Bangladeshi photographer Shahidul Alam’s images are not conventional representations of suffering and resistance. He is trying to break through the clichés that have a deadening effect on our eyes in a photo-saturated world, writes Arthur Lubow.

Like Woody Guthrie, who called his guitar an anti-fascist weapon, Bangladeshi photographer Shahidul Alam has used his camera for 35 years as a tool to advance social justice. He began by documenting street protests in Dhaka, the capital, in the mid-1980s, making pictures in the tradition of the Magnum photographers, especially Henri Cartier-Bresson. But over time, he pushed against the natural constraints of a medium that registers what is seen, so that he might illuminate what is suppressed or has vanished.

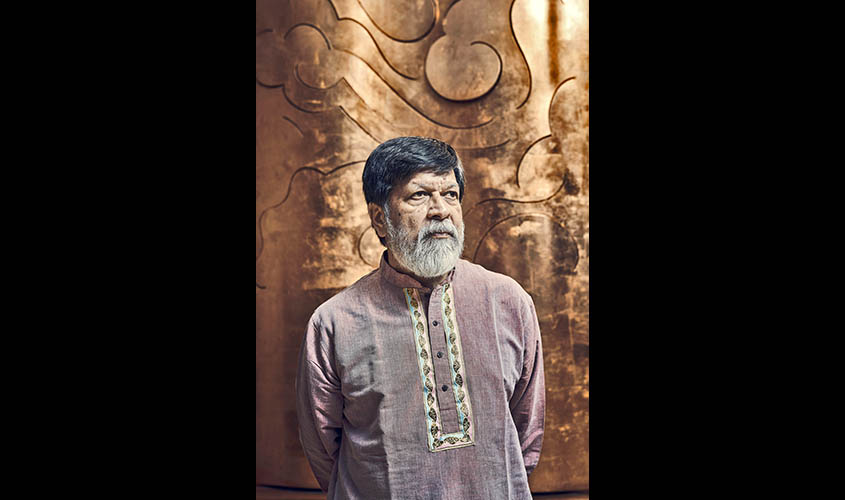

“There is a wall in our flat with pictures of friends of ours who have disappeared or been killed,” said Alam, 64, who was visiting New York from Dhaka recently for the opening of Truth to Power, his first retrospective in the United States, at the Rubin Museum of Art, through May 4. “Every so often we add a picture.”

But how does a photographer portray people who have disappeared with hardly a trace? That question, which Alam addresses creatively in works in this show, ratcheted up to a frightening level last year, when he was arrested and jailed after criticising the government’s violent response to student demonstrations. “I’ve been photographing the missing and now even the camera was missing,” he said.

Included in the Rubin exhibition is a white 3D model, never before displayed, that Alam’s niece, architect Sofia Karim, constructed—based on his memories—of the Keraniganj prison on the city outskirts, to which he was brought, handcuffed and blindfolded, on Aug. 5, 2018. The police had found him alone in his apartment at about 10:30 that night. Before being pushed into a car, he resisted as long and as loudly as he could, to insure that his neighbors would know what had happened. “When I got picked up, I didn’t know if I would live or die,” he said.

Oddly, it wasn’t his photographs that precipitated the arrest but an interview he gave to Al-Jazeera, praising student

Far from being an anonymous detainee, Alam was an internationally known figure. He is an affable man who smiles readily, listens empathetically, speaks with long, engaging digressions that invariably circle around to arrive at a sharp point, and enjoys close friendships with many people around the world.

Aside from his own photography, in 1989 he founded—with his life partner, Rahnuma Ahmed, a journalist and human rights activist—the Drik Picture Library, a multifunction agency in Dhaka that provides clients with photographers and printing services. It also features an exhibition gallery. In addition, he established the Pathshala South Asian Media Institute and other programs to train local photographers. Raising the global profile of Drik, he staged, in December 2000, the first Chobi Mela, a biennial photography congress in Dhaka that is now the largest in Asia and attracts photographers internationally.

Still, he readily acknowledges that in his poverty-stricken homeland, he is a privileged person. Born to middle-class parents in Dhaka, Alam was 15 in 1971, when a civil war broke out and culminated in the independence of Bangladesh from Pakistan. Two years later he moved to Liverpool, England, where his sister was a doctor, and prepared for a career as a research scientist. He went on to earn a Ph.D. in chemistry from the University of London, but at the same time, he was becoming enthralled with photography and began moonlighting as a child portraitist.

Photographing children required him to win over their parents and to put his subjects at ease. “Taking pretty pictures is easy,” he remarked. “Understanding the human fabric and developing a position of trust is the important skill.”

Increasingly active in social-justice campaigns, he worried that the success of his business, which was taking off and bringing about $500 a week, might make him complacent. His ambitions lay elsewhere. “I got involved with the Socialist Workers Party in London and saw how the movement used the power of images,” he said. “I realised it was a good tool.”

In 1984, he moved back to Dhaka to work as a professional photographer. At first he relied on fashion and advertising jobs, but in time he devoted himself fully to photojournalism. His photographs of street protests against the autocratic ruler, President Hussain Muhammad Ershad, are strong. Even more memorable are his pictures, such as one of an elderly woman cooking on the roof of her flooded house, that portray the aftermath of a catastrophic cyclone in 1988. A later photograph in the same spirit shows a cow walking a narrow spit of dry ground in search of grassland, amid former pasture that has been flooded for shrimp aquaculture. Seen today, these photographs of resilience in the face of devastation within the low-lying, river-permeated country seem prophetic of the calamitous effects of climate change and environmental degradation.

Alam maintains that his photographs differ from those of Western photojournalists. “The photographers in the West were photographing someone else’s struggle,” he said. “I was an activist taking photographs of my own movement. The political stories I was trying to tell are much more complex than the tightly packaged stories of Western photographers. Class issues, issues of religion, environmental issues, are all part of it.” Furthermore, he argues, people respond differently to a local photographer. “They see me as one of them,” he said.

Since 2011, Alam has been pursuing the tragic case of Kalpana Chakma, a young activist for the rights of women and the indigenous Pahari people of the Chittagong Hill Tracts in southeastern Bangladesh, who disappeared after her abduction by an army lieutenant in June 1996. Because few photographs or possessions of Chakma survive, Alam conducted what he calls a “photo-forensic study,” making colour pictures of traces, real or imagined: her mud-crusted slipper found near the pond where she was last seen, a bit of bamboo and string from her bare room, close-ups of the fabrics of her few garments. “You would have asked witnesses to the scene, but that was never done,” he explained. “So I asked the silent witnesses.” Some pictures are semiabstract, like a red dress that appears to fold around a ghostly body.

He also took advantage of his scientific background. Adapting the laser device that is used in clothing factories in Bangladesh to distress denim jeans, he burned portraits of the human rights activists promoting her cause onto simple straw mats, the sort used for sleeping by poor Bangladeshis, including Chakma. In the exhibition, the suspended charred mats are ringed by votive candles, which together evoke, for an informed viewer, the fires that government-backed Bengali settlers put to Pahari homes.

Alam’s images are not conventional representations of suffering and resistance. He is trying to break through the clichés that deaden our eyes in a photo-saturated world.

“There are pictures photographers and their editors might go to when trying to depict a crisis, because it is what people have learned to understand—this is what famine looks like, this is what natural disaster looks like,” said Lauren Walsh, director of the Gallatin Photojournalism Lab at New York University and the author of the recent book, “Conversations on Conflict Photography.” Especially in the photographs of what has gone missing, Alam counters that trend. As Walsh put it, “Shahidul is really asking you to stop and consider.”

© 2019 The New York Times