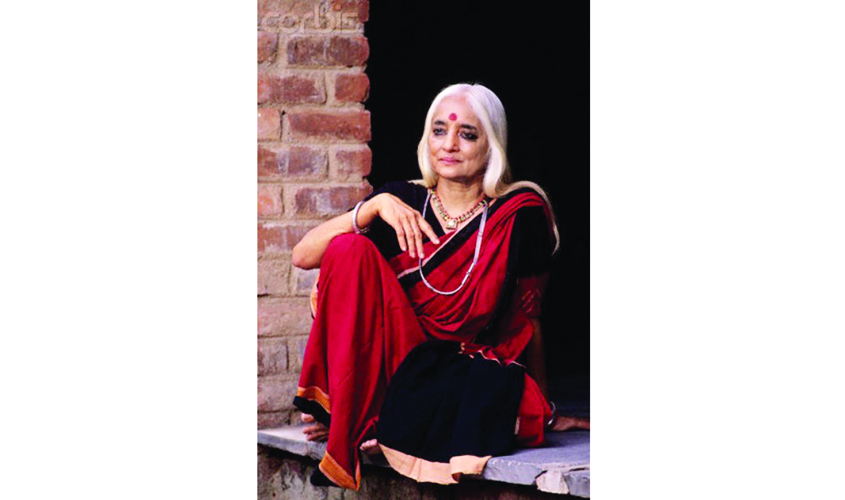

As this year also happens to mark the 10th death anniversary of the legendary dancer-choreographer Chandralekha, Gati on 13 October decided to host an evening of remembrance at the Odd Bird Theatre, reminiscing her ten major choreographic explorations that had taken place in a period of over 20 years. Revitalising her understanding of body and movement by interlacing it with principles from other native physical disciplines like Kalarippayattu and Yoga and rejecting the narrative mainstream, Chandralekha had created an entirely new concern for abstract ideas of space, time, sexuality and erotica in Bharatanatyam. Her productions like Angika, Lilavati, Prana, Sri, Yantra, Mahakal, Raga, Shloka and Sharira are distinguished by their conceptual complexity, path-breaking choreography and a stunning visual sensibility. Her collective body of work is today considered the yardstick by which Indian contemporary dance is measured.

The present tribute, hosted by Gati, comprised photographs by her close associates, the late artist/designer/photographer Dashrath Patel and writer/photographer Sadanand Menon. It also included representative photos from Raghu Rai, Peggy Jarrell-Kaplan, Bernd Merzenich and Abul Kalam Azad.

Sadanand Menon, one of the trustees of the Gati Dance Forum and a longtime friend and collaborator of Chandralekha put a context to the event, saying, that she represented the coming of age of the contemporary dance movement in India. He added that the current phase of Indian contemporary dance could be traced to the bursting on to the scene of choreographers like Chandralekha and Kumudini Lakhia in 1984 at the East-West Dance Encounter.

“Today modern Indian dance has reached a point where questions that were raised by CVhandralekha ages ago need to be asked. Gati is creating that space where self enquiry and self contestation can happen again,” said Menon.

He added: “Most of the photographs that you will see in this exhibition, curated by me were taken while Chandralekha’s performance was on. But you must know that whenever it came to photographing her works, she would say, ‘don’t interfere with this horrible, mechanical two dimensional instrument. What I do with my body can never be captured by a camera.’ The still and the video camera were an anathema for her.”

One of the earliest pictures displayed here was taken in 1984, which is the era when Chandralekha comes back to dance after a long gap, almost after a 24-year-old long gap. Her 1971 performance called ‘Navagraha’ with Kamadev, one of India’s finest and greatest male dancers where they perform a duet was a homage to the nine planets. It was also part of her quest for trying some non-methodological, non-narrative kind of theme and content. After that there was a 12 year gap and in 1984, she was invited in Bombay by the East-West Dance Encounter, probably the beginning of the contemporary phase of modern Indian dance,” Menon further said.

Sadanand Menon, one of the trustees of the Gati Dance Forum and a longtime friend and collaborator of Chandralekha put a context to the event, saying that she represented the coming of age of the contemporary dance movement in India.

He went on to describe how innovations have been taking place in the domain of Bharatnatyam by the likes of Rukmini Devi Arundale and Kalakshetra in late 1930s, then by Uday Shankar and his Almora school of dance and the making of the film “Kalpana”, but it was the East-West Encounter which broke all conventions. “The East-West Dance Encounter brought together 20 Indian dancers and 20 International dancers and did an eight-day exploration of all kinds of challenges and compositions and performances

It was with this enlightening talk on the legacy of Chandralekha and ideas of critical engagement with contemporary dance traditions in India that Gati Dance academy took the opportunity to initiate the launch of the book, Tilt Pause Shift: New Ecologies of Dance in India. Considering the elusive nature of the ‘contemporary’ in dance, where it is neither a temporal moment nor a static form or style of movement, the book addresses points of evolution in the creation and practice of dance in India today – highlighting new channels of thought and enquiry, shifts in form, and changes in modes of movement and expression. Menon, too, has contributed in this book, besides contemporary choreographers Padmini Chettur and Navtej Johar.

The evening would have been incomplete without the screening of Tana Bana, a 15-minute feature on Chandralekha filmed in 1992, in Chennai, commissioned by PTI-Television , the text/commentary of which was originally written in English by Menon (who was those days the Arts Editor for Delhi’s The Economic Times). Arts Curator Menon mentioned that when PTI-TV had wound up in 1994 and all their tapes and recordings had vanished without trace, the present version that was being screened was originally a direct-from-TV VHS recording. Around 1999, the fungus-affected tape was cleaned and copied on to a DVD by Krissy Biernacki, an American dance student who had spent almost a year in Chennai and had helped Chandra convert some of the other tapes to DVD. As the sole surviving copy of the original, it happened to be an important piece in archival history for researchers, curators, enthusiasts on Chandralekha and Indian dance traditions.