The SRs mechanism has been in place since 2003 and since then 23 meetings have been held.

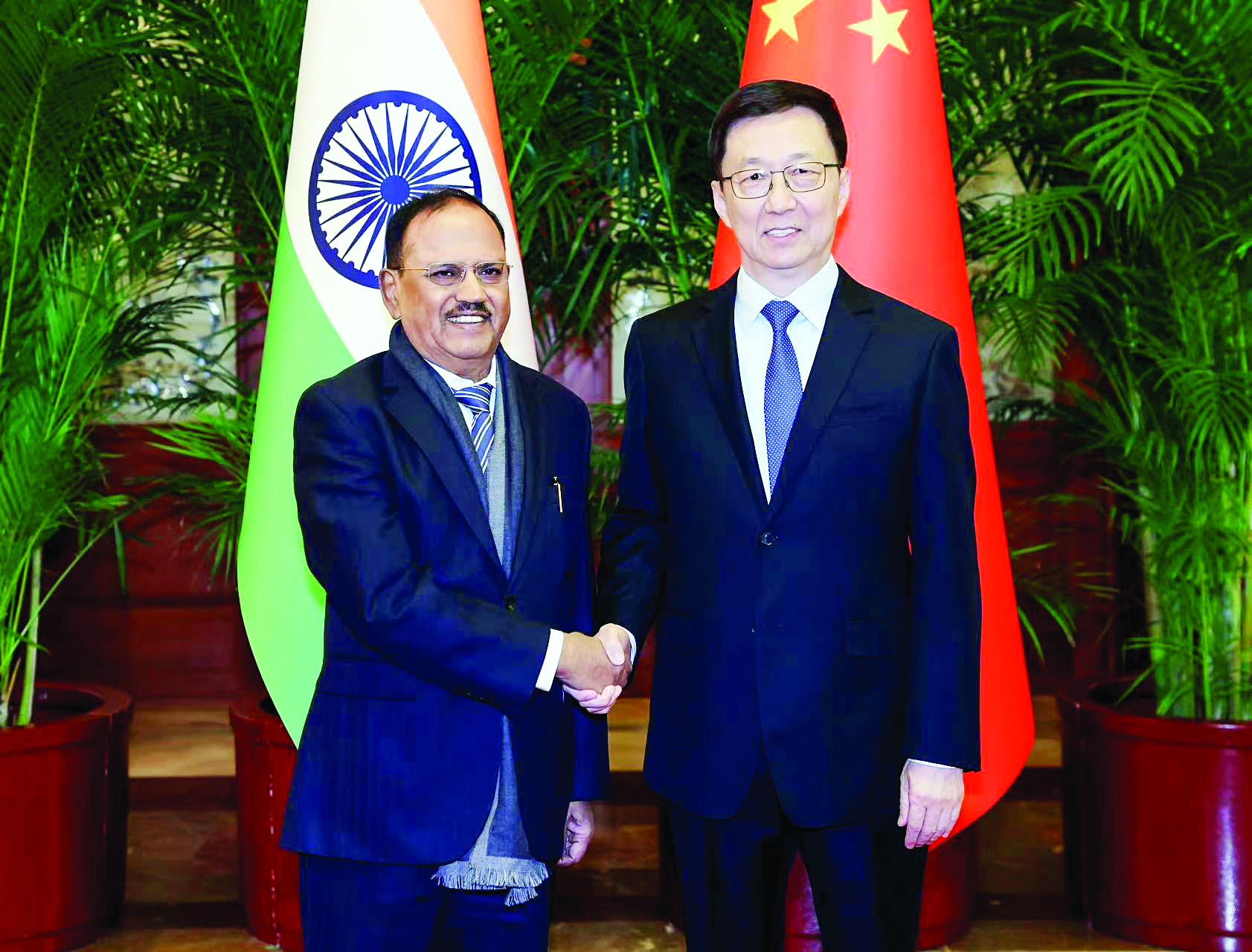

Following the 23rd round of talks between the Indian Special Representative and National Security Advisor Ajit Doval and the Chinese Special Representative, Member of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee and Director of the Central Foreign Affairs Office, Wang Yi on 18 December 2024 in Beijing, both sides, according to China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA) “reached six consensuses in a positive and constructive manner”. The Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) in its press release stated that the Special Representatives (SRs) “provided positive directions for cross-border cooperation and exchanges including resumption of the Kailash Mansarovar Yatra, data sharing on trans-border rivers and border trade”.

The SRs meeting is an outcome of the Modi-Xi meeting in Kazan on 21 October that broke ice between the two sides post Galwan clashes and paved way for normalisation of bilateral relations. An agreement was reached on patrolling arrangements along the Line of Actual Control (LAC), especially in Depsang and Demchok areas, that led to disengagement and de-escalation of the frontline troops. India had resolutely advocated that restoration of status quo ante and peace and tranquillity along the LAC was a prerequisite for normalisation of relations. China, on the other hand, had argued that the border should be placed in an appropriate position in the bilateral relations.

