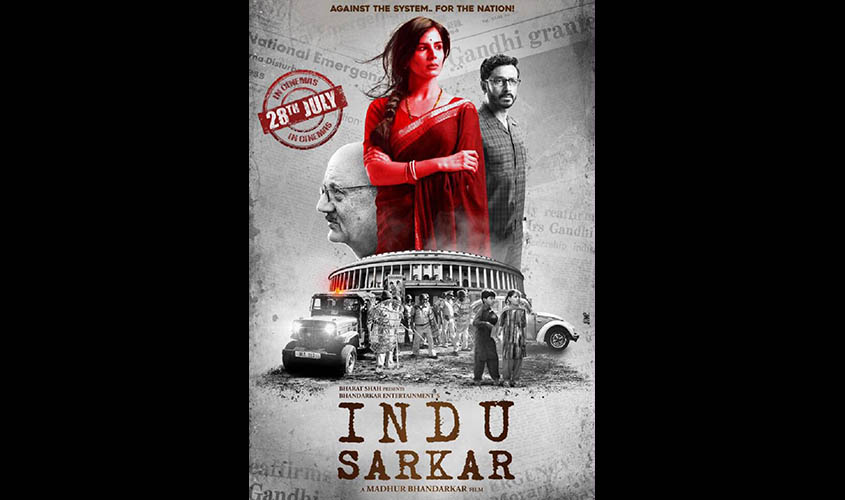

In a country where over 70% of the population is under the age of 40 years, the recollection of the terrible Emergency, which occurred more than four decades ago, is nearly a fogged-out fact. Therefore, Madhur Bhandarkar’s film Indu Sarkar is unlikely to have the desired impact. The current generation is oblivious even of contemporary history, and hence any attempt to recall events of those dreaded days would fall on deaf ears. Today’s cine-goer would be more comfortable in relating to the fear-factor, if at all it presently exists, and affects his day to day life.

In a country where over 70% of the population is under the age of 40 years, the recollection of the terrible Emergency, which occurred more than four decades ago, is nearly a fogged-out fact. Therefore, Madhur Bhandarkar’s film Indu Sarkar is unlikely to have the desired impact. The current generation is oblivious even of contemporary history, and hence any attempt to recall events of those dreaded days would fall on deaf ears. Today’s cine-goer would be more comfortable in relating to the fear-factor, if at all it presently exists, and affects his day to day life.

The Congress party has every reason to be repentant of the Emergency, which lasted for a period of nearly 20 months, and led to its first major debacle in the electoral arena, where even a powerful Prime Minister like Indira Gandhi and her younger son, Sanjay, lost to their opponents Raj Narain and Ravindra Pratap Singh in the Rae Bareli and Amethi constituencies, respectively. There is no way one can endorse the proclamation, which led to the suspension of the fundamental rights of individuals and the arrest of scores of politicians, including many who today occupy pivotal positions.

Therefore, it was pointless for anyone in the present Congress, which has no resemblance to its earlier avatar, to protest against the screening of the film, however exaggerated and removed from the truth it may seem to some of the leaders. Bhandarkar is a seasoned filmmaker and thus has the creative licence to showcase his interpretation of the dark days, even if there is 70% element of fiction in the celluloid depiction of the episodes.

Indira Gandhi had the humility to accept that she had erred in clamping down an Emergency. In 1978, during her first trip to London post-Emergency, a hostile press awaited her arrival at the Heathrow airport. The first question put forward by a correspondent was laced with sarcasm. She was asked to spell out the gains of the Emergency. Unruffled by the loaded query, Indira Gandhi looked straight in the eye of the journalist and stated in an even-key voice that during the period, her party had managed to alienate every section of society in the country. In a single stroke, she had silenced her critics with her witty and truthful response. The viciousness in the air evaporated, and the former Prime Minister emerged victorious in her first major brush with the international media, post Emergency.

The Emergency is remembered for the excesses on the common people, most notably those connected with the sterilisation drive. Any person who offered himself for a vasectomy operation was gifted, as an incentive, a transistor set or a five kilogram tin of vanaspati oil (Dalda or Rath). Yes, there were cases of forced sterilisation, but in a country where the bureaucracy’s favourite pastime is to fudge figures to impress their political masters, the official claims could have been doubtful. Thus the inflated statistics went far in generating the fear-factor.

Old timers would remember that shortly after the Emergency was lifted, there were four persons who emerged as the chief villains, and were described as Indira’s caucus or gang of four: Sanjay Gandhi, former Haryana Chief Minister Bansi Lal, former Information and Broadcasting Minister Vidya Charan Shukla and the former Minister of State for Home Om Mehta. The Bharatiya Jana Sangh and subsequently the Janata Party and the BJP went overboard to hold them responsible for the excesses.

The supreme irony is that Sanjay’s widow, Maneka and son, Feroze Varun, both are BJP MPs. True, the two were not at fault, but by accepting them in its ranks, the BJP, has also to some degree, reconciled with Sanjay’s legacy; Bansi Lal, who had formed his Haryana Vikas Party, aligned with the BJP and ruled as the Chief Minister of the state. V.C. Shukla, too, did a short stint with the BJP, before returning to the Congress. Om Mehta faded away into oblivion.

Bhandarkar’s film vividly depicts the demolitions at the Turkman Gate in Central Delhi. Civil servant turned politician, Jagmohan was at one time accused of being responsible for the demolitions when he was the vice chairman of the Delhi Development Authority (DDA). He was also sought to be prosecuted during the hearings of the Shah Commission. Subsequently, he joined the BJP and was elected thrice on its ticket from the New Delhi constituency. He remained a Central minister in the A.B. Vajpayee government after his stint as the Governor of Jammu and Kashmir.

The short point is that the BJP and the RSS, which opposed the Emergency, compromised on their stance, and did business with those who were at one time on the other side of the fence. Bhandarkar’s film is merely a celluloid version of those bygone days and hence, should be seen in this light. It is not a recollection of history, but a presentation of some facts that tend to take matters in one direction.

Therefore, anyone who is trying to be self-righteous about what happened during the Emergency should also look at its aftermath and how “certain villains of one era were resurrected in another”. The Emergency will always remain a blot on our otherwise vibrant democracy. The Congress has paid for its transgressions, but the BJP cannot gloat and continue to sit in perennial judgement. As is well documented, people in glasshouses should not throw stones at others. Between us.