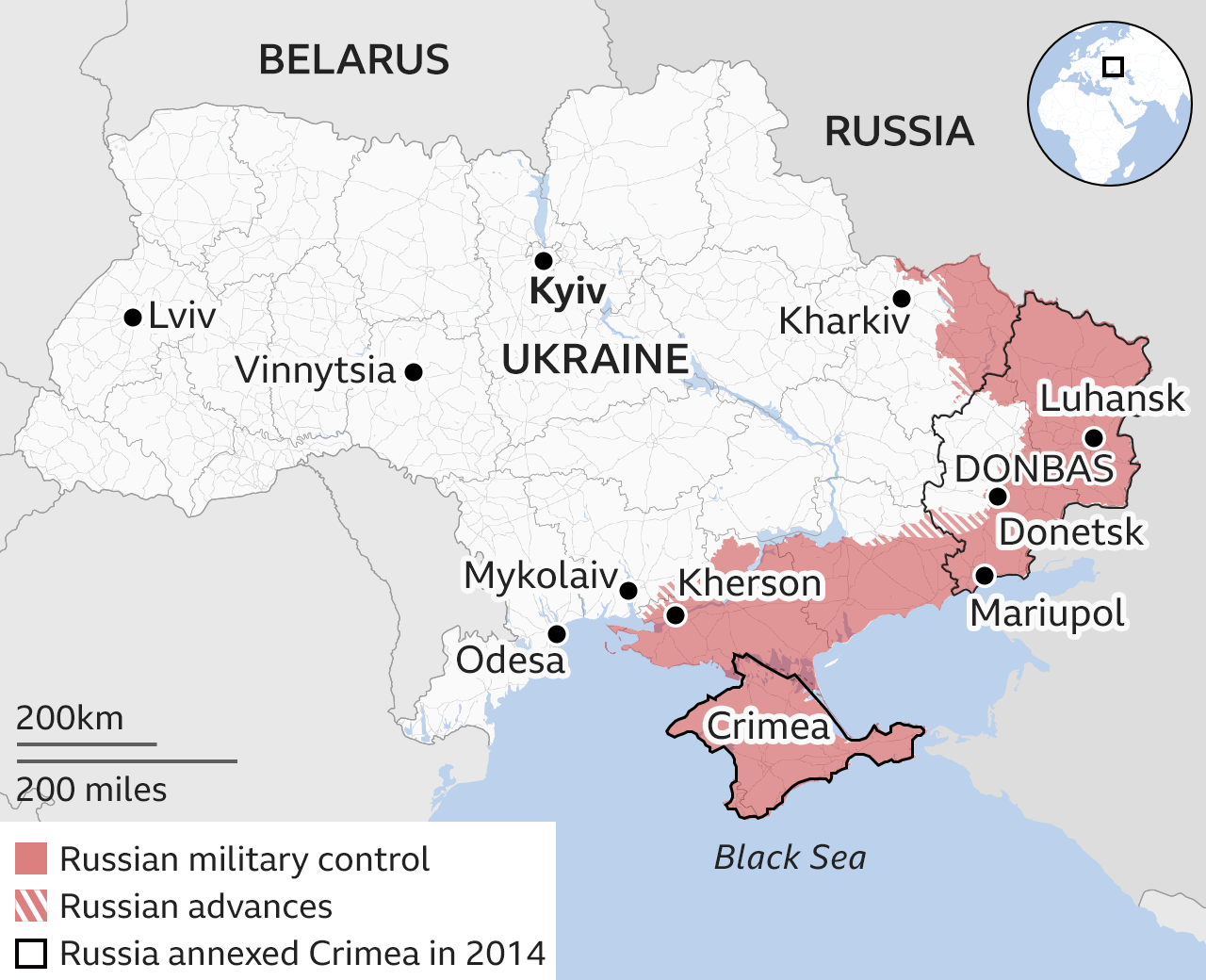

NEW DELHI: Five months into the war and there is little clarity of how it could end. With the capture of Severodonetsk, and its twin city of Lysychansk the Russians have gained control of Luhansk Province. Their focus has been shifting towards the Donetsk Province (the second province of the Donbas—Russia’s slated objective) where they have closed in on the critical towns of Slovyansk and Kramatorsk. If Donetsk comes into Russian hands, they would have established control over all of Eastern Ukraine—from Kharkiv in thenorth all the way down to the Black Sea Coast—a swath of land 1,200 kilometers long and almost 200 kilometers deep.

Yet, it will not be easy. The gains have come in after five months of slow fighting, which had claimed a high toll of men and equipment. The Ukrainians have also launched their own counter offensive in the south towards the town of Kherson—the first town occupied by the Russians during their offensive. The offensive has succeeded in drawing over a dozen Russian Battalion Tactical Groups from the east towards the southern front. This has staved off the immediate threat to Donetsk as the focus shifts towards the south. But will the Ukrainian offensive be able to attain a decisive success? It has moved along a 100-kilometer-long front from Mykolaiv to Kherson in a series of small localized actions supported by long range artillery, but has advanced only around 11 kilometers in a fortnight. (Very akin to the Russian advance in Donbas). The targeting of three key bridges on the Dnipro River has cut off all Russian troops west of the river line and forced them to withdraw, but Kherson has not been recaptured. In fact, the Russians have dug down, and recapturing Kherson would require a sustained offensive with more troops and equipment. It thus seems more likely that the Ukrainian offensive will creep forward around 20-30 kilometers eastwards, but then, both sides will consolidate along the Dnipro River line. At best, the Ukrainian offensive would have improved their defensive posture in the south and reduced the threat to the vital port of Odessa (from where the first ships carrying Ukrainian grain have finally sailed). It has also reduced some of the pressure on Donetsk. But now what?