The “six consensus” reached between the SRs according to the MoFA are: 1) the border issue should be properly handled from the overall situation of bilateral relations and should not affect the development of bilateral relations, both sides agreed to continue to take measures to maintain peace and tranquillity in the border areas; 2) to seek a fair, reasonable and mutually acceptable package solution to the border issue in accordance with the political guiding principles; 3) to further refine the border area control rules, strengthen confidence-building measures (CBMs), and achieve sustainable peace and tranquillity on the border; 4) both sides agreed to continue to strengthen cross-border exchanges and cooperation, promote the resumption of Indian pilgrims’ pilgrimage to Tibet, China, cross-border river cooperation and Nathula border trade; 5) to further strengthen the construction of the SRs mechanism, strengthen diplomatic and military negotiation coordination and cooperation, and require the Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination on India-China Border Affairs (WMCC) to do a good job in the follow-up implementation of this special representatives’ meeting; and 6) to hold a new round of SRs meeting in India next year.

The SRs mechanism has been in place since 2003 and since then 23 meetings have been held. During the fourth round in 2004, it was proposed to establish the political parameters and guiding principles for resolving the border issue, then establish an agreed framework for a boundary settlement of these guiding principles, and finally demarcate the border on the ground. Of these three-steps, the first was achieved during the fifth round, and the agreement was signed during Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao’s India visit in 2005. The agreement while advocating the “package deal” for the resolution of border issue also stipulated that the two sides should strictly respect and observe the LAC and work together to maintain peace and tranquillity in the border areas. Since then, no real progress on border issue has been made, both sides have failed to reach a consensus on the “framework for border settlement”. The SRs mechanism has ended up a bit of strategic dialogue between India and China that not only touched upon bilateral issues but also international and regional issues as could be gleaned from MEA and MoFA statements.

The framework requires a political solution as both India and China are reluctant to make major concessions on all the sectors of the border. Some of the parleys and respective positions of India and China pertaining to border negotiations could be found in the Choices (2016) by Shiv Shankar Menon and Strategic Dialogue (2016) by Dai Bingguo, both had negotiated the border issue in capacity of the SRs. According to Dai Bingguo (2016, 269), who negotiated the border issue with four Indian SRs between 2003 and 2013, “both sides lost an opportunity to resolve the border during early rounds of the SR talks”. As there was a change in government in India, the momentum was lost. In 2004, “when I met Mishra, he told me, I would have never wished to pass the baton to the others, what is a pity”, writes Dai. After signing the agreement on the political parameters in 2005, next eight round were spent in finding the framework, but without any success. During the 9th round, Dai claims having told Narayanan “I do not wish to discuss it [the border issue] to the 99th round, and I do not wish to keep it for our future generations”. During the 10th round in 2007, Dai tells his Indian counterpart that “we must fully consider Chinese people’s historical and national sentiments towards the Eastern Sector”. After this round according to Dai, the main focus of the SRs was to keep the channels of communication open, and safeguard the atmospherics.

It could be discerned from Dai’s assertions and formulations that though China remained interested in reaching an agreement with India on the border, but was unwilling to accept the McMahon Line in the Eastern Sector in its totality; he was merely reiterating China’s stated position. The crux was China wanted India to make concessions in Tawang, which India ruled out. India hoped that by inserting article VII in the political parameters, China would appreciate India’s position. With such an approach from both the sides, it was impossible to reach an agreement on the proposed framework. Even though both sides have been reiterating that the Special Representatives are resolved to intensify their efforts to achieve a fair, reasonable and mutually acceptable solution to the India-China boundary question at an early date, however, it seems that Article VII of the Agreement that stipulates “in reaching a boundary settlement, the two sides shall safeguard due interests of their settled populations in the border areas” has essentially jeopardized the principle of give and take. In order to nullify the clause, China has come up with the idea of border villages and has continued to build pressure on India in the Western Sector.

The “package settlement” remains one of the most viable frameworks for resolving the issue, which according to Menon (2016, 30) is “give-and-take on the basis of the status quo.” The fundamental reason the boundary settlement is taking so long, in Menon’s view is that “both sides think that time is on their side, that their relative position will improve over time.” He believes an assertive China is unlikely to seek an early settlement of the boundary issue no matter how reasonable India may be, even though the technical work has all been done [by the SRs]. The “technical work” here could be referring to the agreed framework that was never signed by the two sides. Therefore, the purpose for which the SR mechanism was created has certainly been lost. The mechanism has been reduced to yet another CBM in the line of many others on the border and demands re-evaluation by both the sides.

* B.R. Deepak is Professor, Center of Chinese and Southeast Asian Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.