What has Pakistan got for the infrastructure being built, courtesy of Beijing? A gargantuan amount of debt. Islamabad owes China a large portion of its massive foreign debt, now estimated to be about $131 billion.

Seen from the West, Islamabad’s hypocrisy is breath-taking. Quick to criticize India for even the slightest perceived injustice against its Muslim population, there is a stony silence from Pakistan on the genocide being carried out by China against the Uyghur population and other mostly Muslim ethnic groups in the north-western region of Xinjiang. Human rights groups believe China has detained more than one million Uyghurs against their will over the past few years in a large network of what the state calls “re-education camps”, and sentenced hundreds of thousands to prison terms. And what do Pakistani leaders say about these crimes against humanity? Nothing. Zilch.

The reason, of course, is that because of CPEC, Pakistan is so much under the thumb of China that its leaders are terrified of uttering even the tiniest criticism of the regime in Beijing.

It’s now seven years since the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor was launched, part of China’s sprawling infrastructure programme, known as the Belt and Road Initiative. Islamabad fell hook line and sinker for the specious generosity of Beijing, which has resulted in a $62 billion Chinese investment pledge in the CPEC, almost one fifth of Pakistan’s GDP. Perhaps the advice given by Virgil, millennia ago, in his Aeneid when referring to the Trojan Horse, “beware of Greeks bearing gifts”, should be updated to “beware of Chinese bearing gifts”. What has Pakistan got for the infrastructure being built, courtesy of Beijing? Debt—a gargantuan amount of debt. Add it all up and you find that Islamabad owes China a large portion of its massive foreign debt, now estimated to be about $131 billion.

Having been on a drunken spending spree, Islamabad now finds itself not only with serious political corruption and bickering leaders, but also with economic productivity that has fallen to a six-year low, rapidly shrinking domestic revenues and foreign reserves, soaring unemployment and a depreciating currency. And then there’s the matter of servicing that debt.

In June, Islamabad borrowed another $2.3 billion from China to shore up its foreign reserves. The Chinese loan will raise Pakistan’s foreign reserves of $8.2 billion to $10.5 billion and could help save the rupee, which has slumped against western currencies. Pakistan began to receive IMF payments in 2019 under a 39-month loan programme, but the fund has so far given only about half of the $6 billion agreed. In the hope of unblocking the remainder, Islamabad announced a one-off 10% “super tax” on important industries. The Karachi Stock Exchange immediately fell nearly 5% on the news, with analysts predicting that the decision would further fuel inflation, a central concern for households across Pakistan.

But it’s not only inflation which is worrying Pakistanis, it’s also the presence of so many Chinese in their country. Chinese companies awarded contracts under CPEC have mostly used Chinese nationals to carry out the work, thus vastly increasing the number of Chinese faces in Pakistan. In turn, this has created resentment among the local populations, making CPEC a divisive issue, particularly in Pakistan’s periphery. Emboldened by the Taliban’s takeover of Kabul, radical Islamic groups are increasingly targeting Chinese workers, especially in Balochistan, which has become a hotbed of insurgency. Although Baloch militants have been targeting non-Balochi speaking people for over a decade, in recent years they have turned their guns towards Chinese nationals working on CPEC projects. The result has been an increased presence of Pakistan’s army involved in Balochi life, all under the guise of maintaining security.

Security challenges are often a good indicator of the geostrategic relevance of an initiative, and the huge challenge created by CPEC confirms its sensitive importance. The rising levels of tension and violence from Kashmir in the north down to Balochistan, the home of the crown jewel of the project, Gwadar port, have already forced Islamabad to deploy over 8,000 security personnel to protect Chinese workers. This didn’t stop a female suicide bomber blowing up the Chinese Confucius Institute in Karachi in April, killing three Chinese nationals. Last month a bomb planted on a bus killed nine Chinese engineers and an explosion in Quetta targeted the Chinese ambassador, this time without success.

This new wave of militancy is an issue of great concern for both Beijing and Islamabad, as multiple attacks on the CPEC-related projects have not only slowed down the pace of work but have caused considerable distress among Chinese workers. As anti-Chinese sentiment has mushroomed in Pakistan, Beijing has pressed Islamabad to implement appropriate steps to stop attacks on its workers. Beijing has even floated the idea of establishing its own private security company in Pakistan to protect its citizens and the CPEC-related developments. This idea was rejected by Pakistan’s Interior Ministry, assuring Beijing that it will provide sufficient security forces to be able to protect both Chinese citizens and CPEC projects.

