‘India’s frequent attempts to enforce prohibition have been ineffectual’.

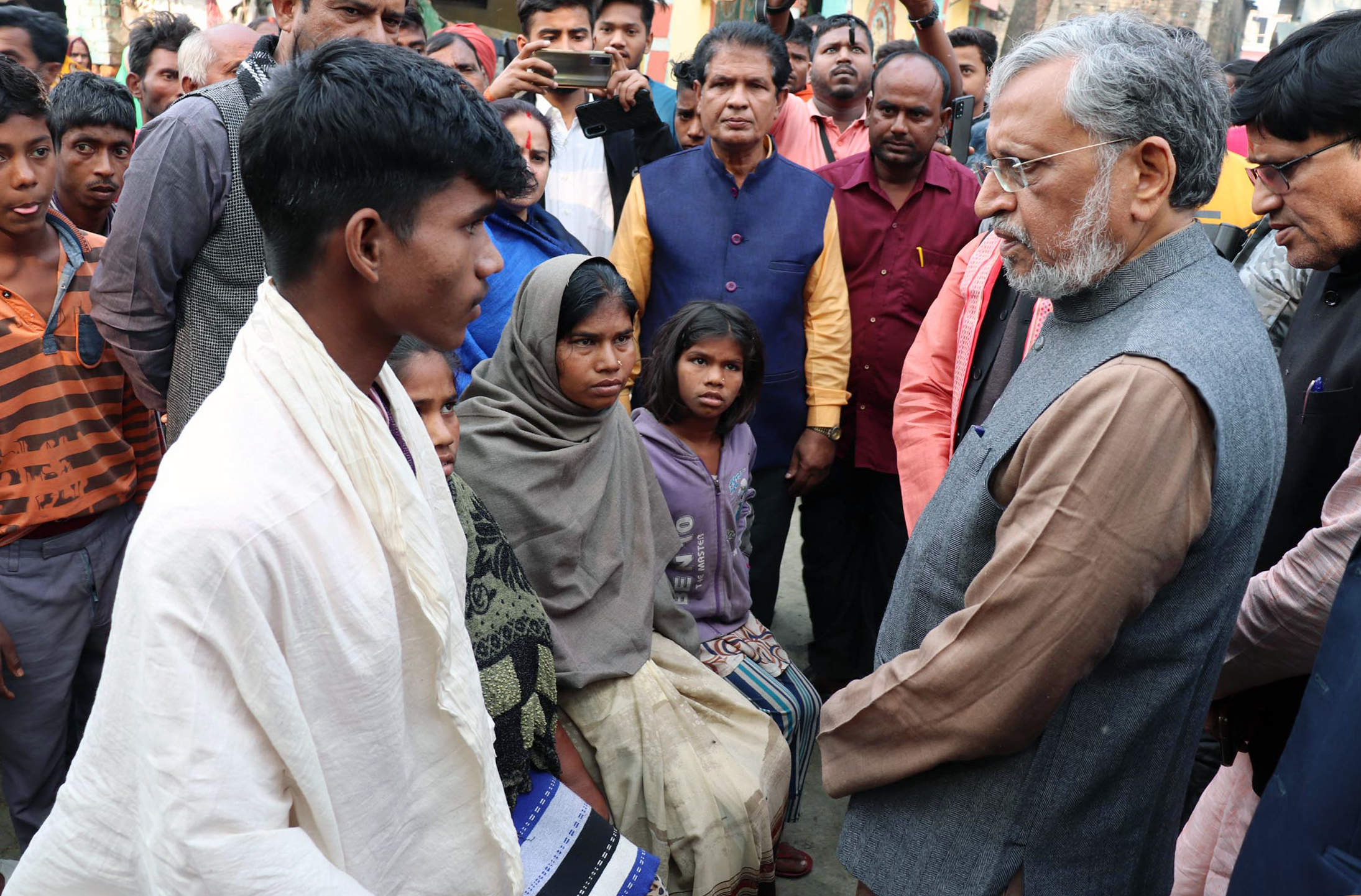

NEW DELHI: Does prohibition really work? The death toll in a suspected hooch tragedy climbed to 70 in dry Bihar in the second week of December, amid the political blame game in the state. The deaths were reported from Saran district, triggering a slugfest in the Bihar Assembly where the ruling “Mahagathbandhan” led by Chief Minister Nitish Kumar and Opposition BJP traded charges over the tragedy.

The sale and consumption of alcohol were completely banned in Bihar by the Nitish Kumar government in April 2016. Kumar said that if “someone consumes spurious liquor, they will die”, as he came under heavy pressure on his alleged failed excise policy. Defending the liquor ban in Bihar, Kumar said that the state’s prohibition policy had benefitted several people and a large number of people have given up drinking alcohol due to his measures.