Many analysts expected the Russians to take over Donetsk in a month or so, using their standard tactics of massed artillery fire and creeping advances. This may now be delayed with troops being diverted to the southern sector, but is still within Russian capabilities. It was anticipated that after capturing Donbas, Putin could declare the attainment of his war aims and call off the operation. But with his dangerous unpredictability, he could have got even more ambitious and pushed on towards Odessa, Kharkiv and perhaps even Kyiv for “a complete victory”. Any Russian push beyond the Donbas and the south will be a little difficult now, since the troops are exhausted after six months of campaigning and fresh troops not available, since Putin has refrained from a general mobilization so far. Perhaps the Ukrainian counter-offensive could push the Russians back across the frontier—their stated aim of the operation. But that seems difficult, and at most the Ukrainians could only make local gains. In the most likely scenario, both sides could dig down in the positions they occupy and that line could become a de facto LOC (the line dividing Russian and Ukrainian troops is already called the LOC—for Line of Contact.) The fighting could then recede, but the conflict could continue indefinitely in a state of “frozen conflict”.

What were Putin’s aims when he launched the operation and how close has he come to attaining them? The seizure of the Donbas and other areas considered “historically Russian” was one of the major objectives of the war. He has already got over 20% of Ukraine’s richest territory under Russian control. In these areas a major “Russification” process is already underway. Pro-Russian municipal councils have been set up, pay and pensions are being distributed in Rubles instead of the Hryvnia; Ukrainian TV and radio channels have been blocked and replaced by Russian ones; and internet services are routed through Russian servers. A referendum is on the cards for the formal amalgamation with Russia. Like he did with the Crimea in 2014, these occupied territories will be simply absorbed into Russia in a fait accompli.

The destruction of Ukraine’s war-waging potential and change of regime was another major aim of the offensive. Ukraine has suffered heavily and is losing over 200 soldiers every day. They have admitted to losing over 1,300 fighting vehicles, 400 tanks and 700 artillery pieces, greater losses than what was previously imagined. To some extent these losses have been replaced by the influx of over 200,000 reservists and heavy Western aid (now estimated to be over $70 billion), but is not enough. Russia too has suffered heavy losses of over 20-25% of its fighting forces. The war of attrition has taken a heavy toll on both sides and though Russia can sustain it longer, it will reach saturation point if the war goes on much longer.

Putin may have succeeded in his initial aim of keeping Ukraine out of NATO, but conversely his actions have strengthened NATO with even Sweden and Finland all set to join it. By successfully usurping a large chunk of Ukraine, he has cocked a snook at the alliance but with NATO increasing its deployment in Europe, Russian security has been further endangered, rather than secured. His actions have also irreparably damaged Russia’s international

So, how does one see the war panning out and in what time frame? The critical moment will come around October. By that time, Russia would have consolidated their hold on the occupied territories and perhaps even launched fresh actions towards Kharkiv or Odessa. By then, the Ukraine counter-offensive in the south would have also run its course. It would make gains all right, but is unlikely to push the Russians completely out of the occupied areas. Whatever gains either side makes would have to be done before that time. Both sides thus want to occupy a favourable defensive line before that, where they could dig down and consolidate. Large scale offensive maneuvers will not be possible when winter sets in and then the spring thaw—Rasputina—will curb effective operations till around end March.

Whatever be the position till end October is thus likely to be the Line of Control of the war. Ukraine has stated that it would not halt operations till Russia vacates all the occupied territories (including Crimea) and the war could become a longer war of attrition. Both sides would hold positions opposite each other and continue firing, raiding and sniping with periodic eruptions—something like the Donbas since 2014. (And the LOC between India and Pakistan). This could be a long interminable war, which could form a new LOC in Europe, with all its attended fears and dangers.

NATO and the Western allies are unlikely to get directly involved in spite of moral and materiel support. A long war which weakens Russia, suits them and they will continue arming Ukraine and wage their proxy war till the last Ukrainian. Sophisticated weapons, like the long range HIMARS rocket artillery system with GPS guided munitions, have helped the Ukrainians hit ammunition dumps, rail and road hubs, and even strike a Russian airfield deep in the Crimea—but it is not enough. To truly turn the tide, the Ukrainians need twice the quantity they are receiving now. If the war continues longer, the western nations will be reluctant to shed any more of their hardware and deplete their own reserves. Aid could thus gradually dwindle and would not suffice to change the overall situation.

A possible end state to the war could be the Russian occupation of Donbas and the area along the southern coastline up to the line of the Dnipro River. The Ukrainian counteroffensive could push the line a few kilometers eastwards, but would be unlikely to evict the Russians completely. But then this war has surprised many, with its twists and turns, and could change course again. The critical time lies from now till October. That period will decide whether Russia achieves its aims and takes all of Donbas—or even whether it expands the scope of the war and heads towards Odessa and Kharkiv. It will also determine the gains the Ukrainian counter offensive makes and decide the Line of Control between the two sides. The outcome of this period will determine whether the war will finally come to an end or whether it will continue into the next year and beyond, in an interminable state of frozen conflict.

Ajay Singh is a noted writer who has authored five books and over 200 articles. He is a recipient of the Rabindranath Tagore International Award for Art and Literature 2021.