The dramatic collapse of Sri Lanka’s economy and toppling of its government last month, has not gone unnoticed in Islamabad. Sri Lanka’s dire situation, caused by spiking commodity prices and a staggering debt, offers a bitter lesson to countries such as Pakistan that are heavily dependent on Chinese loans. Between 2000 and 2020, China had extended close to $12 billion in loans to the Sri Lankan government, mostly for a large number of major infrastructure projects that turned into white elephants. Of these, the prime example is the port in Hambantota, which was effectively ceded to China after the Sri Lankan authorities realised that they couldn’t pay off the loans.

Due to the country’s size, the stakes are even higher in Pakistan, home to the world’s fifth biggest population and a $340 billion economy. So is Pakistan too big to fail? Today the jury is out, but Pakistan risks an outcome far more dangerous than Sri Lanka. To many observers, Islamabad is gambling on the fact that Pakistan is significantly more important to China and the rest of the world than is Sri Lanka. Nevertheless, as debt soars, Pakistani politics have become increasingly turbulent thanks to the actions of its leaders. It has an overreaching military and the population is now deeply polarised. Islamic nationalism is growing in the country, encouraged by a growing cadre of Pakistani leaders bent on turning Islamic militant groups into mainstream actors.

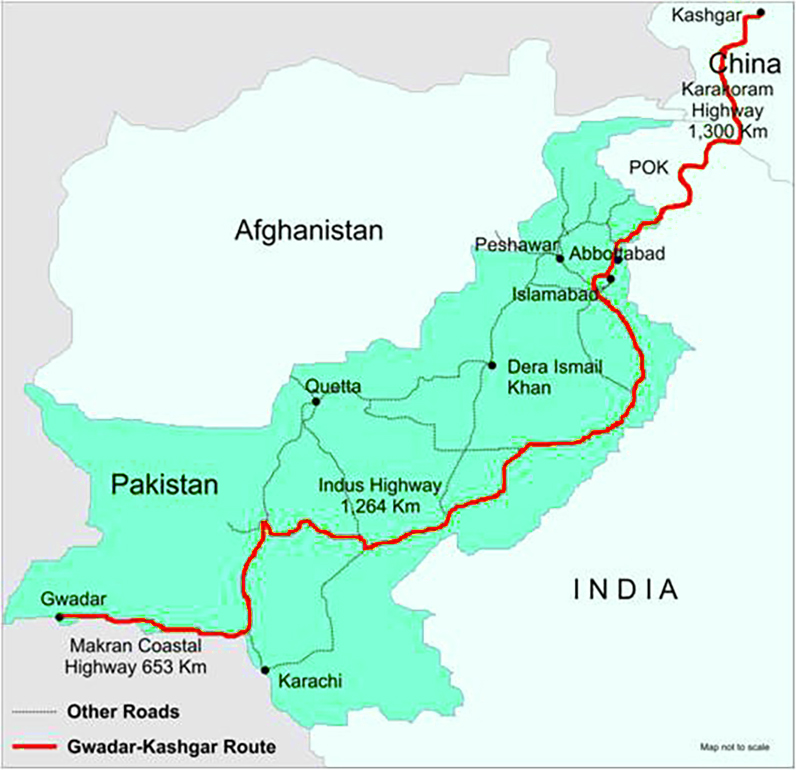

So where do things currently stand? Optimists argue that CPEC, with its 3,000 km long connectivity route of highways, railways and pipelines, will not only improve people’s living standards, but will mend Pakistan’s socio-political fault lines. Realists respond that CPEC projects have done little to boost indigenous employment inside Pakistan. In some cases, projects have resulted in land grabs and displaced scores of local people, generating wide instability. Realists also point to the danger of the Chinese dominated CPEC creating a powder keg of grievances which could explode as ordinary Pakistanis become poorer and angrier. Many are waking up to the catastrophe of becoming so entangled with Beijing’s overseas investment machine, while their leaders look in trepidation at the scale of the country’s huge debt and how they are going to be able to service it.

Meanwhile, sceptics claim that CPEC is nothing more than a Chinese strategic and military expansionist scheme, pointing the finger at Pakistan as a collaborator. They are probably right.

John Dobson is a former British diplomat, who also worked in UK Prime Minister John Major’s office between 1995 and 1998. He is currently Visiting Fellow at the University of Plymouth.