Sukanya Rahman’s new book, Dancing in the Family, is an inter-generational memoir about the dancing careers of her mother and grandmother, and her own education in classical dance.

Dancing in the Family

Sukanya Rahman; Speaking Tiger Books; Pages: 256; Price: Rs 399

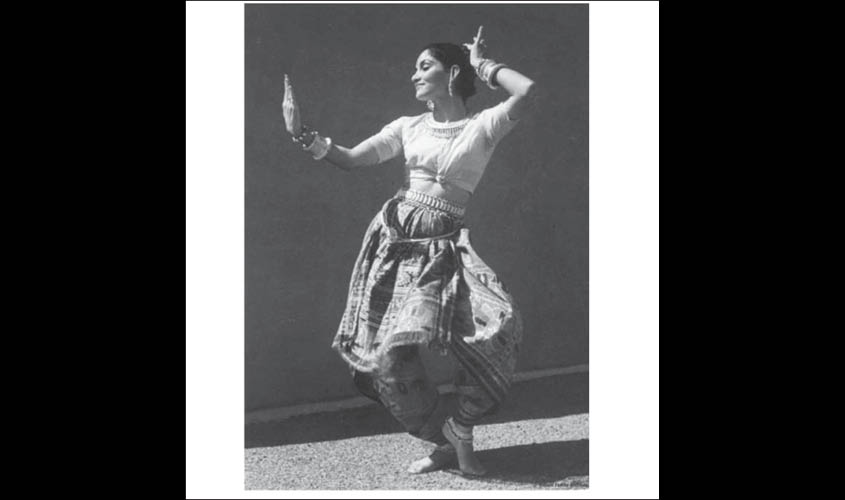

The life of a dancer—as I learned from my grandmother and mother—isn’t always adoring audiences, standing ovations or beautiful garlands of flowers. In my own dance incarnation, there were the inevitable highs and lows. It was when I was recruited as a guinea pig for the Artists in Schools Programme in Maine that I encountered some of my lows. Staggering out of bed at the crack of dawn, painting my face, getting into full costume, and then driving my ancient Plymouth Catalina to an assigned school was a constant challenge. I once arrived at a school in a snowstorm. As I stepped out of my car, smoke began to spew out of the engine. The students, whose faces were glued to the window, screamed in excitement: “The Indian dancer has arrived, the Indian dancer has arrived!”—impressed no doubt at my arrival in a puff of smoke! One of my gigs was an invitation to perform at my sons’ elementary school in Harpswell Island, Maine. When I stepped on stage, the student’s jaws dropped… (Did they think I had descended from the moon?) They received my performance with much enthusiasm and bombarded me at the end with questions: “Why do you have a red dot on your forehead? Why are your feet and the palms of your hands painted orange? Are those real flowers in your hair? Do all the women in India wear bells around their ankles?” Once back home, as we were sitting down to dinner, my older son turned to me and said, “Ma, don’t ever come to our school dressed like that again.” I complied, thinking back to the times the grown-ups in my family had mortified me with their behaviour. My grandmother, Ragini Devi, was especially not one to follow convention.

Some months after her death in 1982, my mother handed over to me for safekeeping Ragini’s most precious possessions. Stuffed into several large shopping bags, bearing the names of an assortment of New York City stores, were bulky photo albums, Bible records of the Parker/Abbott families dating back to 1660, Ragini’s certificate of marriage to my grandfather, a collection of expired passports, old affidavits, documents and a few personal letters. Sifting through the contents of the bags many years later one of the letters, addressed to a “Mrs. Bradley” grabbed my attention. Written from Bangalore on 19 February 1931, the three-page letter described in detail my grandmother’s journey to India, a broken love affair

By the time I came to know my grandmother, she was quite matronly, retired from the stage and struggling to complete her second book on Indian dance. The great-grandmother my two sons remember was a stooped-over old lady who lived in a nursing home in New Jersey, but who was still savvy enough to send them masks at Halloween depicting the rock group Kiss and other current pop icons. I wanted to bring back to life for my children this other Ragini—the beautiful, indomitable young dancer who had poured her heart out to Mrs. Bradley. To sort out fact from fiction, and out of sheer curiosity, I had tried probing my grandmother with questions during her lifetime. But she was always cagey. It was virtually impossible to penetrate the persona she had created. To piece her life together I began by re-reading her first book, Nritanjali, where I uncovered valuable insight into Ragini’s intellectual persona. From the Introduction and Conclusion of her second book, Dance Dialects of India, I learned more about her early passion for dance, for India, and her professional touring days. But even there my mother had to help me ferret out the facts. I pored over microfilms of Ragini’s reviews, articles and programmes that my mother had donated to the Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center. I came across articles at the New York Public Library. I crawled under the bed in our Delhi flat and extracted, from an ancient dust-covered suitcase, crumbling, yellowed newspaper clippings dating back to 1926. I tracked down Ragini’s friends and colleagues. In Delhi, I tried to get Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya to talk about the woman who had run off with her husband, but she was just as cagey as my grandmother was and would keep changing the subject. She would only say that she had great respect for Ragini as an artist, and remember her as a beautiful dancer with especially expressive abhinaya. Ragini’s story is also the story of three generations of women that continues down through my mother and myself. Happily, unraveling my mother’s early life was much easier since she was a lively, nonstop talker. She recalled stories and anecdotes when we chatted over the phone. Strolling with her along some street in New York’s Greenwich Village would trigger dormant memories. One evening when I was visiting my mother in her East Village apartment in New York, we were polishing off a bottle of Bordeaux and eating Chinese takeout while watching TV. Jessye Norman, the incomparable diva, was singing the “Liebestod” aria from the opera Tristan and Isolde. It set off a flood of nostalgia, and my mother began to reminisce over her early romance with my father when she was barely 14. I had a vast collection of interviews my mother had given over the course of her career, both on tape and in print. While I drew from these, they seemed to me somewhat self-conscious and guarded. It was the little unsolicited nugget she would threw out at unexpected moments that brought her story to life for me. I recorded these by scribbling on the backs of envelopes and scraps of paper. Of course, each time she repeated a story it was a little different, so whenever possible I tried to view each incident from other angles. When I visited my father in Delhi, we would talk late into the night, with American soap operas flickering in the background on the TV. There were stories, especially about the beauty contest; my mother didn’t want me to tell. Then one day in the mail, I received from her pictures of herself parading in a bathing suit with other international beauties! Giving me, in a sense, permission to share her whole story.

In 1994, my children, then in their teens, were in the audience for my performance at the Chocolate Church Arts Center in Bath, Maine—my younger son Wardreath with a girlfriend in tow. At the end of the performance, Habib, my older son, surprised me by asking if I would come to his college and repeat my performance. He arranged for my fee from various departments of Bates College. Every seat in the Schaeffer Theatre was packed. At my final namaskar, I was stunned by the thunderous applause and standing ovation from the students. I stood on stage feeling like Madonna. Though that was nothing compared to the feeling when Habib stepped on stage and presented me with a bouquet of flowers in full sight of all his peers! I floated off the stage in ecstasy and announced to my husband and children waiting in the wings:

“Guys, that was my last performance, my swan song.”

These voices, these images and the shopping bags bulging with my grandmother’s precious possessions, are my legacies to my children and grandchildren.

Extracted with permission from ‘Dancing in the Family: The Extraordinary Story of the First Family of Indian Dance’, by Sukanya Rehman, published by Speaking Tiger Books