Former Deputy Chief Minister and earlier close to Nitish Kumar, BJP MP Sushil Kumar Modi, alleged that over 1,000 people lost lives in the state due to spurious liquor after prohibition. However, official figures are 300 hooch-related deaths in Bihar since 2016, around 3.5 lakh cases registered by Bihar police since prohibition imposed, 4 lakh arrested, 40,000 accused in jail and many released through the legal process, interestingly less than 5% conviction rate with police unable to prove most cases. The state’s former Chief Minister Lalu Prasad Yadav was among the most vocal critics. He remarked that he had warned the sitting Chief Minister that he would lose revenue while smugglers would have a field day. The former Chief Justice of India added his strong censure. On 26 December 2021, from a public platform, he berated Bihar’s experiment in prohibition. He dubbed the state’s prohibition law as smacking of a lack of foresight in drafting legislation, the consequence of which was the inundation of courts with liquor-related cases. His annoyance was mainly because of the crippling overburdening of the state’s judicial administration, with lakhs of prohibition cases and bail applications clogging the Patna High Court and the lower courts. Now his party

Bihar imposed complete prohibition in the state in April 2016, drawing its inspiration from Article 47 of the Constitution, which directs the state to endeavour to prohibit consumption of intoxicating drinks and drugs injurious to health. This was also Chief Minister Nitish Kumar’s election promise to the women of the state who have suffered on account of the excessive drinking by their husbands and other male family members. Prohibition laws were made draconian to deal with the issue of alcoholism. Some of the law’s worst features are holding the entire family liable to imprisonment if any family member violated the liquor ban, and imposing a collective fine on a whole village if there was any violation of the prohibition.

It is true that Article 47 of the Constitution obliges the government to prohibit the consumption of alcohol. It is also true that many legal challenges to this constitutional provision have failed. But India’s frequent attempts to enforce prohibition have been ineffectual. Indeed, Article 47 has withered away, and little remains of it in practice other than as parental advice to a prodigal child.

In India, Morarji Desai’s likely well-intentioned but unwise decision to ban alcohol in the Bombay Presidency in the early 1950s was the chief cause of the growth of the smuggling syndicates and the likes of Haji Mastan, Vardarajan Mudaliar, Karim Lala, etc, who were the founding fathers of the Mumbai underworld. In 1977, Prime Minister Morarji Desai told a conference of chief ministers that total prohibition will be enforced throughout the country within four years, that had come as a rude shock to many.

Haryana’s tryst with less than two years of prohibition in the late 1990s adds another chapter to the chequered history of prohibition in India. Delivering on an election promise on the back of the vote of women, the Bansi Lal-led Haryana Vikas Party-Bharatiya Janata Party coalition government imposed prohibition in July 1996.

Exactly 21 months later, it decided to lift prohibition in April 1998, at a political cost, apart from economic and legal ramifications. In this short span, over 90,000 cases were registered for violating prohibition laws. The government blamed five wet states that ringed around the state for the uninterrupted flow of alcohol into the state. At that time, one could spot rows of liquor shops and makeshift bars on the borders of Delhi and Punjab doing whopping business.

Even such harsh laws failed to deter alcohol consumption in the state. Bihar’s location itself made the state vulnerable. The state shares its borders with Nepal, West Bengal, Jharkhand, and Uttar Pradesh. None of these states practice prohibition, and there is evidence that liquor is flowing into Bihar from the neighbouring states, given West Bengal and Jharkhand’s phenomenal rise in excise revenue. Bihar, on the other hand, was losing revenue, and the state’s hospitality and trade sectors were taking a hit. The frustration of the judiciary was writ large in a recent judgment (October 2022) of the Patna High Court. The judge pronounced that the Bihar government had failed to implement prohibition. The state had witnessed many hooch tragedies, putting public life at significant risk. The judge further observed that liquor is freely available in the state, that minors were transporting liquor, and that drug consumption had increased post-liquor ban. Investigating officers deliberately avoided corroborating allegations with evidence, allowing the mafia a free run.

Bihar, already figuring among the fiscally most vulnerable states in the country, chose to forego a large chunk of revenue by imposing prohibition. While no positive consequence has flowed out of prohibition, the policy played its part in further driving the state into penury. For 2015-16, state excise money was estimated at INR 4,000 crore. Over the last seven years since prohibition was imposed, given the usual increment in excise earnings, the state has lost around INR 40,000 crore.

In India, Haryana gave up its attempts at prohibition due to its inability to control illicit distillation and bootlegging. Tamil Nadu and Kerala similarly ventured to ban liquor but abandoned it as they failed at implementation.

Similarly, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, and Manipur overturned prohibition after they failed in execution. Even the state of Gujarat’s prohibition may be a charade, given the supply of liquor from neighbouring Daman, aided by a porous border and administrative complicity.

The most recent experiment was in Maharashtra. The state-imposed prohibition in 2015 in the district of Chandrapur and withdrew it in 2021.

Based on official statistics gathered by government departments, the collector’s report documented the results, which appear to be a replica of the happenings in Bihar. The report declared prohibition in Chandrapur a substantial failure. It noted that the sale of liquor had gone up, and large quantities of illicit and spurious liquor had started circulating via a thriving black market. The state government had lost revenue despite the liquor trade increasing in the district, as revenue from liquor was driven into the black market and private hands. There was a marked increase in the registration of criminal cases and arrests related to prohibition. Especially worrying was the growing involvement of women and children in the illicit liquor trade.

The writer is Editorial Director ITV network-India News & Dainik Aaj Samaj.